Prologomenon to Fantasy

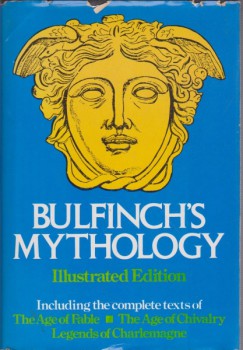

One of the things that I frequently blather about is that, when I was growing up in the 1970s, “fantasy,” as it’s understood today didn’t really exist, at least not as a mainstream, popular genre.

One of the things that I frequently blather about is that, when I was growing up in the 1970s, “fantasy,” as it’s understood today didn’t really exist, at least not as a mainstream, popular genre.

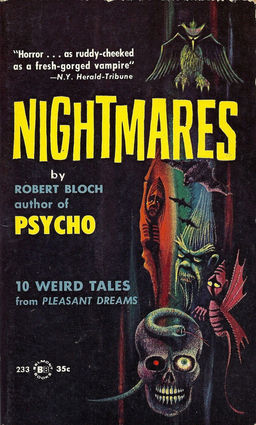

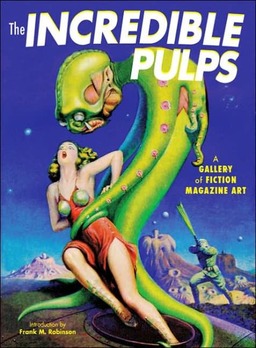

Don’t get me wrong: the ’70s were a decade of fantasy par excellence, especially literary fantasy, from reprintings of earlier works, such as the Lancer Books Conan series (begun in 1966) and the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series (begun in 1969), to the Tolkien imitators, like Terry Brooks’s The Sword of Shannara (1977) and Stephen R. Donaldson’s Lord Foul’s Bane (1977) – not to mention Tolkien’s own The Silmarillion (1977 once again!) – to modern classics like Fritz Leiber’s Our Lady of Darkness (guess what year?). The ’70s also saw fantasy rise to prominence in other media, like comic books, where Roy Thomas’s Savage Sword of Conan cultivated an entire generation of artists, and movies, where special effects artists continued to acquire the skills and technology to bring fantasy to life on the silver screen. And, of course, the decade also saw the appearance and flourishing of fantasy roleplaying games, beginning with Dungeons & Dragons in 1974.

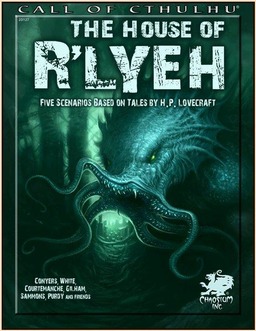

Despite these strides, spearheaded by the faddish popularity of D&D and its imitators, I’d argue that fantasy didn’t really come into its own as a pop cultural phenomenon until much later. Consequently, when I first encountered Dungeons & Dragons very late in 1979, I had almost no direct experience of what we’d nowadays call fantasy. Indeed, I wouldn’t read a word of The Lord of the Rings or the tales of Conan until after I’d begun rolling polyhedral dice. For that matter, I don’t think I’d even heard of J.R.R. Tolkien or Robert E. Howard until I encountered both their names in the pages of the J. Eric Holmes-edited D&D rulebook that was my introduction to the game. The same goes for Lovecraft, come to think of it, and most of the other authors whom we typically regard as the “founders” of fantasy. In that respect, my youth is very different than that of 21st century fantasy aficionados, almost all of whom I’d bet didn’t make it to the age of 10 without at least being familiar with the characters and ideas these authors birthed.

However, this isn’t to say I had no experience with fantasy before I discovered Dungeons & Dragons, only that my introduction to it was of a different sort, one I expect I shared with many kids of my generation.

There’s a certain kind of structure I’ve lately begun to notice in certain novels. These books read like puzzles, telling one story directly and overtly while implying a second story, or highly variant reading of the first story, through carefully-placed gaps, contradictions, and seemingly-irrelevant details. Throwaway references in highly-disparate points of the book might imply a completely different way to read at least the plot and often the tone or theme. It’s something Gene Wolfe does a lot; other examples I’ve noticed lately are

There’s a certain kind of structure I’ve lately begun to notice in certain novels. These books read like puzzles, telling one story directly and overtly while implying a second story, or highly variant reading of the first story, through carefully-placed gaps, contradictions, and seemingly-irrelevant details. Throwaway references in highly-disparate points of the book might imply a completely different way to read at least the plot and often the tone or theme. It’s something Gene Wolfe does a lot; other examples I’ve noticed lately are

My reading’s defined, largely, by sheer chance. I stumble across something at a used-book sale, buy it along with a box of other books, put it on my shelf and forget about it, then finally years later take it down and read it and, often, realise I should have started in on it long before. Which is a long way around to explaining how I just now came to read Chris Moriarty’s debut novel Spin State, which was published in 2003. And why I’m only now writing about the best work of 21st-century science fiction I personally have read.

My reading’s defined, largely, by sheer chance. I stumble across something at a used-book sale, buy it along with a box of other books, put it on my shelf and forget about it, then finally years later take it down and read it and, often, realise I should have started in on it long before. Which is a long way around to explaining how I just now came to read Chris Moriarty’s debut novel Spin State, which was published in 2003. And why I’m only now writing about the best work of 21st-century science fiction I personally have read.