Fantasia 2020, Part XXII: The Block Island Sound

Day 9 of Fantasia began for me with The Block Island Sound. Directed by brothers Kevin and Matthew McManus, and written by Matthew, it’s a horror movie named for a body of water off the coast of Rhode Island. It’s the rare horror story that deals with inhuman mysteries on the northeastern coast of the United States while not feeling Lovecraftian at all.

Day 9 of Fantasia began for me with The Block Island Sound. Directed by brothers Kevin and Matthew McManus, and written by Matthew, it’s a horror movie named for a body of water off the coast of Rhode Island. It’s the rare horror story that deals with inhuman mysteries on the northeastern coast of the United States while not feeling Lovecraftian at all.

The plot revolves around a family native to Block Island, where a small community largely of fisherfolk lives year-round, tripling in size in the summer tourist season. It is not summer as the film opens, and an old fisherman named Tom Lynch (Neville Archambault) is beginning to act very strangely. Tom’s adult son Harry (Chris Sheffield), who lives with him, is getting worried. Coincidentally, when a mass of dead fish washes ashore on the island, Harry’s sister Audry (Michaela McManus), who has moved away from Block Island, is sent by her bosses at the EPA to investigate. Accompanying Audry is her subordinate Paul (Ryan O’Flanagan) and her young daughter Emily (Matilda Lawler). They stay at the family home as they investigate, and things become more and more unreal.

If the story’s about family, so’s the production; Michaela McManus is the sister of Kevin and Matthew, while in a Q&A after the film Sheffield described himself as an unofficial third McManus brother. At any rate the focus of the narrative is clearly on the Lynch family, as they reunite with plenty of long-held arguments still between them. Tom’s a hothead, who, as Audry percipiently observes, is always looking for someone to blame. Audry for her part is conscious of having left Block Island for another life, and is not especially happy to be back. And then there’s Tom, who may be slowly losing his faculties. Or may have something more disturbing afflicting him.

The movie’s not Lovecraftian, as I say, in part because it’s centred so intensely on the dynamic of the family — an emotional landscape utterly unlike anything in Lovecraft. It’s also far more class-conscious than Lovecraft, or at least conscious in a completely different way. If Audry’s vaguely like the academics who come to a small New England town to investigate some disturbing goings-on, her role in the story becomes something quite different: she’s involved, in ways Lovecraftian academics aren’t.

Worth noting that the look and feel of the film is also different from the twice-told narrative frame-structures of so much of Lovecraft. There’s an almost tactile sense to the film, a visual precision and a detailed soundscape — the washing of waves, the hush of wind — that between them convey a deep sense of place. That place has an atmosphere born not of isolation, though one does get that from the bare trees and the grey ocean, but of lives hard-lived. Tom’s home feels like the real home of a real person, living and working in a small town. The location of Block Island itself is shot such that it comes alive as a lived place, not defined in terms of its institutions so much as in the context for the lives and histories of the main characters. You believe that these people grew up here.

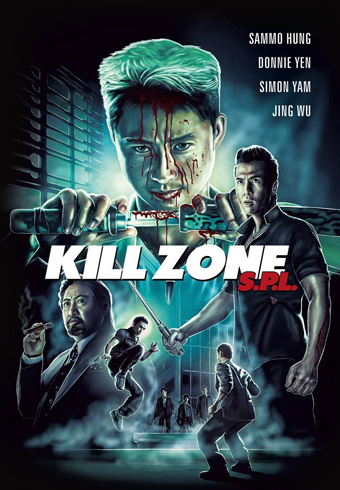

One of the lovely things about covering Fantasia is the chance to see genre classics I missed the first time around, often brought back to the screen in a restored version. Again in 2020, notwithstanding its streaming-only nature, Fantasia revived a number of great films from prior years. While my own inefficiency with scheduling meant I ended up missing Johnnie To’s A Hero Never Dies, I saw many of the others, including Wilson Yip’s 2005 movie SPL: Kill Zone (also just Kill Zone, originally SPL: Sha Po Lang, 殺破狼).

One of the lovely things about covering Fantasia is the chance to see genre classics I missed the first time around, often brought back to the screen in a restored version. Again in 2020, notwithstanding its streaming-only nature, Fantasia revived a number of great films from prior years. While my own inefficiency with scheduling meant I ended up missing Johnnie To’s A Hero Never Dies, I saw many of the others, including Wilson Yip’s 2005 movie SPL: Kill Zone (also just Kill Zone, originally SPL: Sha Po Lang, 殺破狼).

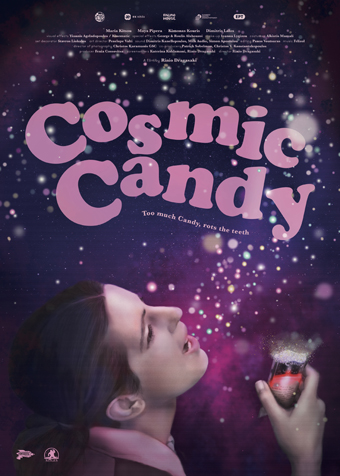

There is, or was, or might have been according to some, a movement in Greek cinema that started and flourished in the first half of the second decade of the twenty-first century called the Greek Weird Wave. This movement,

There is, or was, or might have been according to some, a movement in Greek cinema that started and flourished in the first half of the second decade of the twenty-first century called the Greek Weird Wave. This movement,