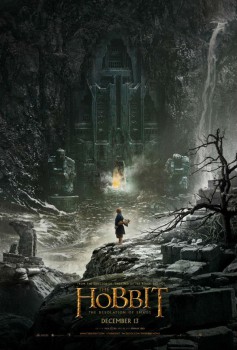

First Full-length Trailer Released for The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug

Curse teaser trailers and their teasing ways! I was teased as a kid, teased all through high school, and now I have to put up with teaser trailers. The universe, it is a cruel place.

Curse teaser trailers and their teasing ways! I was teased as a kid, teased all through high school, and now I have to put up with teaser trailers. The universe, it is a cruel place.

Fortunately, teaser trailers are followed by full-length trailers. Eventually. As has now happened with The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug, the second installment in the three-part Hobbit epic from New Line Cinema and WingNut films. The story picks up where last year’s billion-dollar blockbuster The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey left off, following Bilbo, Gandalf, Thorin and their dwarven companions into the Kingdom of Erebor, the dark heart of Mirkwood and the Necromancer’s lair, Esgaroth, and finally the human town of Dale to confront the dragon Smaug.

The trailer has some nice surprises, including plenty of scenes of Orlando Bloom as Legolas and Lost alum Evangeline Lilly as the elf Tauriel. If you watch closely, you can see the spiders of Mirkwood, the barrel escape down the river, and our first look at the terrifying Smaug himself.

The trilogy will conclude next year with The Hobbit: There and Back Again. All three films are based on J.R.R. Tolkien’s novel The Hobbit, originally published in 1937.

The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug was directed by Peter Jackson and written by Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens, and Peter Jackson. It stars Martin Freeman, Richard Armitage, Ian McKellen, Cate Blanchett, Hugo Weaving, Elijah Wood, Christopher Lee, and A-lister villain Benedict Cumberbatch as both Smaug and The Necromancer Sauron. Check out the complete trailer below.