Monsters, Magic, and Kung fu: The Daoshi Chronicles by M. H. Boroson

|

|

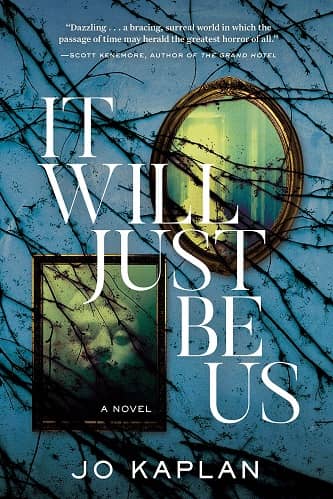

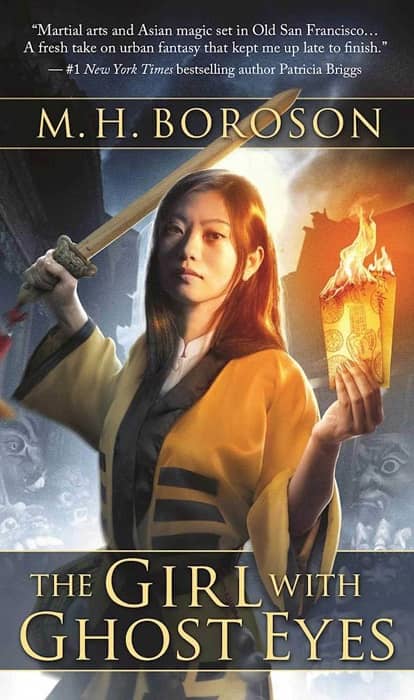

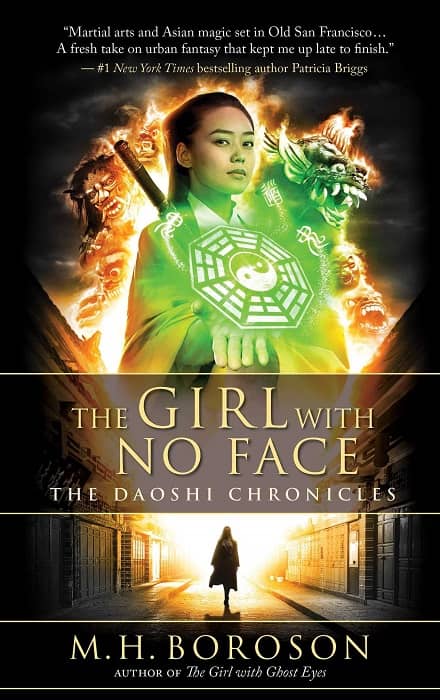

The Daoshi Chronicles, published in paperback by Talos Press. Covers by Jeff Chapman

I discovered M. H. Boroson’s delightful Daoshi Chronicles when Sarah Avery reviewed the opening novel The Girl With Ghost Eyes here at Black Gate five years ago, saying in part:

We’re connoisseurs of kickass combat scenes, eldritch lore, and victories won at terrible, unpredictable price. We want our heroes unabashedly heroic and morally complicated at the same time. Add a decade or more of research on the author’s part, distilled to the most concentrated and carefully placed drops, and a well-timed sense of humor, and you’ve got the recipe for the perfect Black Gate book…

Li-lin’s family has protected the world of the living from the spirit world for generations. Most Daoist priests and priestesses take it on faith that their rituals work — they can’t literally see the spirit world and the efficacy of their magic. Li-lin can, though. She has yin eyes, ghost eyes, a visionary ability that appalls her father and would disgust her trusting neighbors if they knew…

Devoted daughter, faithful widow, compassionate protector of Chinatown, Li-lin must conceal her rarest talent, lest she shame everyone she loves. Long practice at concealment, combined with the necessity of bending rules and stories if she’s to be effective in a world where even a warrior priestess is expected to show deference to men and elders no matter what, has prepared her almost too well for the mystery she must solve.

Someone wants her father dead. That someone wants it enough to lay trap after trap for her family. Bad magic is on its way, of the kind only the Maoshan can stop.

Li-Lin and her ghost eyes save Chinatown, don’t you doubt it.

The Girl With Ghost Eyes proved popular in broader circles as well. Publishers Weekly called it “A brilliant tale of monsters, magic, and kung fu in the San Francisco Chinatown of 1898,” and The A.V. Club proclaimed it a compelling page-turner, saying it “Introduces a thrilling world of kung fu, sorcery, and spirits… The pace never slows, offering a constant stream of strange characters, dire threats, and heroic actions.”

I had to wait for the paperback of the sequel, but Talos released The Girl With No Face in mass market in September and now I finally have a matching set.