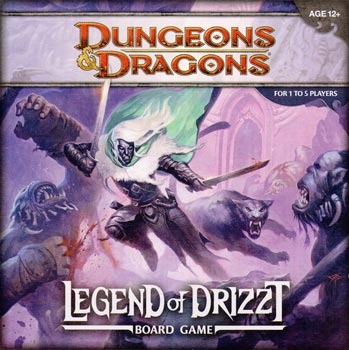

New Treasures: The Legend of Drizzt

I love board games. But after collectible card games and computer games pretty much swept the market clean of them in the mid-90s, it seemed the era of the board game was over. I put away my copies of Dragon Pass and Divine Right, and pretty much accepted the fact that I’d be explaining the quaint concept of “board games” to my grandkids. Assuming I could get them to put down their Xbox controllers long enough.

I love board games. But after collectible card games and computer games pretty much swept the market clean of them in the mid-90s, it seemed the era of the board game was over. I put away my copies of Dragon Pass and Divine Right, and pretty much accepted the fact that I’d be explaining the quaint concept of “board games” to my grandkids. Assuming I could get them to put down their Xbox controllers long enough.

Then an interesting thing happened in the middle of the last decade: The board game experienced something that almost looked like a resurgence. Enticed by Settlers of Catan and a series of popular titles from Fantasy Flight, gamers began to cautiously put down their controllers and cluster curiously around kitchen tables again.

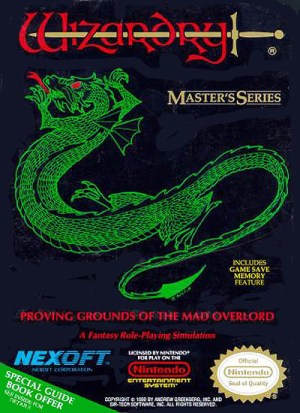

Wizards of the Coast took notice and tossed their hat in the arena with several very well received games, including Ikusa and the epic Conquest of Nerath, both of which Scott Taylor reviewed for us here.

With just a few titles, WotC has become a heavyweight in fantasy board games — and they show no signs of slowing down.

Earlier this month a box landed on my doorstep (with a resounding thud) containing a review copy of their latest entry: The Legend of Drizzt, a massive 7-pound contender that has every appearance of being another winner.

I recently caught up with Paizo’s James Sutter for a conversation about his work heading up Pathfinder’s new fiction line, as well as his own writing and influences. In part one of our conversation James tells us about his new novel for Pathfinder,

I recently caught up with Paizo’s James Sutter for a conversation about his work heading up Pathfinder’s new fiction line, as well as his own writing and influences. In part one of our conversation James tells us about his new novel for Pathfinder,

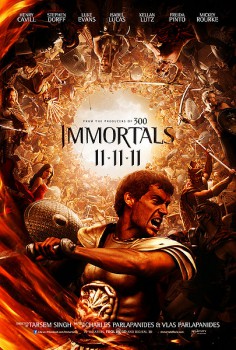

Immortals (2011)

Immortals (2011) Young adult fiction has a lot going for it in recent years. In the wake of the Harry Potter craze, there’s an entire generation of young people who have grown up with the understanding that reading is a cool way to spend your time and entertain yourself.

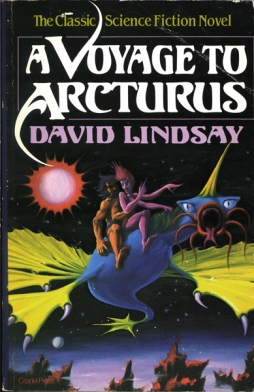

Young adult fiction has a lot going for it in recent years. In the wake of the Harry Potter craze, there’s an entire generation of young people who have grown up with the understanding that reading is a cool way to spend your time and entertain yourself. Writing about Romanticism has gotten me started thinking about forms, and conventions, and how we read a story. To some extent I’ve come to feel that contemporary ways of reacting to narrative are more classical than romantic; they’re more to do with structure and form than with trusting the individual genius. It seems to me that many readers, and critics, have become used to looking for certain things in a story, and have come to think of stories that function in a different manner as necessarily defective rather than distinct. And I feel this is a pity, since if we can’t accept the strange works of genius that succeed in defiance of everything we think we know about storytelling, then our experience of story becomes diminished.

Writing about Romanticism has gotten me started thinking about forms, and conventions, and how we read a story. To some extent I’ve come to feel that contemporary ways of reacting to narrative are more classical than romantic; they’re more to do with structure and form than with trusting the individual genius. It seems to me that many readers, and critics, have become used to looking for certain things in a story, and have come to think of stories that function in a different manner as necessarily defective rather than distinct. And I feel this is a pity, since if we can’t accept the strange works of genius that succeed in defiance of everything we think we know about storytelling, then our experience of story becomes diminished.