Steven Brust’s Jhegaala

Jhegaala

Jhegaala

Steven Brust

Tor (300 pages, $24.95, July 2008)

Reviewed by Bill Ward

The world of epic fantasy has its Martins, Jordans, and Eriksons, writers at the helm of long-running series with massively convoluted plots and hundreds of characters — and, quite often, no end in sight. But when compared to Steven Brust’s Taltos novels, which debuted in 1983, these long-running epics are Johnny-come-latelys, part of a newer way of packaging fantasy fiction that began with Robert Jordan in the early nineties and shows no signs of abating. Jhegaala is the eleventh book chronicling the adventures of the clever and cynical rogue Vlad Taltos, a character whom Brust has been writing about for twenty-five years in a series that hearkens back to an earlier mode of serial fantasy, the episodic sword and sorcery tale.

Which means, unlike with epic fantasy, a reader can pick up a book in the middle of Brust’s series and not have to worry about needing a wealth of prior plot and exposition to understand it. Jhegaala is perhaps an even better example of this than some of Brust’s prior books, as it takes place completely out-of-context chronologically and geographically with the rest of the series. Vlad, on the run from his own House and exiled from his home city of Adrilankha, travels to his ancestral homeland in the East. There, among his own kind in the town of Burz, he stumbles into the paranoid world of local powers, and begins to unravel a mystery that involves a pervasive guild, a coven of witches, and the ruler of the region himself.

I am going to semi-repeat myself in my next two Black Gate posts, going over graphic novel versions of material that I’ve discussed over the past few months.

I am going to semi-repeat myself in my next two Black Gate posts, going over graphic novel versions of material that I’ve discussed over the past few months. Conan the Hunter

Conan the Hunter If there is a watch, then there must be a watchmaker. That’s the crux of the argument for intelligent design, that existence, and specifically you and me, are the result of some conscious creator. My main problem with this is the adjective “intelligent.” If I was designing existence, there’s a lot I’d leave out, like cancer or maggots or flatulence or Glenn Beck. Or that for certain kinds of life to continue and thrive, other life forms must suffer. Besides, this all begs the question of, if there is a designer (intelligent or otherwise), who created the designer?

If there is a watch, then there must be a watchmaker. That’s the crux of the argument for intelligent design, that existence, and specifically you and me, are the result of some conscious creator. My main problem with this is the adjective “intelligent.” If I was designing existence, there’s a lot I’d leave out, like cancer or maggots or flatulence or Glenn Beck. Or that for certain kinds of life to continue and thrive, other life forms must suffer. Besides, this all begs the question of, if there is a designer (intelligent or otherwise), who created the designer? While her work sometimes hints at the fantastic, Lydia Millet isn’t strictly speaking a fantasy writer, certainly not in the sense of questing elves or weird alternate universes, and certainly not as evidenced in her new short story collection, Love in Infant Monkeys. Yet Millet’s work is frequently mentioned in genre venues; indeed, one of the stories collected here, “Thomas Edison and Vasil Golakov,” (in which the famed inventor of light bulbs and power generation attains metaphysical illumination by continually re-running a film of a circus elephant’s seemingly Christ-like electrocution)previously appeared in

While her work sometimes hints at the fantastic, Lydia Millet isn’t strictly speaking a fantasy writer, certainly not in the sense of questing elves or weird alternate universes, and certainly not as evidenced in her new short story collection, Love in Infant Monkeys. Yet Millet’s work is frequently mentioned in genre venues; indeed, one of the stories collected here, “Thomas Edison and Vasil Golakov,” (in which the famed inventor of light bulbs and power generation attains metaphysical illumination by continually re-running a film of a circus elephant’s seemingly Christ-like electrocution)previously appeared in  For this edition of my irregular review of the latest (more or less) short fiction, I thought I’d try something a little different. Usually I try to focus on the stories that worked the most for me, with maybe some attention on those that didn’t and why; at the same time, I also try to convey a flavor of everything else, if only just to alert you that an author is in the publication without, for any number of reasons, wanting to get into discussing the story to any great length. Note the use of the word “try.” One of the challenges here is to provide some substantive, possibly even useful, discussion to an audience that I’m assuming hasn’t already read the material. As

For this edition of my irregular review of the latest (more or less) short fiction, I thought I’d try something a little different. Usually I try to focus on the stories that worked the most for me, with maybe some attention on those that didn’t and why; at the same time, I also try to convey a flavor of everything else, if only just to alert you that an author is in the publication without, for any number of reasons, wanting to get into discussing the story to any great length. Note the use of the word “try.” One of the challenges here is to provide some substantive, possibly even useful, discussion to an audience that I’m assuming hasn’t already read the material. As

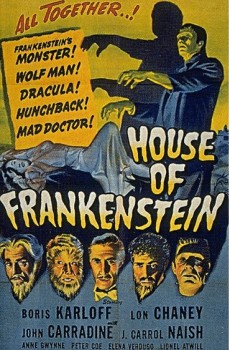

House of Frankenstein (1944)

House of Frankenstein (1944) Fans of Tom Waits are often divided into two camps: those who favor the early boozy Kerouac, be-bop inspired crooner of life’s derelicts and losers up until he transmogrified beginning with the “Heartattack and Vine” album and “crossed over” into Kurt Weill cacaphonous orator of the absurd; fans of the later period sometimes disdain the earlier, and vice versa, despite the obvious connections. Me, I’m in the third camp as a huge admirer of both milieus. (I suppose there’s a further quarter of people who can’t stand Waits at all, but, much like the folks who still tiresomely maintain Dylan hasn’t done anything since his protest days, aren’t worth serious attention.)

Fans of Tom Waits are often divided into two camps: those who favor the early boozy Kerouac, be-bop inspired crooner of life’s derelicts and losers up until he transmogrified beginning with the “Heartattack and Vine” album and “crossed over” into Kurt Weill cacaphonous orator of the absurd; fans of the later period sometimes disdain the earlier, and vice versa, despite the obvious connections. Me, I’m in the third camp as a huge admirer of both milieus. (I suppose there’s a further quarter of people who can’t stand Waits at all, but, much like the folks who still tiresomely maintain Dylan hasn’t done anything since his protest days, aren’t worth serious attention.)