Fantasia 2019, Day 16, Part 1: Night God

My first film on Friday, July 26, was a Kazakh work playing at the de Sève Cinema. Written and directed by Adilkhan Yerzhanov, Night God is a particular sort of uncompromising. It’s a beautiful picture, but extremely slow, still, and self-consciously meditative. I was deeply moved, for all its studied avoidance of simple dramatic action.

My first film on Friday, July 26, was a Kazakh work playing at the de Sève Cinema. Written and directed by Adilkhan Yerzhanov, Night God is a particular sort of uncompromising. It’s a beautiful picture, but extremely slow, still, and self-consciously meditative. I was deeply moved, for all its studied avoidance of simple dramatic action.

A man (Bajmurat Zhumanov), his wife, and his daughter (Aliya Yerzhanova) arrive in an unnamed town, a post-industrial city ruled by a cadre of state officers. It’s dark and cold, with comets in the sky, and the people live in fear of the coming of the Night God who will destroy the world. The man’s ordered to report to the local TV station to act as an extra, in exchange for which he’ll be given a house; this sets off a chain of serio-comic misadventures that must be called ‘kafkaesque’ if that word is to have any meaning.

A fake bomb’s strapped to his torso as part of a game show. But the bomb turns out to be real. He asks to have it removed. But before that he has to get an imam to sign a document attesting that he isn’t a radical. Thematically, then, there is a faith present in the film implicitly opposing the belief in the Night God; but all along the way the movie’s speaking of the struggle to believe in anything in a world that is feral and, to all appearances, meaningless.

The first thing one notices about the film is its intense visual beauty. It’s a mix of beautiful shadows and beautiful light. Taking place in an endless night, illumination is nevertheless powerful, bringing out colours and detail. We see every crack in every wall, every mote of dust; and this city is filled with cracks and dust. Although apparently shot entirely in studio, the town feels like a real place, looks like a real city coping with decayed industries and a collapse of central government. There are no screens or phones, and it feels right that a television station, the old technology of an earlier age, is central to the story.

That sheer sensory power is important, because the movie’s based mostly on very long takes with no or minimal camera moves. That is, the camera moves enough to give a very subtle sense of personality to the scene; not a sense of threat, as can happen with long tracking shots, but a kind of curious meditative feel, as though the camera is shifting ever-so-slowly to get a better idea of what’s happening. The soundtrack’s minimal, mostly a soundscape of whistling winds and water dripping from some unseen broken pipe. We’re stuck staring at what the movie insists on, and fortunately that is often beautiful in the way that inorganic decay and abandoned things can be beautiful. It has been said that the film has a painterly visual sensibility, and this is true. A statue, a clock without hands, a grated floor with light rising through it, come to feel like powerful statements hinting at a symbolism more profound than can be easily stated.

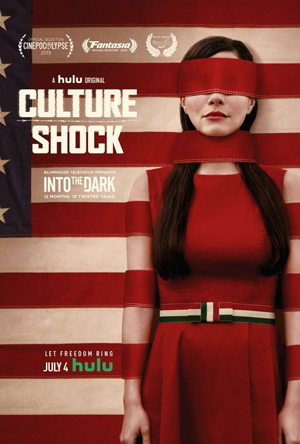

On June 25 I went to the De Sève Theatre for the one movie I’d see that day at the Concordia campus. It was called Culture Shock, and while it’s available on Hulu, this was a rare chance to see it in Canada.

On June 25 I went to the De Sève Theatre for the one movie I’d see that day at the Concordia campus. It was called Culture Shock, and while it’s available on Hulu, this was a rare chance to see it in Canada.

There was only one film I planned to watch on July 24, and that was writer-director Johannes Nyholm’s Koko-di Koko-da. It promised to be a strange movie about characters trying to break out of a time loop, and I settled in at the De Sève Theatre wondering at the horror elements implied by the film’s description in the festival catalogue.

There was only one film I planned to watch on July 24, and that was writer-director Johannes Nyholm’s Koko-di Koko-da. It promised to be a strange movie about characters trying to break out of a time loop, and I settled in at the De Sève Theatre wondering at the horror elements implied by the film’s description in the festival catalogue.

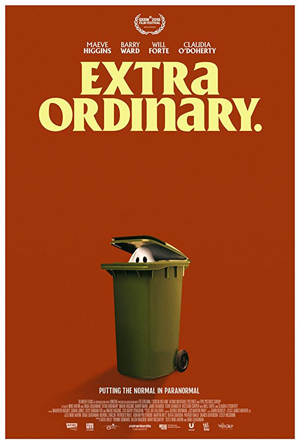

I had one film on my schedule for July 23, an Irish horror-themed comedy named Extra Ordinary. It was preceded by one of the best shorts I saw at Fantasia this year outside of a short film showcase.

I had one film on my schedule for July 23, an Irish horror-themed comedy named Extra Ordinary. It was preceded by one of the best shorts I saw at Fantasia this year outside of a short film showcase.