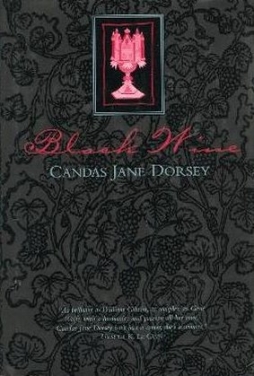

Candas Jane Dorsey and Black Wine

Some time ago, at one book fair or another, I took a chance on a book I’d never heard of: Black Wine by Candas Jane Dorsey. I’m not sure why; I’d already had reasonable luck at the sale, as I recall, so I didn’t feel the need (as one sometimes does) to grab a book for the sake of coming away with something. I don’t normally buy books based on cover art, and in any case this cover was more stylish than striking, a black pattern on black. It may have been the mention on the cover that the book had won an award for Best First Fantasy Novel. Most likely, it was the puff quotes on the back, featuring praise from Elisabeth Vonarburg and Ursula Le Guin (who compared Dorsey to Gene Wolfe). At any rate, buy it I did, for whatever reason; and having finally gotten around to reading it, I’m happy I went for it. Black Wine is an excellent, excellent book.

Some time ago, at one book fair or another, I took a chance on a book I’d never heard of: Black Wine by Candas Jane Dorsey. I’m not sure why; I’d already had reasonable luck at the sale, as I recall, so I didn’t feel the need (as one sometimes does) to grab a book for the sake of coming away with something. I don’t normally buy books based on cover art, and in any case this cover was more stylish than striking, a black pattern on black. It may have been the mention on the cover that the book had won an award for Best First Fantasy Novel. Most likely, it was the puff quotes on the back, featuring praise from Elisabeth Vonarburg and Ursula Le Guin (who compared Dorsey to Gene Wolfe). At any rate, buy it I did, for whatever reason; and having finally gotten around to reading it, I’m happy I went for it. Black Wine is an excellent, excellent book.

Published in 1997, it not only won the IAFA/Crawford Award for Best First Fantasy Novel, but also the James Tiptree, Jr. Award, and the Aurora Award for Best Long Form Work in English by a Canadian Science Fiction or Fantasy Writer. Dorsey herself (I find from Wikipedia and the ISFD) is a poet and prose writer from Edmonton. She’s published one other novel, A Paradigm of Earth, along with two collections of short fiction, and has edited and co-edited a number of anthologies. She also co-wrote a novel called Hardwired Angel with Nora Abercrombie.

Black Wine is a tricky book to describe. It begins by presenting three different narratives in three consecutive chapters; those narratives then coil back and forth. It’s not too difficult to work out how they interlock, but it does require careful attention and (in my case) considerable flipping around to re-read earlier parts. Further, names are powerful in this book, sometimes seeming to be guarded like treasures; which makes keeping track of characters and their family relations a challenge — particularly as so many of those characters are mother and daughter, a recurring relationship that seems to shape the story: the dominant narrative, we eventually realise, is set off by a daughter’s quest for her mother, a mother gone missing as a result of her relationship with her own mother and (especially) her mother’s mother.

Of Blood and Honey

Of Blood and Honey

Worldsoul

Worldsoul