Edith Wharton, Jean Cocteau, and an Ancient Mesopotamian Tale

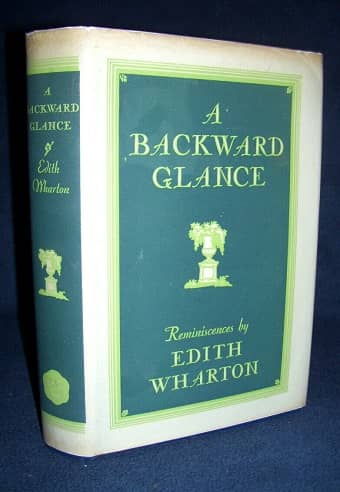

I have been making my way through Edith Wharton’s autobiography, A Backward Glance. Along the way I found an interesting bit about a famous (even notorious) French poet and filmmaker, and especially an ancient story he told her.

I have been making my way through Edith Wharton’s autobiography, A Backward Glance. Along the way I found an interesting bit about a famous (even notorious) French poet and filmmaker, and especially an ancient story he told her.

Wharton describes her time in Paris, particularly pre-World War I. As usual she spends most of her time describing the interesting people she knew there. One of these is Jean Cocteau, and she recounts a tale Cocteau told her, that he claims “he read somewhere.” Here is the story, which many of you will recognize, in a slightly different form:

One day when the Sultan was in his palace at Damascus a beautiful youth who was his favourite rushed into his presence, crying out in great agitation that he must fly at once to Baghdad, and imploring leave to borrow his Majesty’s swiftest horse.

The Sultan asked why he was in such haste to go to Baghdad. ‘Because,’ the youth answered, ‘as I passed through the garden of the Palace just now, Death was standing there, and when he saw me he stretched out his arms as if to threaten me, and I must lose no time in escaping from him.’

The young man was given leave to take the Sultan’s horse and fly; and when he was gone the Sultan went down indignantly into the garden, and found Death still there. ‘How dare you make threatening gestures at my favourite?’ he cried; but Death, astonished, answered: ‘I assure your Majesty I did not threaten him. I only threw up my arms in surprise at seeing him here, because I have a tryst with him tonight in Baghdad.’

Wharton claims never to have been able to trace the story. Curiously, A Backward Glance was published in 1934, almost exactly simultaneously with John O’Hara’s novel Appointment in Samarra. I wonder if Wharton read the novel — or at least its epigraph – in which of course O’Hara gives another version of the story! (Or if she ever saw W. Somerset Maugham’s play, from which O’Hara got his version.)