On Monday, July 31, I had three movies I wanted to see at the Fantasia Festival. First up was a surreal Japanese animated comedy, Night Is Short, Walk On Girl (Yoru wa Mijikashi Arukeyo Otome) in the De Sève Theatre. Then I’d stay at the De Sève to see an Italian documentary, Deliver Us (the English translation of the Latin title Libera Nos), about real-life exorcisms. The day would wrap up in the Hall Auditorium with a screening of Takashi Miike’s adaptation of the best-selling supernatural samurai manga Blade of the Immortal (Mugen no Junin). It looked, all told, like a lovely day.

On Monday, July 31, I had three movies I wanted to see at the Fantasia Festival. First up was a surreal Japanese animated comedy, Night Is Short, Walk On Girl (Yoru wa Mijikashi Arukeyo Otome) in the De Sève Theatre. Then I’d stay at the De Sève to see an Italian documentary, Deliver Us (the English translation of the Latin title Libera Nos), about real-life exorcisms. The day would wrap up in the Hall Auditorium with a screening of Takashi Miike’s adaptation of the best-selling supernatural samurai manga Blade of the Immortal (Mugen no Junin). It looked, all told, like a lovely day.

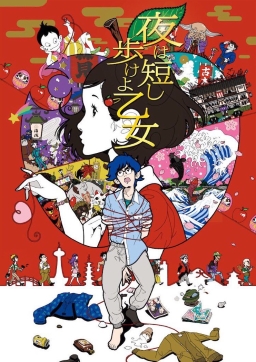

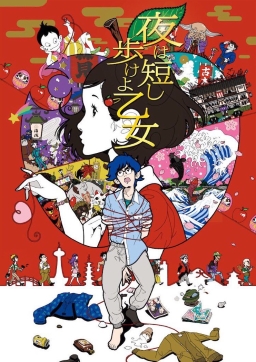

Night Is Short, Walk On Girl was written by Tomohiko Morimi from a novel by Makoto Ueda, and directed by Masaaki Yuasa. Yuasa’s previously overseen an animated TV adaptation of another Ueda novel, Tatami Galaxy; the stories share a setting and some minor characters, but there’s nothing obtrusive to someone like me who has neither seen nor read Tatami Galaxy. Walk On Girl takes place in Kyoto, following a group of university students through a long night of seeking love, of seeking a long-lost and beloved book, and of encountering supernatural and near-supernatural entities. It mainly centres on a male student, called only Senpai (‘senior,’ voiced by Gen Hoshino), who is in love with a girl called Kurokami no Otami (literally, ‘the girl with black hair,’ here played by Kana Hanazawa). Senpai’s been arranging seemingly-accidental meetings, hoping Otami will notice him; on the night the film follows them, she goes partying and ends up looking for a copy of a beloved storybook from her childhood. This swiftly leads into a proliferation of subplots and genuinely zany characters — from the God of the Old Books Market (Hiroyuki Yoshino), to the School Festival Executive Head (Hiroshi Kamiya) who keeps the University campus under constant surveillance, to ‘Don Underwear’ (Ryuji Akiyama) who will not change his drawers until he finds (through the medium of pop-up theatrical happenings) the girl he once saw and fell in love with. The film whirls along through the night in a delirious whirl of pub crawling, dancing, philosophers (dancing and otherwise), guerilla theater, used book fairs, surveillance, cross-dressing, wishes, bad colds, punching technique, clocks, night, and true love.

I was worried for most of the film that Senpai’s obsession with Otami, which at least borders on stalking, would be glossed over. In fact it is at least addressed toward the end of the film, and the constant humiliations Senpai brings on himself throughout the movie certainly can be seen as a kind of poetic justice for his actions. In this as in much else the film is aware of its dark undertones, but maintains a generosity of spirit despite them. It’s a movie that maybe more than any other I’ve seen captures the university experience — or what one might hope the university experience would be like. It does this without naivete; it is clearly the product of older creators telling a tale of youth, but doing it without either speaking down to the young in any way or, conversely, romanticising the experience of youth.

…

Read More Read More

With another year’s worth of Fantasia reviews now finished, I thought I’d take the time once again to look back at what I saw and write a general overview of the films as a whole. Doing so this year, though, leads to thoughts about film on a slightly larger scale than just Fantasia alone.

With another year’s worth of Fantasia reviews now finished, I thought I’d take the time once again to look back at what I saw and write a general overview of the films as a whole. Doing so this year, though, leads to thoughts about film on a slightly larger scale than just Fantasia alone. After the Fantasia festival had officially concluded I still had three movies to watch. During the festival I’d requested links to view screening copies of three films I couldn’t see in theatres due to schedule conflicts, but it wasn’t until Fantasia ended that I had time to sit down and watch them. These movies were a Japanese comedy-drama called Japanese Girls Never Die (also released under the English title Haruko Azumi Is Missing, in romanised Japanese Azumi Haruko wa yukue fumei); a Thai historical martial-arts movie called Broken Sword Hero (also Legend of the Broken Sword Hero, from the romanised original Thong Dee Fun Khao); and a Chinese blockbuster historical war movie called God of War (Dang kou feng yun, now on Netflix). They made for an interesting mix.

After the Fantasia festival had officially concluded I still had three movies to watch. During the festival I’d requested links to view screening copies of three films I couldn’t see in theatres due to schedule conflicts, but it wasn’t until Fantasia ended that I had time to sit down and watch them. These movies were a Japanese comedy-drama called Japanese Girls Never Die (also released under the English title Haruko Azumi Is Missing, in romanised Japanese Azumi Haruko wa yukue fumei); a Thai historical martial-arts movie called Broken Sword Hero (also Legend of the Broken Sword Hero, from the romanised original Thong Dee Fun Khao); and a Chinese blockbuster historical war movie called God of War (Dang kou feng yun, now on Netflix). They made for an interesting mix. On the last day of the 2017 Fantasia film festival I planned to watch three movies. First, at the De Sève Theatre, Indiana: a movie about a pair of ghost-breakers in the Midwest who may or may not deal with actual paranormal events. Second, I’d go to the festival’s screening room, where I’d see a dark psychological thriller called Fashionista. Finally, I’d close out the festival with a screening of a restored version of Dario Argento’s classic 1977 horror film Suspiria.

On the last day of the 2017 Fantasia film festival I planned to watch three movies. First, at the De Sève Theatre, Indiana: a movie about a pair of ghost-breakers in the Midwest who may or may not deal with actual paranormal events. Second, I’d go to the festival’s screening room, where I’d see a dark psychological thriller called Fashionista. Finally, I’d close out the festival with a screening of a restored version of Dario Argento’s classic 1977 horror film Suspiria. Tuesday, August 1, was the next-to-last day of Fantasia. I had three films I wanted to see as the festival raced to its end, all at the De Sève Theatre. Lu Over the Wall (Yoake Tsugeru Lu no uta) was an animated young person’s adventure about indie rock and mermaids, from the mind of Masaaki Yuasa. Spoor (Pokot) was a Polish-Czech co-production of a mystery-horror film about animals that may or may not be turning against human beings. And Nomad (Göçebe) was a Turkish science-fiction/fantasy film that promised mythic overtones.

Tuesday, August 1, was the next-to-last day of Fantasia. I had three films I wanted to see as the festival raced to its end, all at the De Sève Theatre. Lu Over the Wall (Yoake Tsugeru Lu no uta) was an animated young person’s adventure about indie rock and mermaids, from the mind of Masaaki Yuasa. Spoor (Pokot) was a Polish-Czech co-production of a mystery-horror film about animals that may or may not be turning against human beings. And Nomad (Göçebe) was a Turkish science-fiction/fantasy film that promised mythic overtones.

On Monday, July 31, I had three movies I wanted to see at the Fantasia Festival. First up was a surreal Japanese animated comedy, Night Is Short, Walk On Girl (Yoru wa Mijikashi Arukeyo Otome) in the De Sève Theatre. Then I’d stay at the De Sève to see an Italian documentary, Deliver Us (the English translation of the Latin title Libera Nos), about real-life exorcisms. The day would wrap up in the Hall Auditorium with a screening of Takashi Miike’s adaptation of the best-selling supernatural samurai manga Blade of the Immortal (Mugen no Junin). It looked, all told, like a lovely day.

On Monday, July 31, I had three movies I wanted to see at the Fantasia Festival. First up was a surreal Japanese animated comedy, Night Is Short, Walk On Girl (Yoru wa Mijikashi Arukeyo Otome) in the De Sève Theatre. Then I’d stay at the De Sève to see an Italian documentary, Deliver Us (the English translation of the Latin title Libera Nos), about real-life exorcisms. The day would wrap up in the Hall Auditorium with a screening of Takashi Miike’s adaptation of the best-selling supernatural samurai manga Blade of the Immortal (Mugen no Junin). It looked, all told, like a lovely day. I ran up the steps in the Hall Building, hurrying from the basement where I’d just seen

I ran up the steps in the Hall Building, hurrying from the basement where I’d just seen