Romanticism and Fantasy: The French Experience

In my previous posts about Romanticism and fantasy, I looked at British literature in the 18th century through to 1789, and tried to track the emergence of a certain kind of fantastic fiction. In order to understand what happens in British writing (and politics) after 1789, though, we have to look at what happens in France.

In my previous posts about Romanticism and fantasy, I looked at British literature in the 18th century through to 1789, and tried to track the emergence of a certain kind of fantastic fiction. In order to understand what happens in British writing (and politics) after 1789, though, we have to look at what happens in France.

Before continuing, I need to emphasise: I am not an academic, or a professional historian. I’ve read a fair amount about the period, and I have an intense fascination with Romantic literature in English. These posts come out of that fascination, and are an attempt to relate what I see in that literature with the contemporary fantasy fiction that seems to me to be its direct descendant. All of which is to say that in writing about French literature and history, I am even more of a dilettante than in discussing British writing. There are people who dedicate their lives and careers to making sense of these subjects, and dissecting their various meanings; I am not one of them.

Having said that, it seems to me that the element of fantasy I found in English literature in the late eighteenth century was not present in contemporary French writing in the same way, or to the same degree. In Britain, it seems almost as though the suppression of the fantastic by neo-classical norms led to its eruption later in the century, at first under cover of antiquarianism, then more and more openly. In France, even more classical in its orientation than Britain, that process didn’t happen; instead it seems another type of fantastic fiction came to prominence.

Spiral Hunt

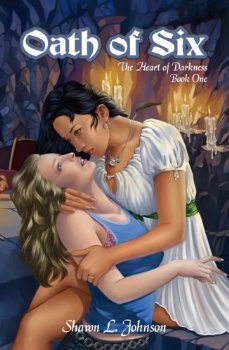

Spiral Hunt It took me years to complete the first draft of Oath of Six, the first volume in my fantasy series The Heart of Darkness.

It took me years to complete the first draft of Oath of Six, the first volume in my fantasy series The Heart of Darkness.