Fantasy Out Loud

Nearly every night, I read aloud to my boys. For Evan, my seven-year-old, I have lately been reading The Hobbit. Two nights ago, no sooner had I begun than Evan interrupted, saying, “It’s funny how they spell ‘Smaug.’”

Nearly every night, I read aloud to my boys. For Evan, my seven-year-old, I have lately been reading The Hobbit. Two nights ago, no sooner had I begun than Evan interrupted, saying, “It’s funny how they spell ‘Smaug.’”

“Oh?” I asked. “How would you spell it?”

“S-M-O-G.”

“Good,” I said. “That is how you would normally spell it.” But privately, I thought how wonderful it was that Tolkien chose this other, more evocative spelling. It also occurred to me that without Evan’s commentary, I might not have even noticed.

What we choose to read to our children has ramifications almost beyond counting. Certainly, a shared reading experience is pivotal to the in-home dynamics and shared knowledge of any family, but insofar as one tackles a diet of writing that qualifies as “fantastic,” reading aloud is also crucial to the development and enculturation of an entire new generation of fantasy readers. Given a world that grows ever more hectic, and therefore has less and less time for “pleasure” reading, this is no small thing.

I am fortunate to have two children, both boys, and I can see the results of my reading choices –– the goblin fruit, as it were, of my labor –– as if I had scrawled on their souls with indelible ink. Corey, my older boy, now reads nothing but fantasy fiction, at least not by choice. (He has also, to my dismay, discovered comics, and for this, too, I blame myself.)

This week concludes Black Gate‘s interview with author and editor James L. Sutter with a discussion of the pros and cons of media-tie in fiction, the Before They Were Giants anthology which collects the first sale short fiction of many big name writers, and a look at what James is working on now. Be sure to check out parts

This week concludes Black Gate‘s interview with author and editor James L. Sutter with a discussion of the pros and cons of media-tie in fiction, the Before They Were Giants anthology which collects the first sale short fiction of many big name writers, and a look at what James is working on now. Be sure to check out parts

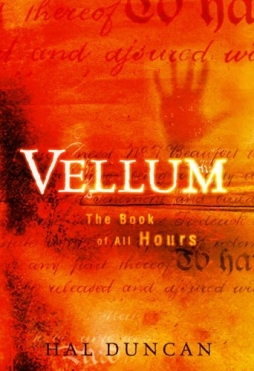

Hal Duncan’s The Book of All Hours is a dazzling, fascinating, frustrating work. A duology consisting of 2005’s Vellum and 2007’s Ink, it plays with structure and story in powerful ways, while also seeming to fall back too easily into black-and-white absolutes and traditional forms. The oddity of the book is that although in some ways it appears radically new, in other ways, as one reads further into it, it comes to feel more and more familiar.

Hal Duncan’s The Book of All Hours is a dazzling, fascinating, frustrating work. A duology consisting of 2005’s Vellum and 2007’s Ink, it plays with structure and story in powerful ways, while also seeming to fall back too easily into black-and-white absolutes and traditional forms. The oddity of the book is that although in some ways it appears radically new, in other ways, as one reads further into it, it comes to feel more and more familiar.