Rogue Blades Presents: Recalling a Fantasy Hero — Hanse Shadowspawn

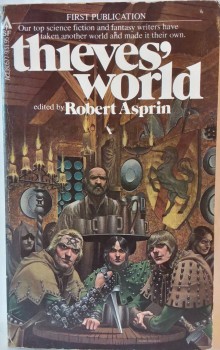

As I’ve written before, my introduction to Sword and Sorcery literature came not through the more traditional routes of Robert E. Howard, Fritz Leiber, Michael Moorcock, etc. I first delved into Sword and Sorcery almost by accident about 1979 when at the age of nine I picked up a collection of fantasy short stories titled Thieves’ World, the first in what eventually would become a long series of anthologies and novels and even gaming-related material.

As I’ve written before, my introduction to Sword and Sorcery literature came not through the more traditional routes of Robert E. Howard, Fritz Leiber, Michael Moorcock, etc. I first delved into Sword and Sorcery almost by accident about 1979 when at the age of nine I picked up a collection of fantasy short stories titled Thieves’ World, the first in what eventually would become a long series of anthologies and novels and even gaming-related material.

At that point in my young life I had discovered Tolkien, and I had read what was then the first of Terry Brooks’ Shannara books, but that was about the extent of my fantasy readings outside of comic books.

Thieves’ World opened my eyes to a much larger and somewhat darker potential for fantasy literature, one I had yet to envision at that time.

Yet my love for the series, and for Sword and Sorcery, would not come immediately upon opening the book. The introduction by series editor Robert Asprin proved interesting enough as did the first short story, “Sentences of Death” by John Brunner, and the following tales were also worthy reads.

Yet when I got to the fourth tale, “Shadowspawn” by Andrew Offutt, something … changed. Something opened within me.

This tale featured one Hanse Shadowspawn, a young, cocky thief who often wore bright garb by the day but dark garb by the night. And he also wore a dozen or so daggers about his body. Hanse showed himself to be a cocky, swaggering sort of fellow, though he also had a soft spot for those he loved.

Over the next forty or so years throughout multiple short stories and a few novels, Hanse Shadowspawn still remains one of my favorite fantasy characters. Despite his upbringing on the roughest streets of the city of Sanctuary, he became a friend to royalty, rescued a near-god from a fate worse than death, found love, grew old and learned his parentage consisted of … but that would be telling. I’ll try to leave more than a little mystery. Let’s just say, Hanse proved no mere thief, and he was the best at what he did for a reason, for several reasons.

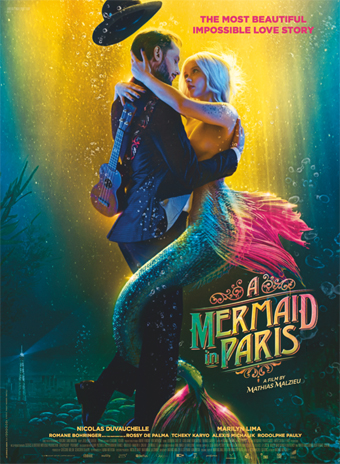

Back in my 2014, my first year covering the Fantasia Festival for Black Gate, I reviewed an animated movie called

Back in my 2014, my first year covering the Fantasia Festival for Black Gate, I reviewed an animated movie called

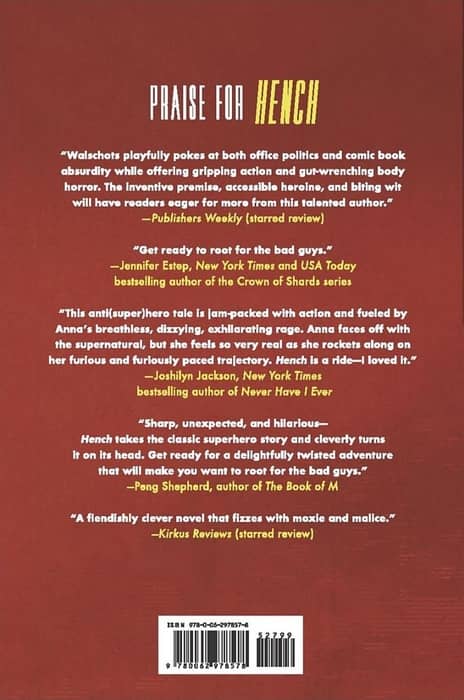

I try to keep an eye on comics, but like many people my first exposure to Pepe the Frog was as a poorly-drawn meme spouting racism. I remember reading about Pepe’s comics origin, but the name of Matt Furie, the cartoonist who created him, remained a piece of trivia. As did his comic Boy’s Club, where the frog first appeared. Now there’s a documentary telling the whole story of Furie, Pepe, and Boy’s Club — a tale of politics, appropriation, and how art can be used in ways the artist could not imagine, for worse and for better.

I try to keep an eye on comics, but like many people my first exposure to Pepe the Frog was as a poorly-drawn meme spouting racism. I remember reading about Pepe’s comics origin, but the name of Matt Furie, the cartoonist who created him, remained a piece of trivia. As did his comic Boy’s Club, where the frog first appeared. Now there’s a documentary telling the whole story of Furie, Pepe, and Boy’s Club — a tale of politics, appropriation, and how art can be used in ways the artist could not imagine, for worse and for better.

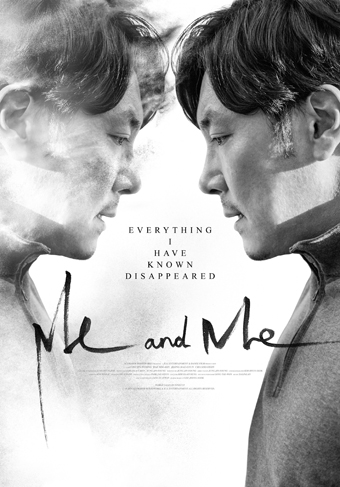

One of the genuinely wonderful things about covering a film festival is occasionally getting to be among the first audiences for a movie trying something new. That is, being an early viewer of a movie that does things unlike other movies, and getting to make one’s own mind up on whether those things work. Movies at a festival have often not had a critical consensus formed around them, and have not yet been defined by other writers or had their influences mapped out. You as the viewer are alone with the thing, almost contextless, in a way that’s rare these days.

One of the genuinely wonderful things about covering a film festival is occasionally getting to be among the first audiences for a movie trying something new. That is, being an early viewer of a movie that does things unlike other movies, and getting to make one’s own mind up on whether those things work. Movies at a festival have often not had a critical consensus formed around them, and have not yet been defined by other writers or had their influences mapped out. You as the viewer are alone with the thing, almost contextless, in a way that’s rare these days.

Consider if you will the high school story. By which I mean a story set at a high school, usually involving some members of the student body. It’s relatively unusual for these kinds of stories to be about actual academic achievement, or to put more than maybe one or two members of the faculty in the foreground. It happens, of course. But usually high school stories are about the students, and their lives and interactions, with classes and teachers and adults as external factors that can be used to shape the story but are ultimately incidental to it.

Consider if you will the high school story. By which I mean a story set at a high school, usually involving some members of the student body. It’s relatively unusual for these kinds of stories to be about actual academic achievement, or to put more than maybe one or two members of the faculty in the foreground. It happens, of course. But usually high school stories are about the students, and their lives and interactions, with classes and teachers and adults as external factors that can be used to shape the story but are ultimately incidental to it.