The “Saw-the-Story-in-Half” Trick

(I passed the 50,000-word mark in National Novel Writing Month yesterday, at Day 14. Last year I achieved this at Day 13—I must be getting slow.)

(I passed the 50,000-word mark in National Novel Writing Month yesterday, at Day 14. Last year I achieved this at Day 13—I must be getting slow.)

I have started to view Frederick Faust as something of my writing mentor. He wasn’t a public figure, instead disguised behind “Max Brand” and his many other pseudonyms, but his excellent storytelling skill is a good teacher all on its own. However, in his letters he left behind some excellent advice about how he developed his ideas. Considering his productivity, which shames about every author in history through its sheer volume, he must have got his ideas fast.

It is easy to call Frederick Faust and other writers with enormous bibliographies to their credit (Andre Norton comes to mind immediately within speculative fiction) as “natural storytellers.” But I wonder how much that takes away from their efforts. Faust’s own notes about his writing indicate a man always on the search for “story,” and not simply plunking down in front of the typewriter and trusting to luck. Early in his career, Faust was constantly worried that each idea he had would be the last one he would ever find—and I think most writers would admit to a similar fear. But Faust discovered, “You spot stories in the air, flying out of conversations, out of books.”

Here’s a remarkable piece of advice I discovered in one of Faust’s letters, which offers an interesting writing exercise: “When you read a story, pause halfway through; finish the story in detail in your imagination; write it down in brief notes. Then read the story through to the end. Often you find that you have a totally new final half of a story. Fit in a new beginning and there you are.”

That so simple it’s beautiful. I’ve tried it a number of times, usually on modern works, and always come up with a sketch of something completely new. So far, I’ve never used one of these outlines to complete a full story, but a few other ideas have come out of this brainstorming.

While other magazines are dying (and then, a la

While other magazines are dying (and then, a la

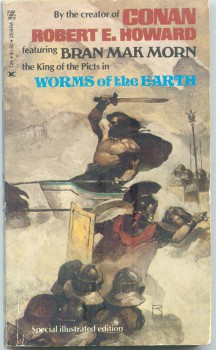

“Worms of the earth, back into your holes and burrows! Ye foul the air and leave on the clean earth the slime of the serpents ye have become! Gonar was right—there are shapes too foul to use even against Rome!”

“Worms of the earth, back into your holes and burrows! Ye foul the air and leave on the clean earth the slime of the serpents ye have become! Gonar was right—there are shapes too foul to use even against Rome!”