A Slayer of Monsters: Beowulf translated by Howell D. Chickering, Jr.

In high school I read Beowulf on my own. It was from the Folio Society, illustrated by Virgil Burnett and translated by Kevin Crossley-Holland. Some years later I read John Gardner’s Grendel, a commentary on humanity and Jean-Paul Sartre more than on Beowulf itself. Eventually I came across Michael Crichton’s Eaters of the Dead, a mashup of the journal of Ahmad ibn Fadlan and Beowulf (and reviewed by me here). Since it’s been ages since I read the original poem, I thought I should give it a go and find something interesting to say. I’m struggling, but bear with me as I try.

Beowulf is a heroic tale set in 6th century Scandinavia. Scholars debate whether it existed first as an oral tale from pagan days, only to be written down in later Christian times, or if it is a mix of Germanic oral tradition and literate Anglo-Saxon poetry, or something else altogether. The sole extant version of it is written in Old English, the language of Anglo-Saxon England (people originally from Northern Germany and Southern Denmark), and preserved as part of the Nowell Codex, a manuscript written between the end of the 10th and beginning of the 11th centuries. Several characters mentioned in Beowulf make appearances in other Nordic tales, particularly the Hrólfs saga kraka (The Saga of King Rolf Hraki. My review of Poul Anderson’s telling of the saga is here).

Here’s Wikipedia describing the technical aspects of the poem:

Anglo-Saxon poetry is constructed very differently from a modern poem. There is little use of rhyme and no fixed number of beats or syllables; the verse is alliterative, meaning that each line is in two halves, separated by a caesura, and linked by the presence of stressed syllables with similar sounds. The poet often used formulaic phrases for half-lines, including kennings, evocative poetic descriptions compressed into a single compound word.

Having neither Old English nor expertise in epic German or Anglo-Saxon poetry, I won’t weigh in on the matter of Beowulf‘s origin. Suffice to say it is a very old poem that not only recounts Beowulf’s exploits, but also provides partial histories of several Scandinavian royal households, describes battles, and gives an idea of life in ancient Scandinavia.

Hwæt! We Gar-Dena in geardagum, Listen! We have heard of the glory of the Spear-Danes

þeod-cyninga, þrym gefrunon, in the old days, the kings of tribes --

hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon! how noble princes showed great courage!

Beowulf, lines 1-3

From those opening lines, the poet makes clear we will be looking back on a heroic past when kings were bold and brave, and perhaps implies that that is no longer the case. In those days long gone, Shield Sheafson, a terror to his enemies, became king of the Danes. His son Beow was a smart and noble king, as was his grandson, Halfdane, and his great-grandson, Hrothgar. In the latter days of his long, successful reign, Hrothgar built a great hall, Heorot, and from his throne there, handed out great gifts to his followers. These glorious days come to a bloody end when the monster Grendel, lurking in the night, makes its appearance.

ða se ellen-gæst earfoðlice Then the great monster in the outer darkness þrage geþolode, se þe in þystrum bad, suffered fierce pain, for each new day þæt he dogora gehwam dream gehyrde he heard happy laughter loud in the hall, hludne in healle; Beowulf, lines 86-88

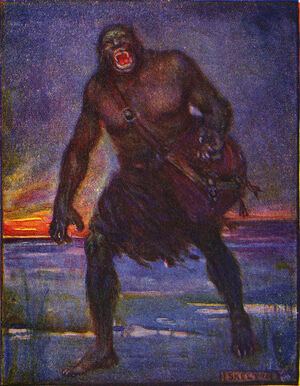

Grendel begins to terrorize the inhabitants of Heorot. Each night he creeps into the great king’s hall and steals away with dozens of his men, then returns to his lair and devours them. Soon, the Danes are forced to abandon Heorot in the face of the monster’s depredations. Only when the Geatish (Southern present-day Sweden) warrior, Beowulf, and his band of men arrive is there a sense of hope.

Beowulf is all the things a hero and warlord should be. His uncle is the king of the Geats, and Beowulf has built a mighty reputation. He is strong and brave, quick-witted, loyal to his lord, and rewards his followers generously. Later in life, despite being warned against the diminishment of strength brought on by age and hubris, he will fatally seek to defend his own land from a dragon. But in his youth, he is everything a hero needs to be.

My teenage reaction on reading Beowulf was that it seemed somewhat different than much of the other Germanic legends I’d encountered. Hrothgar wasn’t cursed for some past sin, just beset by a vile descendant of Cain. Beowulf is noble and true, bearing no obvious flaws or past sins. In his battles against Grendel, Grendel’s mother, and even the dragon which ultimately killed him, Beowulf was victorious. The battles against the monsters were gory and exciting. Already an inveterate reader of fantasy, it was right up my alley. There seemed little of the doom and murderousness that suffused other tales; it was just a cool story. Rereading it now, I can only offer up my youthfulness as an excuse for having missed the deeply mournful nature of Beowulf. J.R.R. Tolkien, the founder of modern scholarship about the poem, considered it a lament for the doomed nature of a man and his achievements. I’m sure there’s more to it than that, but that seems on target.

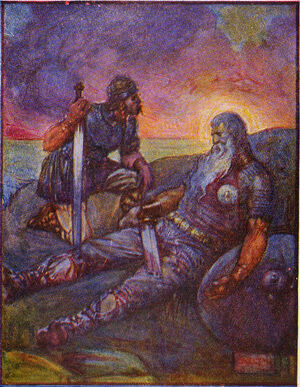

The first intimations of the hero’s fate come in Hrothgar’s admonitions to the young fighter. Hrothgar is smart enough to know he is too infirm to face Grendel and is able to restrain his pride and allow someone more capable to do so. Despite his early counsel, when Beowulf’s time comes he goes forth with few men to face the dragon. Before coming face to face with his adversary — and before most of his men flee in terror — Beowulf reflects on past events, sensing his own fate is at hand. As he recalls his kingdom’s recent history of battle and kin-killing, he imagines a father mourning his executed son. It is one of the most despair-filled things I have ever read.

Swa bið geomorlic gomelum ceorle "So it is bitter for an old man to gebidanne, þæt his byre ride to have seen his son go riding high, giong on galgan, þonne he gyd wrece, young on the gallows; then may he tell sarigne sang, þonne his sunu hangað a true sorrow-song, when his son swings, hrefne to hroðre, ond he him helpe ne mæg, a joy to the raven, and old and wise eald ond infrod, ænige gefremman. and sad, he cannot help him at all. Symble bið gemyndgad morna gehwylce Always, each morning, he remembers well eaforan ellorsið; oðres ne gymeð his son's passing; he does not care to gebidanne burgum in innan to wait for another guardian of heirlooms yrfeweardas, þonne se an hafað to grow in his homestead, when the first has had þurh deaðes nyd dæda gefondad. such a deadly fill of violent deeds. Gesyhð sorhcearig on his suna bure Miserable, he looks upon his son's dwelling, winsele westne, windge reste deserted wine-hall, wind-swept bedding, reote berofene. Ridend swefað, emptied of joy. The ride sleeps, hæleð in hoðman; nis þær hearpan sweg, warrior in grave; no harp music gomen in geardum, swylce ðær iu wæron. no games in the courtyard, as once before. Beowulf, lines 2444-2459

Upon his death, Beowulf’s men immediately fear for the future. As England after Arthur, Geatland’s peaceful age seems doomed without its exemplary king and protector. Enmity between the Geats and Swedes is great, the Swedish king, Ongentheow, having been killed years before by Geatish soldiers. Now, with mighty Beowulf dead and without an heir, the Swedes are sure to seek revenge. The Franks and Frisians are also bound to smell blood in the water and threaten Geatland as well.

Then, in a final, posthumous blow to Beowulf, his nephew, Wiglaf, the one retainer who stayed by his side when the dragon appeared, delivers a remonstration on his king’s last act. No matter how well warned he’d been by Hrothgar, even the great Beowulf succumbs to pride in the end. Still chasing heroic deeds, he sacrifices his kingdom’s safety for his own glory.

"Oft sceall eorl monig anes willan "Often many earls must suffer misery wræc adreogan, swa us geworden is. through the will of one, as we do now. Ne meahton we gelæran leofne þeoden, We could not persuade our beloved leader, rices hyrde, ræd ænigne, our kingdom's shepherd, by any counsel, þæt he ne grette goldweard þone, not to attack that gold-keeper, lete hyne licgean þær he longe wæs, to let him lie where long he had lain, wicum wunian oð woruldende; dwelling in his cave till the end of the world. heold on heahgesceap. He held to his fate. Beowulf, lines 3077-3084

I was a reader of Norse myths as a kid and had already read Tolkien twice when I first read Beowulf, but I was not as deeply aware of or enchanted by “the whole Northern thing,” to quote W.H. Auden, poet and student of Tolkien. Broadly speaking, it refers to the Germanic understanding that while everything and everybody — the gods included — were doomed, it was incumbent on humans to be courageous in the face of darkness. Beowulf’s doom, though decades away, ultimately renders all his triumphs moot. Even his liberation of Denmark from Grendel is wrought meaningless in the end. From other sources, we learn Hrothulf, Hrothgar’s nephew, will kill his cousins and seize the throne for himself. Doom runs through Beowulf; not always out in the open, but always there.

It’s hard to believe that having already read The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, as a teenager reading Beowulf I didn’t notice all the bits and pieces lifted by Prof. Tolkien for his stories. The name of Beorn the were-bear is inspired by our hero. There is much debate over the meaning of Beowulf’s name, though the most commonly accepted theory is that it means “bee-wolf,” a kenning for bear. Many ancients used such devices to name bears, believing if you called the animal by its actual name it would appear. Beowulf is also thought to be an earlier version of the hero Bödvar Bjarki, a man cursed to take on a bear’s form at times. Beowulf’s dragon is clearly a template for Tolkien’s Smaug. It is serpentine and sleeps atop a vast pile of treasure such that it encrusts its chest. Like Smaug, its fury is aroused by the burglary of one small goblet by a thief, though not a hobbit.

One of the most important things Tolkien introduced to the study of Beowulf was taking it seriously as a work of art. Many earlier scholars had preferred to look at it for depictions of ancient Scandinavia and bemoaned the presence of monsters, as that supposedly rendered it less serious. Again, without a leg to stand on academically, I find myself on the professor’s side. It is a deeply affecting poem, filled with moments of great insight and pathos. In Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics (1936), the groundbreaking collection of his lectures on the subject, he described it as being about “man at war with the hostile world, and his inevitable overthrow in Time.” There is so much to reflect on and ponder in this tale that I am clearly not finished with it.

In fact, now I want to buy Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary (2015). It contains Tolkien’s personal translation of the poem. While he never intended for it to be published, the book includes the original commentary that led to The Monster and the Critics, along with other works by Tolkein regarding Beowulf. I’ve also got Seamus Heaney’s popular translation. While I’ve read some serious criticism about it, Heaney’s translation is clearly an easier read than the one by Howell D. Chickering. I also want to go back to John Gardner’s Grendel. While its concerns range far beyond commenting on the original poem, it seems like something I should do.

Fantasy, particularly sword & sorcery, is rooted in myth and legend. In its formative years, it drew most heavily on the Germanic legendarium. Beowulf, as one of the finest surviving examples of this body of legend, can’t help but have been influential on the genre’s development. The examples of Tolkien’s borrowings are just the most obvious. If you haven’t read it yet, do so.

P.S. The monster fights are still really cool.

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

I haven’t read any of the translations of the poem, but I enjoyed Tolkien’s prose translation.

It seems pretty clear that the Christian scribe changed some of the “problematic” words (like names of pagan gods, even if the characters themselves are clearly pagan and not Christians), just like zealous people today edit or censor older works that have “problematic” words.

So in the end it becomes difficult to know what is the work of the original author and what is the work of editors and censors, something I for one find more problematic.

But OTOH it may give the works something of an aura of mystery. After all, Tolkien was drawn to the “Dark Ages” of the North Sea region, precisely because so much of its history are legends shrouded in darkness, with gaps to fill.

I wasn’t aware that Heaney’s translation has been criticized. Is there a way to briefly summarize the comments of critics?

Primarily, he used numerous words distinct to his rural Irish upbring that some feel detracts from the poem’s Anglo-Saxon history. He’s also more colloquial and adheres less to the literal meaning of the poem than many others, largely in the name of poetry and accessibility.

I too also read Beowulf in high school. I read it when I was suppose to be studying Spanish.

Disputes between translators about translations can only be judged by someone who knows the original language in question, i.e. someone who doesn’t need to read a translation.

But Howell D. Chickering, Jr. is a pillage-and-plunder Viking name if I’ve ever heard one.

Here’s a confession – I have read Beowulf in the original Old English and translated it. Back in the 70s, when I was doing my English degree, I was given the option of studying Old English and Old Icelandic. I am probably still the only student at my particular college, Goldsmiths’ in London, to have ever done Old Icelandic. Not really being very good at these languages and, surprisingly, not finding a job which would pay me to use them, my skills have become rusty and I now read these texts in translation. With regard to the Heaney translation, it may not be linguistically accurate but it certainly conveys the linguistic “feel” of the poem. I have not come across the Chickering translation before but it certainly seems to be close and fluid. Too many translations are stiff and too many translators are not taken with the contents of the poem, so their translations come out as flat. Over the years, I have read a great deal of essays on the poem which emphasise either its pagan roots or its Christianity. Being atheistic myself, Beowulf strikes me as being a deeply Christian poem and a very moving one. Some critics expound the theory that Beowulf is a Christ figure, a warrior who fights the descendants of Cain for the glory of God. I would not go that far but the poem does seem to me to be suffused with Christian belief. The final image is of a memorial to the dead hero, a mound on a headland in which is buried the treasure of the dragon – “a marker that sailors could see from afar”. Round this mound process his warrior companions who extol his deed and exploits. All very heroic and pagan but the sea has long been a metaphor for the unknown and Beowulf’s mound is a beacon against the darkness of the sea and symbol of hope for those who travel across the unknown. As you can imagine, Beowulf can get right under the skin of even the most confirmed atheist.

I also fell in love with this poem at an early age. It is astonishing and heartening that this classic continues to draw readers . This post made my day.

I remember reading the Sutcliffe version when I was a kid – which was pretty good as I recall.

In terms of the Christian influence, the old Irish epic – The Tain – suffers from similar problems in that you have a much older work filtered through a Christian sensibility, mainly because the person usually transcribing it to paper was a monk. So the Tain ends up as a cautionary tale about what happens if you cut a woman too much slack (she gets too big for her boots, bosses her husband around, starts a war etc, etc) plus there’s a lot of laboured symbolism which I very much doubt was a feature of the original.

And there is also the newest translation, by Maria Dahvana Headley, who followed up her modern prose re-telling that focused on Grendel’s mother (The Mere Wife), with a translation of Beowulf, one that takes the mysterious call for attention “Hwaet!” and turns it into “Bro!”