Behind the Mask: The Abominable Dr. Phibes from Script to Screen

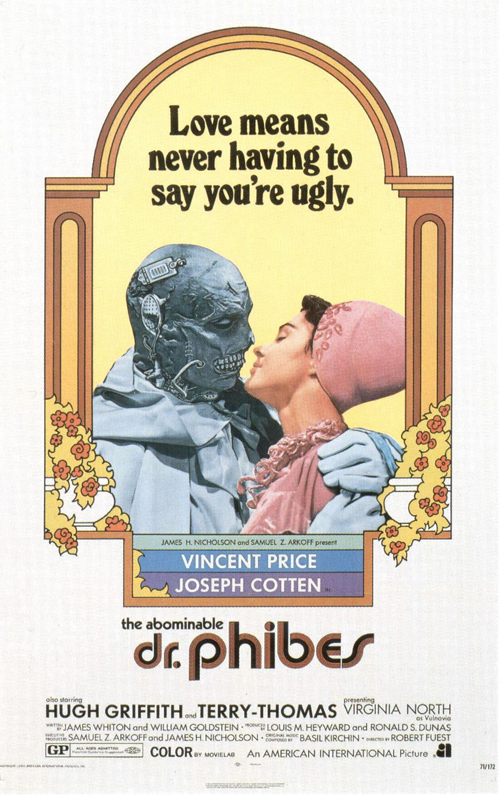

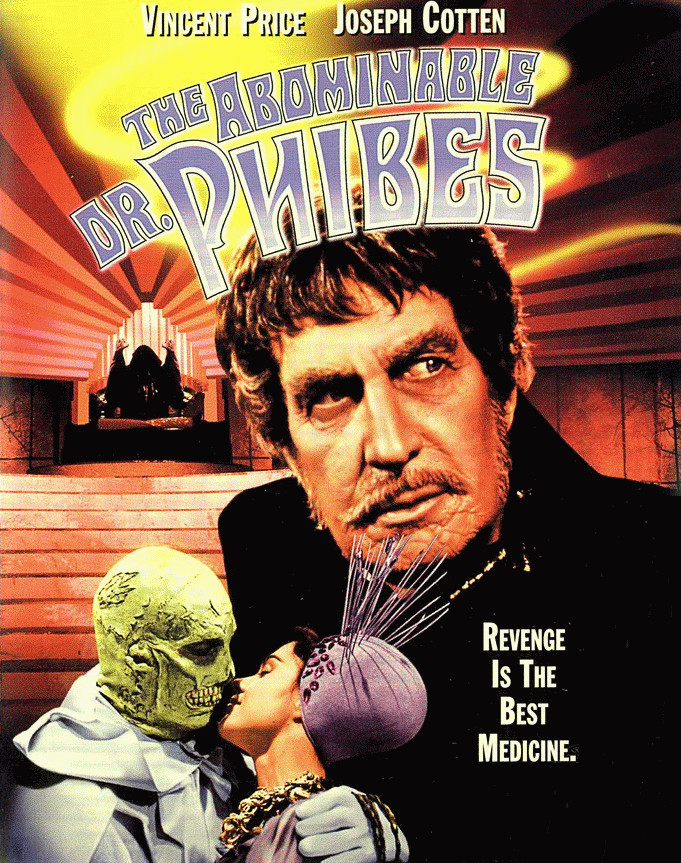

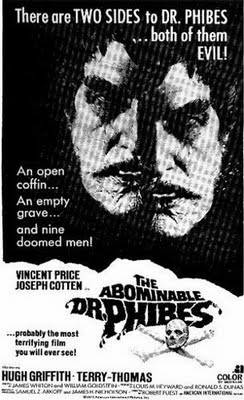

The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971) starring Vincent Price has long been one of my favorite films. I re-visit it once or twice each year and it always retains a freshness and vitality that separates it from other movies that I love. When asked to explain why it resonates with me to such a degree, I would invariably state that it is the perfect mix of horror and comedy. It never descends into the level of a spoof, but it has a delightfully anachronistic and intentionally offbeat bent with its art deco sets, lurid murders, campy score, and over-the-top performances. The film is a valentine to the mystery fiction of Edwardian England that saw the transition from Sherlock Holmes to Dr. Fu Manchu, but filtered through modern sensibilities that delight in the sensationalistic villainy and the preposterousness of detectives matching wits with murderers as if they were schoolboys playing a game.

The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971) starring Vincent Price has long been one of my favorite films. I re-visit it once or twice each year and it always retains a freshness and vitality that separates it from other movies that I love. When asked to explain why it resonates with me to such a degree, I would invariably state that it is the perfect mix of horror and comedy. It never descends into the level of a spoof, but it has a delightfully anachronistic and intentionally offbeat bent with its art deco sets, lurid murders, campy score, and over-the-top performances. The film is a valentine to the mystery fiction of Edwardian England that saw the transition from Sherlock Holmes to Dr. Fu Manchu, but filtered through modern sensibilities that delight in the sensationalistic villainy and the preposterousness of detectives matching wits with murderers as if they were schoolboys playing a game.

While all of the above is certainly true, my attraction to the material runs deeper. Viewing the film as a valentine to Edwardian thrillers sparked a thought about Halloween. For most, it is a time for children to play dress-up and collect candy from their neighbors, but there is another side to the holiday that is decidedly grim. Halloween also evokes sadness and tragedy, lost love, memories of happiness never to be reclaimed, it is fitting it is an Autumnal holiday for it is a celebration of the bittersweet and the tragic. I suspect that is the root of what leads some adults to still cling to the Classic Horror films of the last century before horror became synonymous with splatter films and torture porn. Horror used to be reflective of unfortunate lives, lamentations of those cursed or forsaken. That association is still strong for those who are out of step with the world around them and feel separated from the rest of the world by the weight of their pain. Halloween and Classic Horror are a remembrance of our painful pasts that we transfer to entertainments depicting others’ pain and torment.

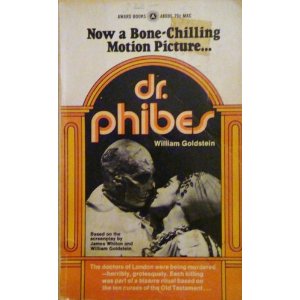

Unsurprisingly since The Abominable Dr. Phibes marked the transition from Classic to Modern Horror, the character of Dr. Phibes is a tragic one despite his madness and the atrocities he commits. William Goldstein created the character in an unpublished story he called “The Finger of Dr. Pibe” (as the character’s name was originally rendered). Along with James Whiton, Goldstein adapted the story as a screenplay entitled The Curses of Dr. Pibe. The script was optioned and found its way to AIP, a regular distributor of drive-in exploitation fare then in its waning days. Along with the novel, Dr. Phibes that Goldstein would author as a movie tie-in for Award Books in the US and Tandem Books in the UK, there is a consistency in these seminal works that laid the foundation for the film and that is the fact that the material is completely lacking in the camp humor that director Robert Fuest and star Vincent Price would delight in bringing to the screen.

For those familiar only with the film, this may sound disappointing for it would seem to rob the property of all its color and joy. An initial reading of the script for one who reveres the film would likely elicit such a response, but the truth is Goldstein’s vision in his original story, the script and his novel are the heart that beats beneath the film. Truth be told, The Abominable Dr. Phibes is a tragic love story. Phibes is portrayed as a true Renaissance man – a physicist, a world class organist, and a scholar, but his greatest passion is for his wife Victoria who died of uterine cancer several years before the story begins. Phibes suffers a near-fatal car accident while rushing to his wife’s side during her emergency hysterectomy. The world believes him dead, but he survives to construct his own separate reality within the confines of his home in Belgravia. Phibes’ world is a shrine to his late wife. He retreats in his passion for music and invention by building a world of lifelike automatons to serve as his mute companions. Phibes doesn’t hide from his pain so much as he retreats within it and in that, he shares much in common with the other characters Goldstein shapes.

For those familiar only with the film, this may sound disappointing for it would seem to rob the property of all its color and joy. An initial reading of the script for one who reveres the film would likely elicit such a response, but the truth is Goldstein’s vision in his original story, the script and his novel are the heart that beats beneath the film. Truth be told, The Abominable Dr. Phibes is a tragic love story. Phibes is portrayed as a true Renaissance man – a physicist, a world class organist, and a scholar, but his greatest passion is for his wife Victoria who died of uterine cancer several years before the story begins. Phibes suffers a near-fatal car accident while rushing to his wife’s side during her emergency hysterectomy. The world believes him dead, but he survives to construct his own separate reality within the confines of his home in Belgravia. Phibes’ world is a shrine to his late wife. He retreats in his passion for music and invention by building a world of lifelike automatons to serve as his mute companions. Phibes doesn’t hide from his pain so much as he retreats within it and in that, he shares much in common with the other characters Goldstein shapes.

The novel, Dr. Phibes fleshes out the colorful backgrounds of each member of the medical team that Phibes has marked for death. The story is rich in Goldstein’s Jewish heritage from a character’s cynical assessment of the Eternal City that he visited expecting to be enraptured by its beauty to Phibes’ association of his own tragic pain with that of the unjust suffering of the Jewish people under Egypt three thousand years earlier. God visited the ten curses of the G’tach upon Egypt for their cruelty and so Phibes, creator of his own self-contained world, visits the same curses upon those he holds responsible for his wife’s death – the surgical team entrusted with saving her life. Phibes’ Passover can only come once the plagues have brought just retribution to those who destroyed his ability to function in the world.

While the film is content to show each death solely from the perspective of the escalating outrageousness of each grisly murder, in his novel Goldstein shows us how each of the team (like Phibes) has retreated in a world of their own making. While Phibes’ love for his wife is pure, only Dr. Vesalius (who has retired into a reclusive life in his townhouse with its model trains, works of art, chess games with his beloved son, and the promise of a book yet to be completed) is portrayed as a similar man of integrity. The rest of the surgical team is marked by their vices. Their appetites for food and sex preclude their ability to relate to others or to find love and lasting happiness. These talented doctors are lust-filled men whose proximity to death has seemingly robbed them of the ability to be human, to be a mensch. They are marred by their lechery, their contempt for women, their disregard for the general public, their addiction to pornography, their obesity, and their self-aggrandizement. This lack of humanity, retreating to a world comprised solely of one’s own passions in an attempt to manage the pain of love lost forever (as in Phibes’ wife and Vesalius’ son) or of peace never known are the themes that drive the story.

While the film is content to show each death solely from the perspective of the escalating outrageousness of each grisly murder, in his novel Goldstein shows us how each of the team (like Phibes) has retreated in a world of their own making. While Phibes’ love for his wife is pure, only Dr. Vesalius (who has retired into a reclusive life in his townhouse with its model trains, works of art, chess games with his beloved son, and the promise of a book yet to be completed) is portrayed as a similar man of integrity. The rest of the surgical team is marked by their vices. Their appetites for food and sex preclude their ability to relate to others or to find love and lasting happiness. These talented doctors are lust-filled men whose proximity to death has seemingly robbed them of the ability to be human, to be a mensch. They are marred by their lechery, their contempt for women, their disregard for the general public, their addiction to pornography, their obesity, and their self-aggrandizement. This lack of humanity, retreating to a world comprised solely of one’s own passions in an attempt to manage the pain of love lost forever (as in Phibes’ wife and Vesalius’ son) or of peace never known are the themes that drive the story.

The film portrays Trout and Schenley, the Scotland Yard men investigating the murders as a barely competent Holmes and Watson double act. They are the viewer’s touchstone to the normal world as their lives are not artsy, fantastic, or colored with the intensity of their passions. In the film, Phibes and his victims live in an art deco world gone mad while Trout and Schenley are drearily normal characters with familiar personalities in this world of the outré. This differs from Goldstein’s original conception of Trout as an investigative reporter while in the novel, both men are Scotland Yard detectives, but they are far from genre stereotypes. Schenley is much more than a Watson, he is the character Phibes and Vesalius would be without the tragedy of their respective marriages. Schenley is the humble hero of the First World War who prefers the anonymity of a quiet life of a detective sergeant with the Yard who can retreat to his home with his loving wife and family without any pomp and fanfare over his wartime accomplishments. Trout is the stellar younger man, still in his early twenties, already risen to the rank of detective inspector but whose brash recklessness leaves him always one step away from career disaster.

Surprisingly, Phibes is the character whose role in the novel is marginalized yet he seems all the more effective for its climatic revelation of how he completes the puzzle not only of the mystery, but of the greater theme of shattered lives coping with a harsh reality by retreating into their own id. Goldstein dedicates the novel to Dr. Phibes. Initially it seems an odd conceit, treating a fictional villain as a living, breathing person and yet, in retrospect, it is oddly appropriate for it is only in the pages of the script and his novel that Phibes is treated with the seriousness that his pain demands. Fuest’s camp classic film turns the tragedy into comedy and one is always aware they are watching a theater of the absurd. The novel gives us real people in the form of doctors, inventors, musicians, rabbis, aerialists, art collectors, chess players, craftsmen, and artisans whose lives are marked with passion and pain to the degree that they have fallen irretrievably out of step with the world around them. From that perspective, Goldstein’s dedication seems entirely appropriate for who other than the creator of his own world could better understand the pain from which he is escaping.

William Patrick Maynard was authorized to continue Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu thrillers beginning with The Terror of Fu Manchu (2009; Black Coat Press). A sequel, The Destiny of Fu Manchu is coming in early 2012 from Black Coat Press. Also forthcoming is a collection of short stories featuring an original Edwardian detective, The Occult Case Book of Shankar Hardwicke and an original hardboiled detective novel, Lawhead. To see additional articles by William, visit his blog at SetiSays.blogspot.com

Oddly enough, this has always been one of my favorite films, along with its sequel.

Having been very nearly raised at the drive-in, feeding on a steady diet of Hammer films and similar horror fare, my poor little twisted mind found pleasure in both the comparative colofulness of the films and their hugely inventive ways of killing folks off.

With my ghoulish atraction to pretty much any film starring Vincent Price, along with my fondness for the “artfully themed murders” found in such films as Theater of Blood, etc., Phibes, et al really scratched my itch.

And their campiness offered just enough of a reprieve to allow me to forego my usual antidote of reading several “funny” comic books once I’d returned home, to help keep the nightmares away. (I was eight years old in 1971 😉 )

Alas, I’ve found very few folks over the years to share my fondness for Phibes, despite several tries.

Gruud, if you’re not a member of Yahoo’s Phibes group, you should take a look at it. There are wondeful resources available in the files and the conversations can be quite informative.