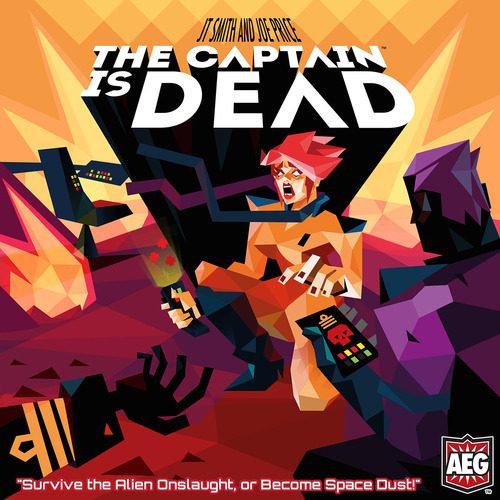

Board Game Review: The Captain Is Dead

Anyone else feel like we’re living in a Golden Age of board games? Or have I just been playing more because of COVID? We’re spoiled. Gone are the days of cutting out your own cardboard counters and coloring in your own dice with a crayon.

Anyone else feel like we’re living in a Golden Age of board games? Or have I just been playing more because of COVID? We’re spoiled. Gone are the days of cutting out your own cardboard counters and coloring in your own dice with a crayon.

What, none of you ever played Metagaming MicroGames? They were pretty great. I think Sticks and Stones was the first time I experienced a point-buy mechanic.

But enough GenX 80s nostalgia.

The latest in my personal quarantine parade of top-notch-in-every-respect board games is The Captain Is Dead from The Game Crafters (J.T. Smith and Joe Price) and AEG. I tried this game, originally developed on Kickstarter, with the kids the other night. Everyone had a raucous and exciting time. It’s one of those games you end up thinking about after the box is closed and put away. As a matter of fact, the kids are still talking about it two days later. It’s designed for 2-7 players, though after a couple sessions it seems to me there would be no effective difference if you wanted to solo play handling 2-7 crew yourself; no mechanics would need to be changed.

The premise is that you’re in a starship and have just suffered a massive, Wrath of Khan-style surprise attack from aliens out for a bit of the old ultra-violence. Multiple systems are down. Aliens are teleporting in to occupy the ship. The crew may be afflicted with strange disorders. But worst of all, the Captain is gone, crisped without so much as a “Kiss me, Hardy.”

You could say this game beings in medias res.

And if you don’t play tight and co-oppy, it’ll end there too.

You maneuver surviving officers and crewmen around the ship trying to restore function, with the overriding goal being getting the jump drive repaired so you can get the heck out of Dodge. And that’s the first of the many wonderful elements to this game, there are 18 characters to choose from, ranging from a fleet admiral down to a janitor (color-coded according to their role in the starship’s sub-systems, because cost-saving 60s TV production measures live on through the ages like military specs), each with unique abilities that I believe would combine to make this game highly replayable. There’s even an ensign, if for some reason you want the rest of your co-opers to constantly yell “Shut up, Wesley!” at you.

Day 9 of Fantasia began for me with The Block Island Sound. Directed by brothers Kevin and Matthew McManus, and written by Matthew, it’s a horror movie named for a body of water off the coast of Rhode Island. It’s the rare horror story that deals with inhuman mysteries on the northeastern coast of the United States while not feeling Lovecraftian at all.

Day 9 of Fantasia began for me with The Block Island Sound. Directed by brothers Kevin and Matthew McManus, and written by Matthew, it’s a horror movie named for a body of water off the coast of Rhode Island. It’s the rare horror story that deals with inhuman mysteries on the northeastern coast of the United States while not feeling Lovecraftian at all.

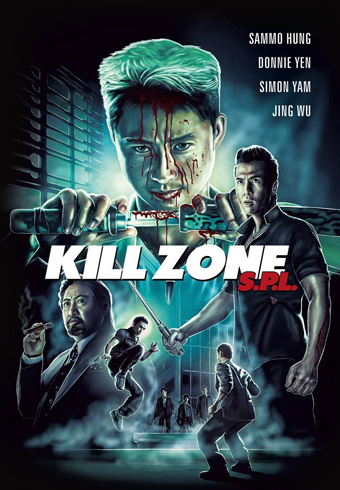

One of the lovely things about covering Fantasia is the chance to see genre classics I missed the first time around, often brought back to the screen in a restored version. Again in 2020, notwithstanding its streaming-only nature, Fantasia revived a number of great films from prior years. While my own inefficiency with scheduling meant I ended up missing Johnnie To’s A Hero Never Dies, I saw many of the others, including Wilson Yip’s 2005 movie SPL: Kill Zone (also just Kill Zone, originally SPL: Sha Po Lang, 殺破狼).

One of the lovely things about covering Fantasia is the chance to see genre classics I missed the first time around, often brought back to the screen in a restored version. Again in 2020, notwithstanding its streaming-only nature, Fantasia revived a number of great films from prior years. While my own inefficiency with scheduling meant I ended up missing Johnnie To’s A Hero Never Dies, I saw many of the others, including Wilson Yip’s 2005 movie SPL: Kill Zone (also just Kill Zone, originally SPL: Sha Po Lang, 殺破狼).

There is, or was, or might have been according to some, a movement in Greek cinema that started and flourished in the first half of the second decade of the twenty-first century called the Greek Weird Wave. This movement,

There is, or was, or might have been according to some, a movement in Greek cinema that started and flourished in the first half of the second decade of the twenty-first century called the Greek Weird Wave. This movement,