Goth Chick News: Death Always Comes at the End

Okay, not a cheery thought, but you aren’t reading Martha Stewart’s Living as you well know.

Okay, not a cheery thought, but you aren’t reading Martha Stewart’s Living as you well know.

Back when I was a fledgling Goth Chick, learning the joys of sitting cross-legged for hours on end in the aisle of my local bookstore, but not yet in love with a particular genre (just no romance novels, ever), a somewhat twisted piano teach handed me an Agatha Christie novel.

I say “twisted” because one could argue that such tales were in no way appropriate fare for a nine-year-old. Then again, when taken in the context of the other media available to this age group today, Agatha’s plot lines are probably fit for the Disney channel.

But I digress.

My piano teacher looked like she was fresh from an audition for the part of a matronly, widow piano teacher. She even had her lines memorized, scolding me exactly the same way every week while I banged on the keys through purgatorial scales and off-kilter renditions of Ode to Joy. But in keeping with my life-long theme which at that point was only a mere pattern, she was a bit left of center.

Only a few months ago, I would never have believed that I would end up writing two convention reports within the space of a month. Yet here I am bringing you news of

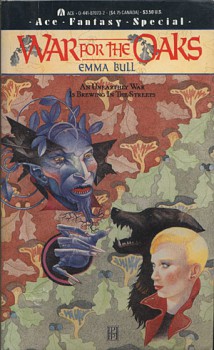

Only a few months ago, I would never have believed that I would end up writing two convention reports within the space of a month. Yet here I am bringing you news of  War for the Oaks, by Emma Bull

War for the Oaks, by Emma Bull

Hampered this past week by a bad cold, I’ve made only minimal progress in

Hampered this past week by a bad cold, I’ve made only minimal progress in