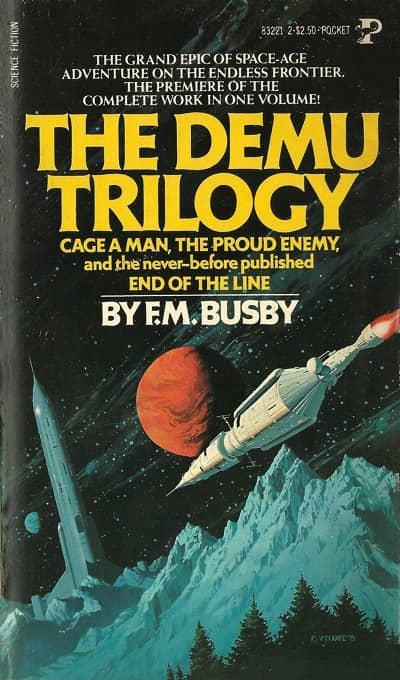

Vintage Treasures: The Demu Trilogy Omnibus by F.M. Busby

|

|

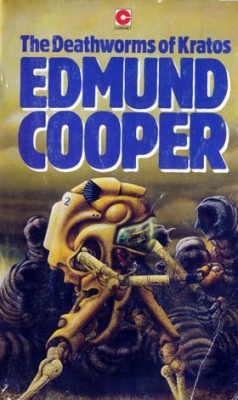

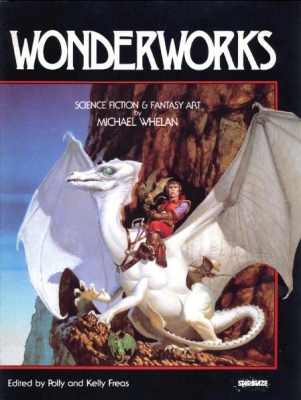

Cover by Vincent di Fate

F.M. Busby was a well known science fiction fan who graduated to professional writer in the early 70s. He won a Hugo in 1960 for his fanzine Cry of the Nameless, and when he took early retirement in 1971 he became a full time science fiction writer at the age of 50. He was enormously productive for the next quarter century, publishing 19 novels and numerous short stories between 1973 and 1996.

He never broke out of midlist, and gave up writing after that, blaming the infamous Thor Power Tools ruling in an email to fan George Willick.

No, I haven’t been writing fiction for some time. Many if not most of us “midlist” writers have been frozen out like a third party on an Eskimo honeymoon. The IRS started it by getting the Thor Power Tools decision stretched to cover an inventory tax on books in publishers’ warehouses (so they don’t keep ’em in print no more), and the bookchains wrapped it up by setting one book’s GROSS order on that writer’s previous book’s NET sales. 4-5 books under those rules, and you’re road kill; a publisher can’t be expected to buy a book the chains won’t pay out on.

Busby (“Buz”) produced four novels in The Rebel Dynasty (Star Rebel, Rebel’s Quest, The Alien Debt, and Rebels’ Seed), three Rissa Kerguelen novels, and the Slow Freight trilogy. But his most popular series was probably The Demu Trilogy, which Pocket Books kept in print for nearly seven years in an omnibus collection.