When you have kids, I think it’s inevitable that you want them to read the books you loved most as a child. You parents out there know what I’m talking about. And be honest. It’s not enough for them to just read ’em, is it? No. You want your kids to love those books, the same way you did.

When you have kids, I think it’s inevitable that you want them to read the books you loved most as a child. You parents out there know what I’m talking about. And be honest. It’s not enough for them to just read ’em, is it? No. You want your kids to love those books, the same way you did.

I’ve had pretty spotty luck, frankly. Couldn’t get any of my children interested in Alfred Hitchcock and the Three Investigators, for example. Sometimes I despair for future generations. I had a bit more luck with my teenage boys and the classic SF and fantasy of my own early teens, such as Dune and Lord of Light. (Asimov’s Foundation Trilogy was a complete bust, however).

But in terms of reaching all three of my kids, both boys and my 13-year old daughter? Almost impossible.

Except for a few slender volumes from Scholastic Books, that is. Scholastic Books were some of the great treasures of my childhood, and I loved them with a fierce passion. Norman Bridwell’s How To Care For Your Monster, John Peterson’s The Secret Hide-Out, Bertrand R. Brinley’s The Mad Scientist’s Club, Robert McCloskey’s Homer Price, and especially Lester Del Rey’s The Runaway Robot… these were the books I devoured again and again as a child. And the ones that most shaped my future reading tastes, now that I look back on it.

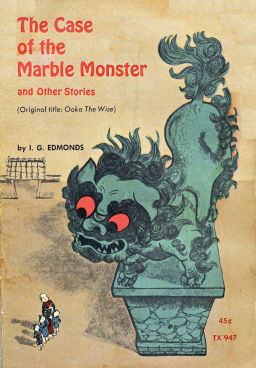

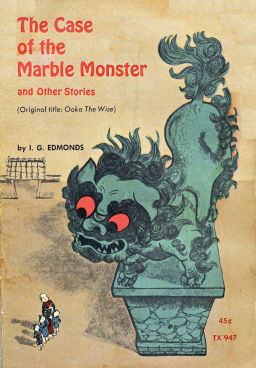

I’ve been able to interest all of my kids in at least one or two. And as you might expect, they disagree on which one is the best. The only one to receive universal praise is a thin collection of short stories originally published in 1961: I.G. Edmonds’s The Case of the Marble Monster.

The Case of the Marble Monster collects the tales of the legendary Judge Ooka, the 17th-century Japanese samurai in the service of the Tokugawa shogunate. Even if you’ve never heard of Ōoka Tadasuke, you’ve almost certainly heard of his cases, some of the most famous legal decisions in history. They include “The Case of the Stolen Smell,” in which an obnoxious innkeeper accuses a poor student of stealing the smell of his food, and ”The Case of the Bound Statue,” in which Ooka is asked to uncover the thief of a cartload of cloth, and he orders a statue of Jizo (a stone guardian) to be bound and arrested for dereliction of duty. All three of my children are in agreement that The Case of the Marble Monster is a fabulous book, and I can’t argue with their judgment. The tales have been passed down for hundreds of years, and it’s not hard to see why.

The Case of the Marble Monster was published by Scholastic Books in 1961. It was 45 cents in paperback for a slender 112 pages; you can buy copies on e-Bay for roughly ten times that. It’s well worth it.

This is one of the earlier issues after Astounding completed its name-change to Analog. (The issues from February through September 1960 showed both titles on the cover – so October 1960 was the first purely Analog issue.)

This is one of the earlier issues after Astounding completed its name-change to Analog. (The issues from February through September 1960 showed both titles on the cover – so October 1960 was the first purely Analog issue.)

A little while ago, Fearless Leader John O’Neill

A little while ago, Fearless Leader John O’Neill