With a (Black) Gat: George Harmon Coxe

(Gat — Prohibition Era term for a gun. Shortened version of Gatling Gun)

(Gat — Prohibition Era term for a gun. Shortened version of Gatling Gun)

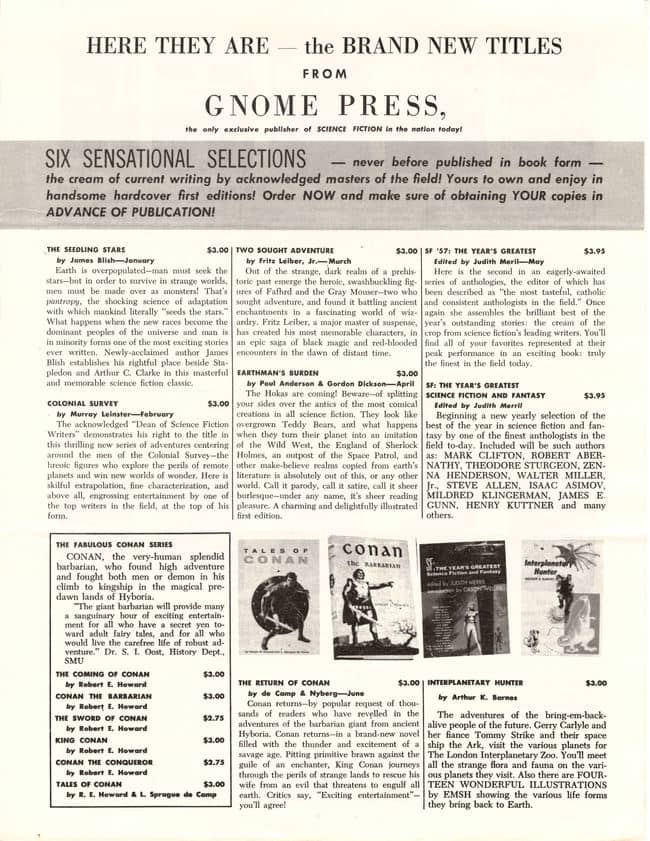

Working from Otto Penzler’s massive The Black Lizard Big Book of Pulps, we’re going to be exploring some pulp era writers and stories from the twenties through the forties. There will also be many references to its companion book, The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories. I really received my education in the hardboiled genre from the Black Lizard/Vintage line. I discovered Chester Himes, Steve Fisher, Paul Cain, Thompson and more.

With first, the advent of small press imprints, then the explosion of digital publishing, pulp-era fiction has undergone a renaissance. Authors from Frederick Nebel to Raoul Whitfield; from Carroll John Daly to Paul Cain (that’s 27 letters – we went all the way back around the alphabet – get it?) are accessible again. Out of print and difficult-to-find stories and novels have made their way back to avid readers.

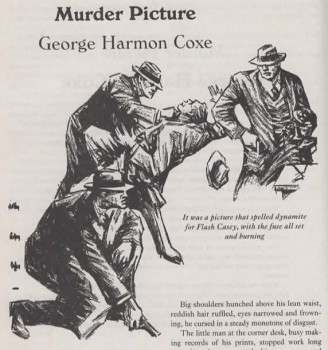

Strangely, George Harmon Coxe, one of the Black Mask boys, has been elusive in this pulp rebirth. He had a half-dozen recurring characters and wrote over sixty novels and his stories were also adapted for movies, television and radio. But it’s tough to find even a handful of his works these days, though a few novels have found their way to ebook format.

From 1935 to 1973, Coxe wrote twenty-three novels featuring Kent Murdock. Murdock, a Boston-area crime photographer, is really an evolved (make it, more refined and mature) version of an earlier Coxe creation, (Jack) Flashgun Casey. It’s a Casey story that’s in The Big Book and our focus today.

The photographer appeared two dozen times in Black Mask from 1934 through 1943. And there were six novels (one of which was previously serialized in Black Mask). But Casey fell by the wayside for the ‘cleaned up version’ that was Murdock. The Casey story, “Murder Mixup” was included in Joseph ‘Cap’ Shaw’s legendary Hard Boiled Omnibus — though it was one of three stories dropped when the paperback from Pocket Books came out.