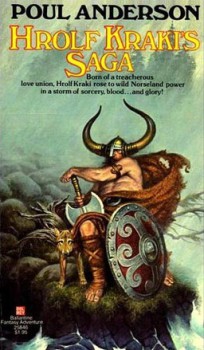

The Whole Northern Thing: Hrolf Kraki’s Saga by Poul Anderson

Doom: Old English dom “law, judgment, condemnation,” from Proto-Germanic *domaz (cf. Old Saxon and Old Frisian dom, Old Norse domr

For a crime committed by King Frodhi the Peace-Good against the giantesses Fenja and Menja, a great doom is laid on the royal family of Denmark, the Skjöldungs.

How that doom works its murderous effects on the Skjöldungs is the core of Hrolf Kraki’s Saga (1973), Poul Anderson’s gripping retelling of the sagas (read the original here) of the ancient Danish king, Hrolf. The book brings together the extant stories of the Skjöldungs (which, almost as an aside, include the tale of Beowulf) and welds them into a coherent novel of great potency.

According to legend, Hrolf was the greatest king of Denmark and the most outstanding member of the semi-divine Skjöldung family. With his canny intelligence, he thwarted most of his kingdom’s enemies and built up its wealth. His great nobility drew the North’s mightiest warriors to his court.

Whether real or mythical, Hrolf and his reign are remembered in Denmark as fondly as Arthur’s in Britain. And like Arthur, all Hrolf’s great works were destroyed and chaos ruled in his wake.

From a people whose myths foretold the annihilation of the gods themselves in the end times of Ragnarok, the bleakness that runs through so many of their stories isn’t surprising. Perhaps it’s traceable to the violence of the Great Migratory period when the Germanic people spread out from their ancient homelands in Scandinavia and northern Germany and came into conflict with the Roman Empire and Celtic tribes in Gaul and Britain. Maybe it was just the cold and diminished winter sunlight in Norway and Sweden that bred their melancholy. Whatever the causes, doom in its modern sense runs through almost every chapter of Hrolf Kraki’s Saga.

Anderson’s novel is divided into several separate sagas which build toward the telling of the great reign of Hrolf Kraki and his kingdom’s subsequent destruction. The first,”The Tale of Frodhi,” is about the aftermath of King Frodhi Peace-Good’s death and the joint rule of his sons Halfdan and Frodhi. The former is wise and peaceful, the latter greedy and warlike. In a prefiguring of a later Danish king, Frodhi kills his brother and marries his sister-in-law. The rest of the tale tells of Hroar’s and Helgi’s quest to avenge their father, Halfdan.

“The Tale of the Brothers” recounts Halfdan’s sons’ co-reign over Denmark and the dooms Helgi brings on himself and his son. In his  foreword, Anderson makes clear he had no intention of softening the almost casual brutality and callous violence common to the period and the original legends. The central event of this story is the kidnapping and rape of a Saxon queen, Olof, by Helgi after she rejects his marriage proposal and humiliates him. That horrible event leads directly to the birth of Helgi’s son Hrolf and Helgi’s own death at the hands of his son-in-law.

foreword, Anderson makes clear he had no intention of softening the almost casual brutality and callous violence common to the period and the original legends. The central event of this story is the kidnapping and rape of a Saxon queen, Olof, by Helgi after she rejects his marriage proposal and humiliates him. That horrible event leads directly to the birth of Helgi’s son Hrolf and Helgi’s own death at the hands of his son-in-law.

With Hroar’s death, Hrolf becomes the sole king of Denmark. Like his Uncle Hroar, he is smart and just and he builds up his kingdom. Like his father Helgi, he is a brave warrior and he leads his men into battle against both viking raiders from the North and Saxon ones from the South. Under his rule, Denmark becomes rich and a beacon of peace and justice.

Turning aside from the rule of the Skjöldung king, “The Tale of Svipdag” and “The Tale of Bjarki” introduce the two greatest warriors of the North who will serve King Hrolf in peace as well as in war. Svipdag is a Swedish farmer’s son who seeks his fortune in the service of the sorcerer-king of Sweden. Bjarki is the third son of a Norwegian prince, cursed by his evil Finnish stepmother to change into a bear every morning. His oldest brother has the legs of an elk and his second the feet of a hound.

There are fantastic elements throughout Hrolf Kraki’s Saga, but it’s in “The Tale of Bjarki” that they become dominant. Previously, the book has some strange births and mysterious goings-on, but from this tale on there are rampant magic weapons, monsters, and evil sorcerers.

Early in his service to Hrolf, Bjarki fights a fiend no other warrior has been able to defeat:

The Norseman unslung his shield and went to meet the monster.

It saw him, swung on high and readied itself to stoop: a featherless thing of huge sickling wings, cruel claws and beak, tail like a lashing rudder, scaly crest above snaky eyes. Bjarki planted his feet and laid a hand on sword hilt.

As the story of Hrolf and the Skjöldungs builds to its climax, it’s as if all the powers of evil are unleashed in order to ensure their doom.

The final chapters of the book, “The Tale of Yrsa,” “The Tale of Skuld,” and “The Tale of Vögg,” recount the last great battles of Hrolf and his retainers. The first story tells of Hrolf’s raid on Sweden to avenge his father and mother. The second is about the great war between Hrolf and his half-sister, Skuld. She was born of their father’s tryst with an elf and as she grew up, she committed herself to the darkest of magics. Driven by tremendous greed and jealousy, Skuld seeks to overthrow her brother. The final story is the shortest of the book and reports the final action in Hrolf and Skuld’s war and its terrible aftermath.

Like many others, I am in thrall to “the Northern thing.” Some of the earliest fantasy authors such as William Morris and E. R. Eddison were equally captivated and started by translating Norse sagas. That’s a phrase first used by the poet W. H. Auden in speaking about J.R.R. Tolkien. It refers to the great body of Norse and German mythology and legends. Some, like many of the Sagas of Iceland, are about normal men and their lives (although a disproportionate number of those seem to have been outlaws). Others, like the Nibelungenlied, tell the exploits of heroes. Others yet, like the Prose Edda, are about the creation of the cosmos and the adventures of Odin, Thor, and the rest of the gods.

There’s a fierceness in these stories I find exhilarating. The world of my Norse forebears (my grandfather was Norwegian and Danish and raised in Sweden; my grandmother was a Swede Finn who spent several years in Finland and told me stories of tomtegubbes sneaking around the farm) was an often savage place. To survive, let alone achieve greatness, the heroes, and even gods, needed great courage and strength. Even in the face of certain doom, the Norse heroes stand fast and never retreat, and I find that deeply appealing.

During the battle against Skuld, one of Hrolf’s retinue shouts out:

Hjalti the High-Minded chanted in glee:

“Many a byrnie is now in tatters, many a helmet clove and many a bold rider stabbed down from the saddle. Still our king is of good heart, as glad as when he cheerily drank ale, and mighty are the blows of his hands.

The heroes in Hrolf Kraki’s Saga are bold and alive. There’s a vibrancy to them that nearly shouts from the page. They’re human enough that they’re not distanced from the reader by divinity and perfection. Despite the magic around them, they are demonstrably, at times despairingly, human. Hrolf and Bjarki are as heroic as Arthur and Lancelot. Helgi is broken and causes great damage, but still aspires to a kind of nobility and inspires deep sympathy. Anderson’s prose helps expose the tragic nobility that courses through this collection of fifteen-hundred-year-old legends.

Poul Anderson, born of Danish parents, was mostly a writer of good, solid science fiction. What too few people know is that he was also a writer of some excellent swords & sorcery, most notably The Broken Sword (reviewed in Black Gate by Ryan Harvey). While that novel is a wholly original story crafted of Norse elements, Anderson worked from the original sources for Hrolf Kraki’s Saga. Prompted by Lin Carter, Anderson set out to translate poetic verses from the original saga for the pages of Amra.

The actual saga proved more fragmentary and disjointed than Anderson had remembered. He decided to follow his own best writerly instincts and fill in the gaps himself. To provide a rationale for telling the story in prose, he presents it as a series of nightly tales told to King Aethelstan by the wife of a Danish soldier in service to the English king.

I’m no scholar of Norse myths and legends, and I can’t attest to the accuracy of the choices Anderson made in repairing the holes in Hrolf Kraki’s Saga, but what I can attest to is the greatness of this fantastic collection of brooding, Northern tragedies.

I’m not familiar with these tales in particular or the book that Poul Anderson based on them, but I would hazard to guess that he was correct to “fill in the gaps” so to speak. I base this on two things.

The first is that Mr. Anderson was a great writer with excellent instincts that I’ve seen proven time and again with the many works of his I’ve read. The second is the difference between the mind of primitive man and modern man.

Primitive man had a more (for lack of a better term) magical way of thinking. Logic and internal consistency were not very important to our ancestors. For modern man it’s important that things make sense in some fashion. If it doesn’t we’re likely to reject the whole thing.

Sounds like a good book, I’ll have to check it out.

As a guy who has been in thrall to the “Northern Thing” for much of my life, I’ve found one of the most memorable things about the sagas is their darkly amusing, almost perversely stoic, wit.

No matter how ghastly circumstances get these Nordic fellows have a dry understatement to make about it.

Two foes clash and when they draw apart one finds that his upper lip has been cut away.

To his foe he says, “”I was never beautiful, but you have made no improvement.”

How can you not admire an attitude like that?

@ Rigel-K – I understand and agree with what you’re saying and am in total agreement with your opinion of the later Poul Anderson’s talents.

What I meant, though, was the interpretations he made of various fragments of the saga and how pieces from different sources best fit together.

@J Hocking – Absolutely! Where’s the line you quote from? That’s perfect.

I’m captivated by the grim determination to carry on in the face of certain annihilation. The image from the D’Aulaires’ Book of Norse Myths (which I’m going to write about on my own blog a little) of Odin riding into the maw of the Fenris Wolf and certain doom is etched into my brain.

> “”I was never beautiful, but you have made no improvement.”

I’ve tried to say that line out loud without using my upper lip… and it’s hard!

These Nordic fellows. Always showing off.

“These Nordic fellows. Always showing off.”

Yeah, but they have so much to show off about.

Damn, how could I have missed this? There is a gap in my knowledge of the genre, as bare as a snail out of its shell!

Hello, Amazon.

John Hocking rightly notes the grim humor that (rarely) appears in the sagas. I seem to remember that there’s one in which a warrior is speared and someone (probably himself) examines his wound. Noting the layer of fate, he praises the warrior’s lord for feeding his men well — something like that.

There’s one in which some warriors are playing a game, perhaps with dice, and someone swipes off a man’s head. The decapitated head speaks the number he rolled. (Again, I’m not sure of the details — don’t have the books at hand.) If you watch Werner Herzog’s movie Aguirre, you’ll see something like this, also a scene in which a conquistador is shot with an arrow or spear and says short arrows/spears are becoming fashionable — or something like that! — before tumbling over dead.