Solitaire Gaming

I blame the whole thing on John O’Neill.

A few years back I asked him about the solo Dark City Games adventures that Andrew Zimmerman Jones and Todd McCaulty had reviewed so favorably for Black Gate. John happens to have a larger game collection than most game stores, so I’d come to the right person.

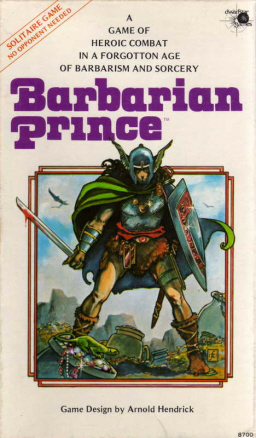

Solo games were great fun, John told me. “Here’s an extra copy of an old game you’ve never heard of that’s really cool. Go play it.”

That was Barbarian Prince. And yeah, it was pretty nifty (you can try it out yourself with a free download here, along with its sister solitaire product, Star Smuggler).

I started playing and enjoying the products created by Dark City Games, which the rest of the staff and I have continued to review for the magazine.

But what are these solitaire games like?

But what are these solitaire games like?

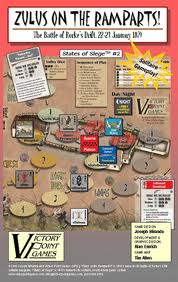

The most obvious analogy is to say that solitaire games are a little like computer adventure games played with paper, with dice and cards taking the place of a computer game’s invisible randomization of results.

My first thought was something along the lines of “how quaint,” but it turns out that while the play experiences are similar, the flavors are slightly different, even if playing them stimulates similar centers of the brain.

It’s like switching off orange pop to try some root beer, or vice versa. You may not drink one or the other exclusively, but they both sure are sweet on a hot day.

While playing a solitaire game you may not see any computer graphics, but your imagination will paint some images for you.

And there’s the tactile pleasure of manipulating the counters and looking over the game board and flipping through the booklet and rolling the dice.

Solitaire in no way means that you will get the same game play each time, and to my surprise I’ve discovered that a well designed solo board game has better replay value than many computer games.

Last week, I discussed my

Last week, I discussed my  I’ve been thinking lately about fantasy in the 1980s. More specifically, about the wave of fantasy fiction that began to be published in the late 70s, in the wake of The Sword of Shannara and the first Thomas Covenant books, and which over the following years developed into fantasy as we know it now. So far as I can learn, it seems that this was when fantasy really took root as a novel category — that is, when fantasy novels stopped being relatively rare events and began to flourish as a genre. As a result, I think, it was a time when the idea of fantasy broadened; new ideas and forms and voices were tried, even if certain assumptions (like a quasi-medieval-European setting) were often unquestioned. What I wonder is whether certain things tried then and since almost forgotten are in fact worth revisiting.

I’ve been thinking lately about fantasy in the 1980s. More specifically, about the wave of fantasy fiction that began to be published in the late 70s, in the wake of The Sword of Shannara and the first Thomas Covenant books, and which over the following years developed into fantasy as we know it now. So far as I can learn, it seems that this was when fantasy really took root as a novel category — that is, when fantasy novels stopped being relatively rare events and began to flourish as a genre. As a result, I think, it was a time when the idea of fantasy broadened; new ideas and forms and voices were tried, even if certain assumptions (like a quasi-medieval-European setting) were often unquestioned. What I wonder is whether certain things tried then and since almost forgotten are in fact worth revisiting. The Birthing House

The Birthing House Due to an unfortunate (or perhaps I should say, “fortuitous”) comment I let slip in an email, Howard Andrew Jones discovered I had no idea who C.L. Moore was.

Due to an unfortunate (or perhaps I should say, “fortuitous”) comment I let slip in an email, Howard Andrew Jones discovered I had no idea who C.L. Moore was.

I’ve contributed book reviews to the

I’ve contributed book reviews to the

Not to beat the subject, like Fingon, to death, but neither writer is trod into the mire by a comparison to the other. The shortest distance between these two towers is the straight line they draw and defend against the dulling of our sense of wonder, the deadening of our sense of loss, and the slow death of imagination denied.

Not to beat the subject, like Fingon, to death, but neither writer is trod into the mire by a comparison to the other. The shortest distance between these two towers is the straight line they draw and defend against the dulling of our sense of wonder, the deadening of our sense of loss, and the slow death of imagination denied. “The 25th anniversary edition of The Last Starfighter.”

“The 25th anniversary edition of The Last Starfighter.”