Understanding Tolkien: Why His Landscapes Work

There’s no better way to experience the distinction between text and structure than to go back to the roots of our genre.

A few years ago, as a result of a spectacular parenting own-goal, The Hobbit -– a battered old copy that Mrs Harold-Page’s father once purchased for 8s 6d –- ended up as our five year old son’s bedtime story.

It was near midnight, and we were trying to coax our overtired insomniac little boy into sleep mode. I thought, Let’s read something that will hold his attention, but be so far over his head as to hypnotise him into dozing off. Instead, of course, the little blighter perked up and asked enough questions to understand what was going on. The following night — at a more reasonable time — he wanted The Hobbit again. I pointed out it was a bit old for him. Could he even remember the last thing that happened?

They got captured by trolls, but Gandalf did this voice then another voice and the trolls argued until the sun came up and they turned to stone…Is that Smaug on the cover, Daddy?

So, The Hobbit it was.

Reading the Hobbit is a bit like listening to Bill Haley and the Comets. The beat is there, but the delivery — though charming and skilled — is not quite right to the modern taste.

The Hobbit is packed with Herodotian ring composition, editorializing, explicit allusions to the character’s future, and lots of “telling” rather than “showing,” all of which distance us from the story.

Worse, Gandalf is the only person who really does anything until well into the book. It’s page 62 before Thorin even strikes a goblin, and he does that off screen, and in narrative summary — imagine how Robert E Howard would have handled that…

Even so, the story and the world it articulates, rocks.

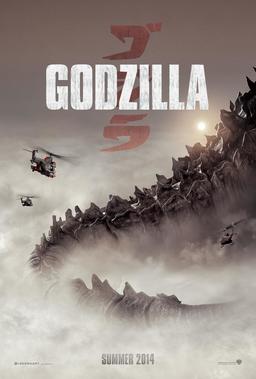

THE TRAILER IS HERE AND YOU SHOULD BE WATCHING IT.

THE TRAILER IS HERE AND YOU SHOULD BE WATCHING IT.