To Roam the Unreadable Tome: The Night Land Straight Up

Anytime that you read a Black Gate article, you do so at your peril. We all know this. How much time and money have you spent tracking down obscure books that you’ve read about here, and how many irreplaceable hours have you spent reading them? Yeah. Me too.

My most recent bout of this fever I blame squarely on Nick Ozment, who recently blew a loud horn on behalf of William Hope Hodgson’s 1912 weird classic The Night Land. Now I’ve had a copy of this book on my shelf for thirty five years and never once come close to reading it. (Wife and kids, working for a living, eating and sleeping, reading a zillion other books, watching Lost and Breaking Bad — you know how it goes, Hodgson, old boy; it was nothing personal.) I never felt any guilt over neglecting this masterpiece; after all, in his article, Nick alluded to the book’s virtual unreadability in its original form (Mr. O was using his piece to boost James Stoddard’s 2010 “translation” of the book into a more modern, accessible idiom.)

Well, to tell me that a book is “difficult” or “impenetrable” or “practically unreadable” (all words that featured prominently in Nick’s article) is like waving a red flag at a bull. My reading fate for the next three weeks was decided at that moment.

[Click the images for Night Land-sized versions.]

The Night Land‘s reputation for being a tough row to hoe is well established. No less an authority than H.P. Lovecraft, in his 1927 essay Supernatural Horror in Literature, said that Hodgson’s story

is told in a rather clumsy fashion, as the dreams of a man of the seventeenth century, whose mind merges with its own future incarnation; and is seriously marred by painful verboseness, repetitiousness, artificial and nauseously sticky romantic sentimentality, and an attempt at archaic language even more grotesque and absurd than that in (Hodgson’s) Glen Carrig.

Ouch. When Howlin’ Howard talks about painful verboseness and grotesque and artificial language, he knows whereof he speaks.

H.P. Lovecraft

But Lovecraft also praised the book as an unparalleled masterpiece of exotic imagery and bold imagination. (He’s joined in this judgment by such luminaries as C.S. Lewis, Clark Ashton Smith, and Lin Carter.) Well, which is it — unreadable or essential? Or which is it mostly?

After journeying through The Night Land (Hodgson’s original, unabridged and unmodified), I can say that it contains 200 of the most extraordinarily vivid, eerily effective pages I’ve ever read. The only problem is that my copy of the book is 419 pages long.

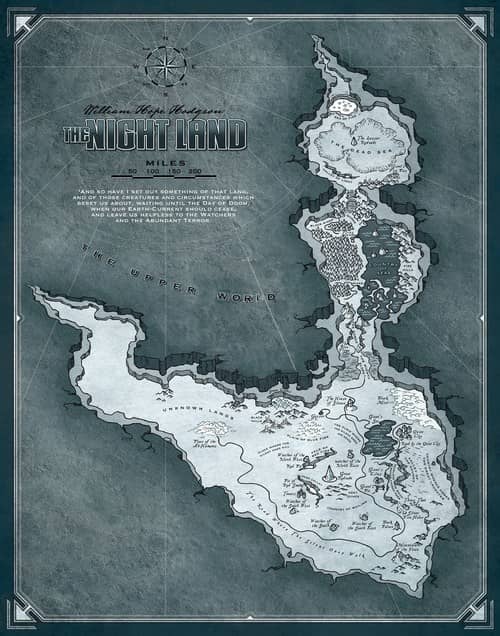

Dual-consciousness reincarnation aside, the story is relatively simple. Our man of the past/future, living uncounted millions of years after the death of the sun, leaves the enormous pyramidal redoubt that houses almost all that is left of humanity to venture forth across the dark world in search of his love. She dwells in a second refuge that contains a much smaller number of people; the two lovers are bound together by a kind of psychic link. (She’s reincarnated too, though she doesn’t know it.) It is this spiritual connection that will enable our unnamed hero to find his way through the blackness and reach his unseen goal.

After many trials and dangers he reaches his Lady Love (or the Maid as he calls her) at literally the last minute. The evil, misshapen things that live in the eternal midnight have very recently breached the Lesser Redoubt’s defenses and our hero is just able to get the Maid away. The pair then journey back to the safety of the Great Redoubt. That’s it. In essence, The Night Land is a straightforward “there and back again” quest story — virtually an Arthurian one, even to our hero’s wearing of armor and bearing a consecrated weapon, to say nothing of his goal of rescuing an endangered Lady Fair.

As such, the tale breaks neatly into two parts, and for me at least, one part works beautifully and one part fails disastrously. In the first half of the book, our narrator’s description of his strange world and his perilous journey through it are poetic, melancholy, macabre, bizarre, amazingly suggestive — the dark images and the solemn mood they engender strike the deep note of cosmic awesomeness that Lovecraft so prized and that so few writers can convincingly bring off.

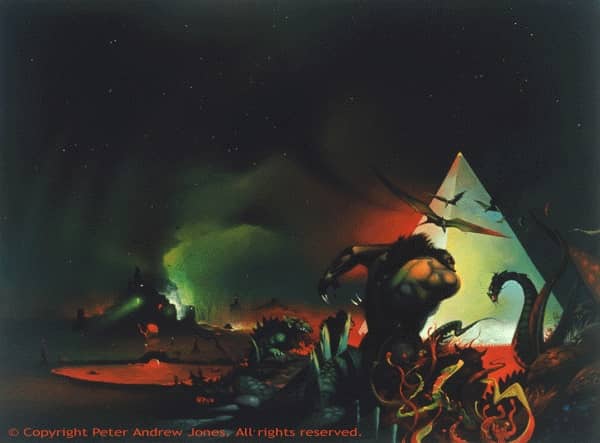

The narrator’s great pyramid is under siege; it is surrounded by evil things and enigmatic entities that Hodgson fills with mystery and menace by stressing their stillness and their silence. (And their size — many of The Night Land‘s denizens are literally giants, and the juxtaposition of malign and inscrutable consciousness with colossal size and perfect stillness is striking and deeply disquieting.)

Hodgson doesn’t describe things so much as name them: the House of Silence (which has endured unchanged for untold ages: blazing with light, utterly silent, and those who enter it never emerge), the Road where the Silent Ones Walk, the Plain of Blue Fire, the Country Whence Comes the Great Laughter, the Watcher of the South (“A million years gone, as I have told, it came from out of the blackness of the South, and grew steadily nearer through twenty thousand years; but so slow that in no one year could a man perceive that it had moved”) and many others abound in the region of humanity’s final refuge.

|

|

The Stoddard Retelling

The cumulative effect of these poetically named places and the eerie things that dwell in them is to evoke a corresponding awe and stillness and sense of dark expectancy in the reader, in a fashion quite unlike that produced by anything else I’ve ever read.

Beyond the immediate vicinity of the pyramid, the darkness is filled with creatures no less menacing, but seemingly more “natural,” like snakes and enormous slugs and dog-sized scorpions. Hodgson implies a distinction — never explicitly stated — between the ordinary biological results of millions of years of normal evolution (or even devolution — some of the dwellers of the night seem to be degenerate forms of humanity) and the kinds of extraordinary entities that congregate around the Great Redoubt, things that may have come from somewhere “outside.” (At one point the narrator travels through a region of portals in the black sky, openings that may connect to other dimensions.)

Hodgson’s vision of the far future may not turn out to be very accurate (though who can tell?), but if we narrow the frame to say, five years, he proved a kind of prophet. It’s hard to read of the narrator’s journey across an alien, shattered landscape lit by the hellish glare of sulfur spewing “fire holes,” with the air reeking of toxic gasses, threatened every moment by the possibility of sudden, violent death, and not think of the nightmare reality that Hodgson experienced just a few years later when he served on the Western Front during World War One, where he was killed by an artillery shell in April 1918, just seven months before the conflict’s end.

The real Night Land

I’m no expert on seventeenth century English diction, so I can’t judge whether Hodgson’s faux-archaic prose is inept or not, in the technical sense of accurately reproducing the language of John Bunyan and Oliver Cromwell. But it seems to me that in this first half of the book, the diction, stilted though it is, is effective in that it serves to highlight the pure strangeness of this extraordinary world. Who knows how a man of the far future will speak? Not like we do, certainly — or like a man of 1912, either. Using a voice from hundreds of years out of the past to convey depths of time strikes me as a reasonable solution to the problem, and for all the difficulties it causes (and it does), it arguably works better than a purely contemporary voice would have.

This holds true until the hero finds the Maid, about halfway through the book. At that instant the language ceases to be a virtue and is instead transformed into a ten-ton millstone around The Night Land‘s neck. Lovecraft’s criticisms then gain full force — “painful verboseness, repetitiousness, artificial and nauseously sticky romantic sentimentality” — HPL’s description is harsh but accurate. The journey back is filled with little else, as page after dreary page stretches before you, each awful, leaden paragraph like an endless mile on the Bataan Death March.

Part of the problem is structural — though Hodgson provides what incidental variation he can during the return journey, we’ve literally been here before, having already traversed this territory on our way to the Maid. The greater difficulty, though, is the Maid herself. Her presence provides the narrator endless opportunities to dive headlong into such rhapsodies as this:

And surely, when that I had her to my likings, I stept back a little pace; and lookt at her. And she to look again at me, very quaint and naughty; and then to turn her about, very grave; and to make pretend that she did be a dummy figure. And, surely, when she did be come right round, and to face me again, and had a very sedate look, she stretched out her pretty foot, all in a moment, and put her pink toes sudden upon my lips; and I to be so in surprise, that I had not wit to do aught, ere that she had them back swift from me. And she then to make one glad spring into mine arms, and to want that she be hugged, and to be loved very great. And I to laugh, all tender; for I loved her so utter, as you do know; and I to tell her, as you sure likewise to have told your maid, that I wanted a pocket sufficient, that I might have her therein alway anigh to my heart; and this thing I say to her, as a man that doth love, shall say it; and you to know the way of it so well as I. And she to laugh very mischievous, and to tell me that she should truly tickle me, if that I carried her thatwise; aye and to pinch me, too. And I to have no answer, save that I shake her, very gentle, but indeed she to kiss me very naughty on the mouth, in the midst of my shaking; and truly what shall a man do with such an one.

What indeed?

I had no difficulty locating this passage — I just opened my copy of The Night Land to its second half and picked a page at random, confident that it would contain something suitably risible. Quite apart from my maid’s likely reaction if I told her that I would like to have a pocket to put her in (the House of Silence ain’t got nothin’ on her), there are 200 pages of this. I don’t think Hodgson wanted his readers to wind up pleading for the narrator to brain his Love with a rock and leave her for the reeking giant slugs and gibbering ab-human monstrosities to devour, but that was literally my reaction.

It just doesn’t work. From the midpoint on, the artificiality of the language becomes an enormous liability, as it fuses with the unbelievability of the relationship to make a kind of mutual suicide pact between form and content; it makes the last half of this highly individual and eccentric work come close indeed to being “impenetrable” and “unreadable.”

William Hope Hodgson

Close, I said; I made it, but by the time I crawled over the finish line, I was bruised, bloodied, and bowed, half-drowned under deluges of sugar water and beaten senseless by cruel barrages of flowery verbiage.

But however much you might want to, you can’t just dismiss the book’s second half as an unfortunate misstep or an ill-conceived and dispensable blunder. In fact, it’s impossible to escape the conclusion that all of the “nauseously sticky romantic sentimentality,” all of the intolerably coy kissing and embracing and eyelash-fluttering, all the faith-pledging and selfless sacrifice on Milady’s altar, all of, in short, this LOVE stuff, is what meant the most to its author. Love — and not the uniquely weird and awesome imagery that readers from the beginning have valued so highly — is the heart and soul of the book; it’s why Hodgson wrote it. Mawkish and excessive as his expression of it may seem to us, there can be no doubt that he meant every word of it. As brilliant and memorable as the first half of The Night Land is, I’m certain that what we’re meant to carry away with us is what’s summed up in the book’s final paragraph:

And I to have gained Honour; yet to have learned that Honour be but as the ash of Life, if that you not to have Love. And I to have Love. And to have Love is to have all; for that which doth be truly LOVE doth mother Honour and Faithfulness; and they three to build the House of Joy.

One only wishes that Hodgson had found a better way to convey this, but even with all of his errors of conception and execution, his message does come through, and it can’t help but mean something to us because it clearly meant so much to him. “Sticky” this image of love may be, but like it or not, William Hope Hodgson’s reckless commitment to it finally manages to imbue his ideal with an undeniable weight. If you make it that far.

The Night Land in its unadulterated form is certainly not everyone’s cup of tea. A large number of fantasy readers will likely find Hodgson’s original version unreadable or nearly so, and for that I cannot blame them. Vast tracts of it are a real slog, even if, as I do, you have a taste for very strange stories told in a baroque and convoluted language. The rewards of perseverance are large but so are the costs. Every reader will have to decide for him or herself in which direction the scales tip.

That said, there are books of this difficult sort that having once read, I know that I will one day revisit — books like the Gormenghast Trilogy, A Voyage to Arcturus, The Well at the World’s End, The King of Elfland’s Daughter, and The Worm Ouroboros. This book, though… I’m glad that I read it, and I’m even gladder that I’m finished with it; unlike the books I named earlier, I know that I will pass The Night Land‘s way but once.

In any case, whatever you do, be very careful which Black Gate articles you read, or before you know it you may find yourself stumbling around in the dark, dodging scorpions, choking on sulfur, and muttering, “Ozment… just let me get my hands on Nick Ozment… ”

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was a review of the film Tribulation 99.

I picked up a copy of “The House on the Borderland” in a slim little Ace paperback over 50 years ago, and read it in my teens. Freaky scary. Read it again about 6-7 years ago when I taught a directed-study college student who wanted to do his cornerstone class on Horror fiction. Didn’t like it so much second time around, and to be honest, wondered why I’d enjoyed it so much the first time. I’ve got the 2-volume Ballantine Adult fantasy pb of “The Night Land,” but I also have “The Boats of the ‘Glen Carrig,'” which, oddly enough, I started yesterday and finished today. Told from the first-person viewpoint of a late 18th century traveler, the language was a little stilted and formal, but after 30 or so pages, I got used to it. There were definitely some cringe-inducing elements of the story, and although I floundered a time or two when the pace slowed down, it didn’t take long to get back on track. The last 40 or so pages [POTENTIAL SPOILER ALERT], however, bogged down over a lengthy process dealing with a rescue operation and the introduction of some new characters. Better than “House/Borderland,” but at 176 pages, could’ve benefited from some better pacing.

I read Borderland years ago and Glen Carrig just a year or two ago. They’re both terribly flawed as you say, Smitty, and yet you can’t just dismiss them. I think it’s a disservice to Hodgson to regard him as a novelist at all and hold him to novelistic standards; he was fundamentally a visionary who couldn’t think of any way to convey his visions but put them into these stories. In some ways I think they would have worked better as music or some kind of visual art, if he had had that kind of talent.

It took a couple of tries, but I did eventually get through the entire Night Land when I was doing a full Ballantine Adult Fantasy read-through; and one of these years I’ll read it again, this time in the Night Shade Collected Hodgson. I love the imagery — the names of the places & creatures are impossibly evocative — but the language is almost impenetrable; much less accessible even than William Morris or E.R. Eddison.

(And I was discussing the book with one of the guys at Uncle Hugo’s many years ago, and he suggested that Hodgson wrote the entire, massive tome primarily to justify the scene in the middle where Our Hero and his lady fair actually (gasp!) BATHE TOGETHER! Like, maybe even all nekkid and stuff!

There’s a lot of bathing in the book – in sulfur water, no less! Phewww…

Where did the Nightland map come from? Is that from some RPG?

I’m not sure what the map’s origin is, James. I found it online as I was preparing this article. I wish I’d had it when I was reading the book; it would have made the story a little easier to follow.

What would a Night Land RPG be like? I can’t even imagine…

“What would a Night Land RPG be like? I can’t even imagine.”

I found this to be an interesting read.

http://nightland.website/index.php/background/essays/194-gaming-in-the-night-land

Thomas, you found the prose difficult in King of Elfland?

As far as my own Mount Everest, I’ve been stalled in Well at World’s End for years. This even though I’ve read plenty of other Morris with alacrity—particularly House of the Wolfings!

Gabe, I didn’t find The King of Elfland’s Daughter a particularly difficult read, but I think some would find the “high fantasy” diction a hard pull. I loved the Well – I think it’s a very great book, maybe the greatest of those I mentioned. A Voyage to Arcturus was probably the toughest of the lot.

For me, probably the toughest book to get through (worse than The Night Land, although shorter) was George Meredith’s Shaving of Shagpat, which was just ridiculously florid:

Now, the story of Shibli Bagarag, and of the ball he followed, and of the subterranean kingdom he came to, and of the enchanted palace he entered, and of the sleeping king he shaved, and of the two princesses he released, and of the Afrite held in subjection by the arts of one and

bottled by her, is it not known as ’twere written on the finger-nails of men and traced in their corner-robes?

Oh Lord, Joe, you’re right – I had forgotten about The Shaving of Shagpat! I read it two or three years ago, mostly because Lin Carter really hyped it. Serious drudgery. Hey – we live in an age of mashups…how a about a combination of Night Land and Shagpat?! Waddya think?

Have always like Hodgson since reading Boats of the Glen Carrig, and the Carnacki mysteries. I once produced a reading of his short story, The Hog, for a radio program I did on Saturday Mornings. In spite of the age of this story, which we were reading live over the air, we received a call from a mother complaining that we were scaring her 10 year old son. And this was at 9:30 in the morning! After the show we talked to the lad on the phone for about 20 mins to calm him down. But I was struck by how good a writer Hodgson was to still have such an impact all these decades after his untimely death.

Thomas — the mind boggles and/or shudders at the notion.

I’ve actually read a fair amount of Hodgson at this point — the first three volumes of the Night Shade collected edition, so House on the Borderlands and the Carnacki stuff, and most of the nautical stories. Say what you will about WHH, he really knew his way around a ship. (Mostly because he had actually worked as a sailor, right at the point where sails were giving way to coal.)