A Slayer of Monsters: Beowulf translated by Howell D. Chickering, Jr.

In high school I read Beowulf on my own. It was from the Folio Society, illustrated by Virgil Burnett and translated by Kevin Crossley-Holland. Some years later I read John Gardner’s Grendel, a commentary on humanity and Jean-Paul Sartre more than on Beowulf itself. Eventually I came across Michael Crichton’s Eaters of the Dead, a mashup of the journal of Ahmad ibn Fadlan and Beowulf (and reviewed by me here). Since it’s been ages since I read the original poem, I thought I should give it a go and find something interesting to say. I’m struggling, but bear with me as I try.

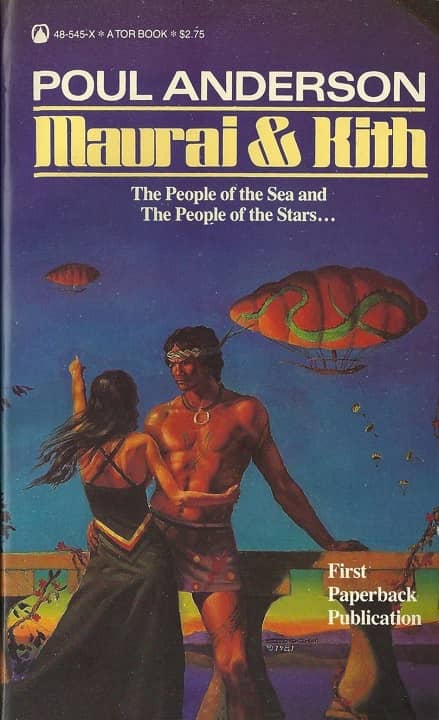

Beowulf is a heroic tale set in 6th century Scandinavia. Scholars debate whether it existed first as an oral tale from pagan days, only to be written down in later Christian times, or if it is a mix of Germanic oral tradition and literate Anglo-Saxon poetry, or something else altogether. The sole extant version of it is written in Old English, the language of Anglo-Saxon England (people originally from Northern Germany and Southern Denmark), and preserved as part of the Nowell Codex, a manuscript written between the end of the 10th and beginning of the 11th centuries. Several characters mentioned in Beowulf make appearances in other Nordic tales, particularly the Hrólfs saga kraka (The Saga of King Rolf Hraki. My review of Poul Anderson’s telling of the saga is here).

Here’s Wikipedia describing the technical aspects of the poem:

Anglo-Saxon poetry is constructed very differently from a modern poem. There is little use of rhyme and no fixed number of beats or syllables; the verse is alliterative, meaning that each line is in two halves, separated by a caesura, and linked by the presence of stressed syllables with similar sounds. The poet often used formulaic phrases for half-lines, including kennings, evocative poetic descriptions compressed into a single compound word.

Having neither Old English nor expertise in epic German or Anglo-Saxon poetry, I won’t weigh in on the matter of Beowulf‘s origin. Suffice to say it is a very old poem that not only recounts Beowulf’s exploits, but also provides partial histories of several Scandinavian royal households, describes battles, and gives an idea of life in ancient Scandinavia.

…