Fantasia 2019, Day 15: Culture Shock

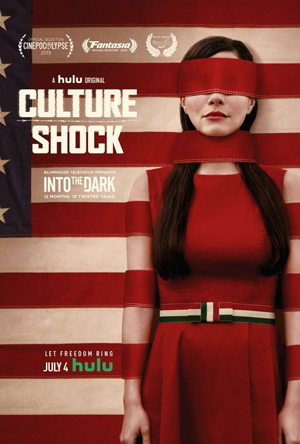

On June 25 I went to the De Sève Theatre for the one movie I’d see that day at the Concordia campus. It was called Culture Shock, and while it’s available on Hulu, this was a rare chance to see it in Canada.

On June 25 I went to the De Sève Theatre for the one movie I’d see that day at the Concordia campus. It was called Culture Shock, and while it’s available on Hulu, this was a rare chance to see it in Canada.

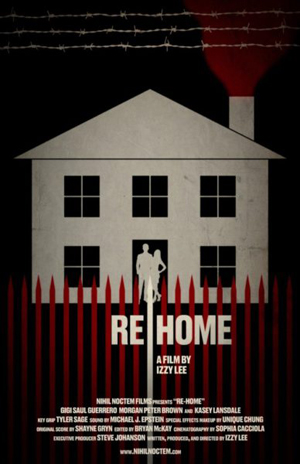

It was preceded by a short called “Re-Home,” directed by Izzy Lee. I’ll note for the record that I’m friends with the man who provided the music for the short, though I don’t think that affected my opinion one way or the other. In a future in which a wall along the southern border of the United States has been built, a poor Spanish-speaking woman (Gigi Saul Guerrero, director of Culture Shock) re-homes her baby, giving the child up for adoption to an Anglophone couple. But is something darker going on?

As usual at Fantasia, to ask that question is to get the answer “yes.” The short’s done well, with lots of atmosphere and style, but the twist at the end is the farthest thing from surprising. This feels like a piece of a larger story; either a beginning setting up something more complicated, or the ending of a tragedy that would have allowed us to be more invested in the mother and made her more individual. It’s highly watchable as it is, and certainly doesn’t overstay its welcome at only 8 minutes, but might actually be better served at a longer running time with more plot development.

Then came Culture Shock, which was made as an episode of Hulu’s horror anthology series Into the Dark. Each episode of the show is based on an American holiday, and this one was inspired by the Fourth of July. As noted, Culture Shock was directed by Gigi Saul Guerrero, who also worked on the script by James Benson and Efrén Hernández. She introduced the movie by noting it was a Blumhouse production, and saying that as an immigrant she felt she had a responsibility to tackle this material. She said she hopes it has something to say, and also provides an escape for 90 minutes.

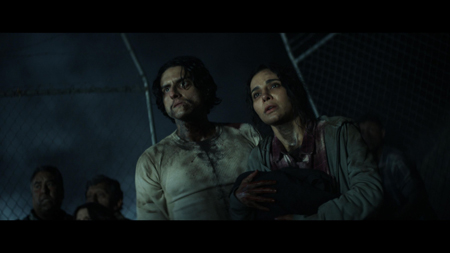

It follows Marisol (Martha Higareda, of Altered Carbon fame), a heavily pregnant Mexican woman desperate to cross into the United States and begin a new life in a country she sees as having more opportunities. A good part of the movie follows her difficulties finding her way northward, showing her challenges as a woman finding out who she can trust and who she can’t; it also establishes the stories of other would-be immigrants travelling with her. When they all reach the border, though, something strange happens. Marisol wakes up in an idyllic American small town out of the 1950s or early 60s, a place obviously unreal. What’s happened to her? And how can she get free of this weird red-white-and-blue image of domesticity?

In fact Marisol drifts in and out of this reality several times during the film, and one thing the movie does well is play with different levels of reality — one meaning of culture shock, I suppose. But more generally this is a film that establishes several different filmic realities. The Mexico of the opening scenes has an earthy verisimilitude to it, not just in the way it shows violence but also in the way, for example, Marisol talks about pregnancy with a group of other women. The trip to the border has a definite sense of physical danger, creating the tension of a suspense film. Then we’re hit with the surrealism of the village, a little like The Prisoner if it were set in a heightened version of America in 1963, a setting where you wait for Kennedy to get shot but where he never quite is. Which is to say that the genre shifts, and we’re in a different world in more ways than one.

In fact Marisol drifts in and out of this reality several times during the film, and one thing the movie does well is play with different levels of reality — one meaning of culture shock, I suppose. But more generally this is a film that establishes several different filmic realities. The Mexico of the opening scenes has an earthy verisimilitude to it, not just in the way it shows violence but also in the way, for example, Marisol talks about pregnancy with a group of other women. The trip to the border has a definite sense of physical danger, creating the tension of a suspense film. Then we’re hit with the surrealism of the village, a little like The Prisoner if it were set in a heightened version of America in 1963, a setting where you wait for Kennedy to get shot but where he never quite is. Which is to say that the genre shifts, and we’re in a different world in more ways than one.

The explanation behind the surreal village is not surprising in the slightest. That said, it has a few twists in how it plays out, specifically in having more stages than one might expect. In general, though, the plot’s relatively straightforward, if commendably centred on Marisol. This is a movie that knows what story it’s telling and tells it with solid craft, doing a clever job of finding occasions to set up plot points without having those occasions feel like they’re doing set-up work. Worth noting that the performances are very fine, with Higareda in particular much stronger than she was in Altered Carbon.

Still, for a variety of reasons, I wasn’t too convinced by the explanation behind the illusion of America. It shouldn’t be surprising that the village is linked to the American government, but I am very much afraid that reality has outstripped horror in some ways. It is possible to imagine an explanation for the elaborateness of the village and the resources involved by imagining, say, a backstory of corruption, of a project given funding so that various hands at various stages could skim money. This would also explain a more minor plot issue, which is that at key moments the bad guys do not have the kind of security manpower they reality ought to have. But it’s not an explanation the film suggests, and on its face the village feels to me as a cynical Canadian out-of-true with what the American government’s actually doing.

These things are perhaps ultimately beside the point. Marisol’s character is the thematic centre of the film, and specifically her perspective on America and on her homeland. She changes in the small-town reality, as she must, and both the things to which the reacts and the ways in which she reacts to them feel like the right things to produce the change we see. In particular, as the small town builds toward a celebration of the Fourth of July, Marisol’s reaction to the holiday is engagingly uncompromising. The film manages to avoid nationalism while still bringing out her pride in her background; that is to say she grows over the course of the movie, engaging with her idea of home in a complex way.

These things are perhaps ultimately beside the point. Marisol’s character is the thematic centre of the film, and specifically her perspective on America and on her homeland. She changes in the small-town reality, as she must, and both the things to which the reacts and the ways in which she reacts to them feel like the right things to produce the change we see. In particular, as the small town builds toward a celebration of the Fourth of July, Marisol’s reaction to the holiday is engagingly uncompromising. The film manages to avoid nationalism while still bringing out her pride in her background; that is to say she grows over the course of the movie, engaging with her idea of home in a complex way.

Meanwhile, the virtual America is an appropriate metaphor for the image of America projected by America. I don’t know how much people in the United States appreciate it, but the way in which American culture talks about America is often unreal. It’s difficult, in fact, to know sometimes whether Americans telling stories about America understand how unreal it is. This may well be true for every country, but the scale of media in the United States brings it to another level. All of which is to say that there’s a false image of the country, a dream image, that perhaps Americans know to be an aspiration but which is sometimes presented as reality.

Marisol’s bought into that dream as the film begins. What happens over the course of the story necessarily challenges that, and that makes this story a story about a character who must re-examine what they believed to be true and what they thought they always wanted. Ultimately that in turn gives the story a heart that propels it through a basic concept that might seem familiar.

Oddly for a genre film, there’s a sense where the interest briefly fades when the genre elements are introduced. Marisol’s journey in the real world is interesting enough that the swerve into more fantastic territory feels at first like a slackening-off of tension. But the movie picks up again, as the weird new reality Marisol finds herself in acquires its own tension, and as we begin to see how it links up to the world we understand as real. Again, it’s Marisol’s character, her own confusion at finding herself in a strange land, that helps guide the audience through the hairpin turn in the story.

Oddly for a genre film, there’s a sense where the interest briefly fades when the genre elements are introduced. Marisol’s journey in the real world is interesting enough that the swerve into more fantastic territory feels at first like a slackening-off of tension. But the movie picks up again, as the weird new reality Marisol finds herself in acquires its own tension, and as we begin to see how it links up to the world we understand as real. Again, it’s Marisol’s character, her own confusion at finding herself in a strange land, that helps guide the audience through the hairpin turn in the story.

Culture Shock is a solid film that does what it wants, elevated in particular by a sense of realism in its opening scenes and by solid craft throughout. It doesn’t shy away from violence — to put it mildly — and effectively deploys suspense to keep the audience engaged. I can’t call it especially subtle or surprising, but it’s paced and shot with energy and passion. The ending’s satisfying, even if certain things come easily. It’s a good fun genre film that’s thought about right and wrong and the humanity of its characters. Which is about all you can ask for.

After the screening, director Gigi Saul Guerrero took questions. Asked how she pitched her involvement to Blumhouse Productions, she said (according to my unreliable notes) that after signing with her current agents a year ago she had a meeting with Blumhouse, who was looking for a director for their border-crossing feature. hey were interested by a short she had made, and so called back after the meeting. She pitched her vision of the film four times promising them she’d bring a lot of layers and that “I’ll make it so Mexa.” She remembered that after being confirmed for the film, she freaked out in Blumhouse Productions’ bathroom.

Asked if it was easy to shoot in Spanish, she said her crew trusted her, and she was happy with the decision. Asked about the patriarchal conditioning the movie shows in both Mexico and the United States, she spoke about the layers to the lead and how many elements the character had. She said she wanted a Hispanic point of view, but didn’t want to simply say the United States was bad and Mexico good. So it was important to her to show how scary Mexico can be for a woman. Asked about working with Barbara Crampton, a character actor who has a part in Culture Shock and a long body of work in horror and television, Guerrero said she freaked out everyone by always being in character, and was tremendous fun to work with.

Asked if it was easy to shoot in Spanish, she said her crew trusted her, and she was happy with the decision. Asked about the patriarchal conditioning the movie shows in both Mexico and the United States, she spoke about the layers to the lead and how many elements the character had. She said she wanted a Hispanic point of view, but didn’t want to simply say the United States was bad and Mexico good. So it was important to her to show how scary Mexico can be for a woman. Asked about working with Barbara Crampton, a character actor who has a part in Culture Shock and a long body of work in horror and television, Guerrero said she freaked out everyone by always being in character, and was tremendous fun to work with.

Asked about Higareda’s work, Guerrero said she was known in Mexico for romantic comedies, and not having seen Altered Carbon she’d been unsure of her for the part of Marisol. She brought her in, chatted about Mexico and other things not directly related to the film, and they connected to the point that on set they didn’t need to communicate in words. Asked further about shooting in Spanish, she said it wasn’t planned, but everybody had fun and felt part of it. The next question noted that the film had been airing since July on Hulu and asked about its reception. Guerrero said it was very positive, and noted it was at 100% on Rotten Tomatoes (which as of this writing it still is). She said there were some Trump supporters against the movie and her personally, leading to the sending her some “out-there” tweets. She said she responded by trolling back.

To a question about the art direction of the movie, particularly in the fictional village, she said her direction was to create an atmosphere of ‘Pleasantville gone wrong’ and everyone got it. She spoke about putting up war propaganda pictures to give an idea of what she wanted. The scenes in the real world had to be as gritty as possible to make a contrast. She noted that she wasn’t working with her usual crew, and said they had to learn the “Gigi code” of more blood, more dirt. Asked if Blumhouse had asked her back to do more work, she said they’ve approached her to do other things she can’t talk about.

An emotional question came from an audience member who said he’d been born in El Salvador, and how looking at the movie and the characters made him want now to reconnect with his home. Guerrero said it was important to her to write real experiences into the film, and to have one of the immigrant characters not be a Mexican. Asked about a scene in Mexico with Marisol in a group of pregnant women learning about the process of pregnancy, she noted that it was something based on reality that she fought to keep in the script, and that it was tough to shoot.

Asked if she thought about how the movie would be received while shooting it, she said she thought about it every day. The movie was shot before news about people being kept in cages became public. She was nervous, doubting herself and how it would be received. She was inspired by Get Out, which she saw as inspired by frustration, and that helped her to keep going: regardless of the reception the film would get, the horror is there.

Asked how much the script was hers, she said quite a bit changed as she worked on the film, though the explanation for the unreal town was always there and was in fact what caught her eye. A number of critical characters and character-oriented sub-plots were added. Aspects of escape and revenge were also added, which were important for her. But in the end, she feels the heart of the original script is still in the finished film.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

“I don’t know how much people in the United States appreciate it, but the way in which American culture talks about America is often unreal. It’s difficult, in fact, to know sometimes whether Americans telling stories about America understand how unreal it is.”

As an American…

These are very legitimate remarks (and concerns). The underlying problem stems from one’s definition of “American” (and, even, “America”, vis-a-vis the United States thereof). As you know from your own observation, even two people who can be well described as having similar academic and intellectual back-grounds will disagree on a fundamental point about the US (that one being, as you likely recall, on whether or not the country is “Evil”).

“Culture Shock” played for me very much, I suspect, as it played for you. But I am a different from many of my countrymen. (Much as I am very similar to Other countrymen of mine.) I fear the ultimate problem with movies like “Culture Shock”, and the mentality they represent, is that it’s close to inconceivable that they could bridge a gap or begin a dialogue with those who disagree with its message and tenor.

It was a very good genre film, but as an American who is aware of the tenuous grasp our officially projected image has with reality (and even going so far as to think that the projected image is rather problematic) it’s easy for me to acknowledge that. Unlike certain Connecticut-based film teachers, I firmly believe — indeed, I must believe — that as a nation We Can Do Better.

But that is only one camp.

Thanks for posting this; I was a bit worried what I wrote might be read as an unneeded swipe.

I suspect you’re right about the movie not opening a dialogue with everyone. But then no movie’s for everybody. If every movie starts being all one thing or all another, then I suppose there could be a problem. (Up to a point. I mean, I see no difficulty if every movie takes as a starting point ‘Nazis are there for good guys to shoot.’)

I don’t know. Like I say, maybe every country has an image of itself that its people take to be true without realising how much it’s a fantasy. But I think all a storyteller can do in the face of that is try to tell the best story they can, you know?

You seem like a guy who doesn’t shy away from a long-ish read. This article: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/sep/03/the-myth-of-the-free-speech-crisis addresses one of the points we’re sort of talking around in a thorough and intelligent manner.

More playfully, I really want the next Democratic candidate’s campaign song to convey the ideal (and I’d underline that if I knew how to in this comment box) I’d like the US to adopt:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yHyryt1L79Y

Ironically, the video link goes to a video that’s not available in my country. (Found the song elsewhere, read the lyrics, and I think you might have a shot because it’s upbeat and the lyrics are ironic enough anybody can find a way to support them.)

The article’s really interesting. I’ve noticed some of what the writer’s talking about in the decline of online discourse, and wondered if it was just me, or the influence of social media radicalising people. So it’s fascinating to see the argument that the mainstream validates and perhaps caused the problem by allowing for dialogue that should not have happened. It makes sense. Although as you say it does sharpen the question of how to maintain any dialogue in this environment.