Fantasia 2017, Day 15: Solving Mysteries, Or Not (Town In A Lake and Let There Be Light)

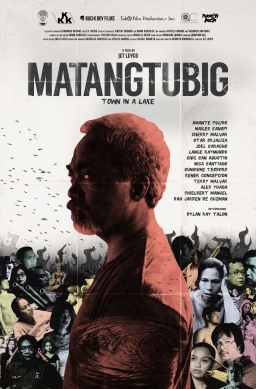

On Thursday, July 27, I planned to watch two films at the Fantasia International Film Festival. First, an artistically ambitious movie from the Philippines called Town In A Lake (Matangtubig). Then, later in the evening, a documentary about the quest to develop nuclear fusion technology called Let There Be Light. Both looked to be about the mysteries of the universe, in very different ways.

On Thursday, July 27, I planned to watch two films at the Fantasia International Film Festival. First, an artistically ambitious movie from the Philippines called Town In A Lake (Matangtubig). Then, later in the evening, a documentary about the quest to develop nuclear fusion technology called Let There Be Light. Both looked to be about the mysteries of the universe, in very different ways.

Directed by Jet Leyco and written by Brian Gonzales, Town In A Lake takes place in a small isolated town in the Philippine jungle with an official crime rate of zero. Until, as the movie opens, two girls are abducted. One is later found dead. The crime draws the attention of the national and international media, which descends on the town, disrupting the locals’ lives and mourning. Meanwhile, the investigation into the crime goes on. Who committed this evil, and why? Can there be a wholly natural explanation for it, coming on the heels of so much peace?

Watching Town In A Lake is only part of the experience of the film. It’s a story that doesn’t provide easy explanations, or even that much in the way of conventional character-centred drama. There are characters, and there is what is effectively a mystery story that ultimately takes on aspects beyond the merely rational. But these things emerge over the course of the film’s 88 minutes; we assemble the bits we’re given, the sounds and images we experience, and make the pieces make sense even as we’re absorbed by the sensory depth of the movie. This is a meditative experience, with long takes and subtle camera moves and a rich soundscape. Still, I found it took some pondering to understand (and I want here to express my thanks to filmmakers Shelagh Rowan-Legg and Gabriela MacLeod as well as critic Kurt Halfyard for a useful discussion after the film that clarified many things for me). There is a good argument that in attempting to understand what we see rationally, in attempting to work it out like a logic puzzle, one does not take the best approach to the film — that in so doing we come like the outsider media, imposing our own frames of understanding on matter that is richer and more allusive than can be explained by words and reason. “Relax,” runs one line of dialogue, “thinking won’t get you anywhere.” On the other hand, there is a counter-argument that if this is so, any explanation will be self-evidently insufficient, that the emotional and sensory resonance will naturally and necessarily dwarf the meaning of the logic. So it is here, I think. You can work out a perfectly sound explanation of what’s happening onscreen. But there is always more than the explanation can resolve. There are always more mysteries.

What are the mysteries about? What is the nature of the experience we’re meant to have? To me, there’s a documentary feel to the film, which nevertheless mixes the realistic and the sublime — the beauty of the natural world, and what appears to be supernatural. In this way it’s like the Estonian November. The supernatural isn’t distinct from the tactile, the sensory, the everyday. It’s part of what shapes things. Mysterious things happen in this film — the opening crime, a later disappearance — and it’s a part of life. Because life itself is mysterious and supernatural, as much as it is filled with toil and crime and authority. There’s an almost overwhelming visual sense of the jungle, of the denseness of it, of the way it surrounds the town on one side much as the water does on the other; it is both nature and the womb of the supernatural, the source of a meaning that is other than the purely human. I think that’s relevant to the themes of the film, which I read as being about harmony and the price one pays for harmony. About the conflict of tradition and modernity, surely, but also the prices paid by either lifestyle. It is about the ways one lives with the unexpected and dangerous and tragic, perhaps.

What are the mysteries about? What is the nature of the experience we’re meant to have? To me, there’s a documentary feel to the film, which nevertheless mixes the realistic and the sublime — the beauty of the natural world, and what appears to be supernatural. In this way it’s like the Estonian November. The supernatural isn’t distinct from the tactile, the sensory, the everyday. It’s part of what shapes things. Mysterious things happen in this film — the opening crime, a later disappearance — and it’s a part of life. Because life itself is mysterious and supernatural, as much as it is filled with toil and crime and authority. There’s an almost overwhelming visual sense of the jungle, of the denseness of it, of the way it surrounds the town on one side much as the water does on the other; it is both nature and the womb of the supernatural, the source of a meaning that is other than the purely human. I think that’s relevant to the themes of the film, which I read as being about harmony and the price one pays for harmony. About the conflict of tradition and modernity, surely, but also the prices paid by either lifestyle. It is about the ways one lives with the unexpected and dangerous and tragic, perhaps.

Which sounds abstract, but the movie really isn’t. It’s difficult to talk about character here because it tends to work almost through a series of vignettes, showing the police trying to solve the crime (or are they?), politicians trying to exploit the situation for votes, media personalities chatting about the tragedy trending on social media as they deform the village life simply by going about their business. There’s a humanistic sense here, to be sure, and yet also an oddly detached viewpoint. If one were bound and determined to fit this movie into a genre box, it’d probably be closest to horror, not only in the overall tone and final explanation of events, but in the way that common life comes to feel like an evasion of a deeper and more threatening reality. It’s possible that the town in a lake has a connection to more profound powers than the outsiders understand. But is that necessarily a good thing?

Which sounds abstract, but the movie really isn’t. It’s difficult to talk about character here because it tends to work almost through a series of vignettes, showing the police trying to solve the crime (or are they?), politicians trying to exploit the situation for votes, media personalities chatting about the tragedy trending on social media as they deform the village life simply by going about their business. There’s a humanistic sense here, to be sure, and yet also an oddly detached viewpoint. If one were bound and determined to fit this movie into a genre box, it’d probably be closest to horror, not only in the overall tone and final explanation of events, but in the way that common life comes to feel like an evasion of a deeper and more threatening reality. It’s possible that the town in a lake has a connection to more profound powers than the outsiders understand. But is that necessarily a good thing?

None of this would work if the town itself didn’t feel like a real place. Which it does, not just because of the sense of place created by sound and image, but because the community feels real. The characters interact believably, and by the end of the film one comes to understand (perhaps) what it is that drives each of them, why they do what they do as the crime’s investigated. What threats are involved. The ambiguous nature of authority, and how thin the local authority’s commitment to human rights may be. Because the sense of the town’s so strong, the feeling of invasion by the outside world is equally strong. We can understand these media people, and also understand how out-of-place they are. They’ve got a job to do. But they do it without care for what they’re disturbing in the process, like scientists measuring details so fine the mere act of observation changes what is being observed.

One might argue that the act of observation is crucial to this film; it is nominally a mystery story, after all, with clues and witnesses key to the tale. But then it also seems to question or challenge the act of seeing. One of its more notorious scenes is an autopsy in which the genitals of a dead girl are centred in the frame, so that we as the audience are confronted with an uncomfortable image in one of the film’s many long takes. It is easily possible to argue both the validity of the artistic choice and the validity of a reaction that takes a viewer out of the film. The sense of a documentary, here as elsewhere, paradoxically reminds us that reality has much that we do not always need to see to understand. Still, the fragments we get serve in the end to build up to a surprisingly apocalyptic climax. Without wanting to give too much away, my understanding of the film’s story is oddly close to Le Guin’s parable “Those Who Walk Away From Omelas”: What is the price of paradise? Appropriately, there are no answers here. Only one possible outcome to one set of events. Town In A Lake is a powerful meditation in itself, and a cause of meditation in others.

One might argue that the act of observation is crucial to this film; it is nominally a mystery story, after all, with clues and witnesses key to the tale. But then it also seems to question or challenge the act of seeing. One of its more notorious scenes is an autopsy in which the genitals of a dead girl are centred in the frame, so that we as the audience are confronted with an uncomfortable image in one of the film’s many long takes. It is easily possible to argue both the validity of the artistic choice and the validity of a reaction that takes a viewer out of the film. The sense of a documentary, here as elsewhere, paradoxically reminds us that reality has much that we do not always need to see to understand. Still, the fragments we get serve in the end to build up to a surprisingly apocalyptic climax. Without wanting to give too much away, my understanding of the film’s story is oddly close to Le Guin’s parable “Those Who Walk Away From Omelas”: What is the price of paradise? Appropriately, there are no answers here. Only one possible outcome to one set of events. Town In A Lake is a powerful meditation in itself, and a cause of meditation in others.

I saw Town In A Lake in the small De Sève theatre; after a dinner and discussion I went to the basement of the Hall Building to see a movie in the nearly 400-seat D.B. Clarke Theatre. This was the documentary Let There Be Light, which was preceded by a short horror film called “Late Tales.”

I saw Town In A Lake in the small De Sève theatre; after a dinner and discussion I went to the basement of the Hall Building to see a movie in the nearly 400-seat D.B. Clarke Theatre. This was the documentary Let There Be Light, which was preceded by a short horror film called “Late Tales.”

Written and adapted by Gauthier Aboudaram, “Late Tales” is a set of four anecdotes based on creepypasta, often-anonymous brief horror stories that circulate on the internet. There’s no plot connection between these four short tales, but there’s a thematic similarity of strange and frightening things happening to (middle-class North American) families. The stories are shot similarly, in a muted, straightforward way that brings out the eerieness of the anecdotes. Together the four pieces total 8 minutes, so they certainly don’t overstay their welcome, and indeed make their points with an admirable brevity. Of the four — “Dreams,” “Lullaby,” “Darling,” and “Sleepwalk” — I found I preferred the middle two, which struck me as a little more subtler than the others, getting gooseflesh to rise out of simpler means. But all four segments are effective, and together make for a strong short film.

Let There Be Light, directed by Mila Aung-Thwin and cinematographer Van Royko, is a clever and informative documentary that finds idealism and an emotional core in the quest to make nuclear fusion an economically viable way to generate electric power. It loosely focuses on three scientists, engaged in three different projects to create working fusion reactors. The first, with whom we spend the most time, is Mark Henderson of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Project (the acronym for which is, not coincidentally, Latin for “the way”); ITER is a massive, complex, and costly project to build a huge nuclear fusion reactor called a tokamak in France. Contrasting with ITER, funded publically by several different governments, are Michel Laberge of the private Canadian start-up General Fusion and Eric Lerner whose company LPPFusion is trying to create a compact nuclear fusion reactor in a storage facility in New Jersey. Interwoven among them are animated segments explaining the history and concepts of fusion, and why this technique, if perfected, could revolutionise human society by providing virtually unlimited clean energy.

The three scientists are the heart of the film, along with the administrators and others at ITER trying to make fusion power a reality. There’s an incredible dedication common to all the people in this movie, all of them possessed of a strong and infectious sense of mission. They know how important fusion power can be, and how damaging carbon-fuelled energy is to the health of the planet. They all see the same way out: make an artificial sun in a bottle, and use it to power humanity. They have different approaches, but that dream drives them all, giving the movie an unusual immediacy and sense of importance.

The three scientists are the heart of the film, along with the administrators and others at ITER trying to make fusion power a reality. There’s an incredible dedication common to all the people in this movie, all of them possessed of a strong and infectious sense of mission. They know how important fusion power can be, and how damaging carbon-fuelled energy is to the health of the planet. They all see the same way out: make an artificial sun in a bottle, and use it to power humanity. They have different approaches, but that dream drives them all, giving the movie an unusual immediacy and sense of importance.

“Unusual” because fusion’s not going to be a reality in the short term. ITER, the surest bet to create a working fusion reactor, will take decades to come online. If it does, if it’s funded and built, it will be the single most complex thing ever planned and built by human beings, with a million separate pieces working to create an incredibly advanced and precise technology. But it won’t be able to provide enough power for the entire world on its own. Hence the necessity for the projects of Laberge and Lerner (as well as other projects aiming at compact fusion not shown in the movie, such as Lockheed Martin’s). Lerner in particular is critical of the way in which ITER draws the vast majority of the funding for fusion power, while alternate theories such as his own get shorter shrift.

Similarly, ITER seems to take up the majority of the film. It’s a troubled project in some ways, as the history of fusion has been troubled. Fusion’s been dogged in the past by claims that were either deliberately fraudulent or simply wrong; a belief in the late 20th century that workable fusion was just around the corner turned out to be sadly unfounded, and with few results to point to, it’s difficult now to get the amount of funding needed to keep the project advancing. Henderson compares his work to that of a man building a medieval cathedral — a great and complex work at the bleeding edge of technology, and one that may take longer than his lifespan to complete.

But ITER itself has had some management issues. People are reluctant to say anything bad about the project on film (though footage of the occasional press conference reveals a more sceptical media). Still, it seems clear that management in the past has not been effective at handling the various logistical issues involved in such a complex project, which has cost (so far) billions of dollars and involved the co-ordination of multiple governments, as well as suppliers from around the world. The documentary’s effective at bringing all these difficulties out, at the same time as we see a new Director-General, Bernard Bigot, take over and seem to get the project on a sounder footing.

Bigot shares a favourite quote with the filmmakers: “Where there is no vision, the people perish” (Proverbs 29:18). It fits with the overall feel of mission in the film. An American coordinator reflects that the ITER project is more complex than the International Space Station, which he was also involved with, and says: “This is a real test of human civilisation, and it’s a test we can’t afford to fail. We have to prove that we have the intelligence to prevent our own extinction.” If the science of fusion may be esoteric to many people, the importance becomes clear, and the success of the film is that it brings home the importance of the fusion projects to the world at large.

Bigot shares a favourite quote with the filmmakers: “Where there is no vision, the people perish” (Proverbs 29:18). It fits with the overall feel of mission in the film. An American coordinator reflects that the ITER project is more complex than the International Space Station, which he was also involved with, and says: “This is a real test of human civilisation, and it’s a test we can’t afford to fail. We have to prove that we have the intelligence to prevent our own extinction.” If the science of fusion may be esoteric to many people, the importance becomes clear, and the success of the film is that it brings home the importance of the fusion projects to the world at large.

Some of that comes through skillful editing equally effective at selecting human moments and at presenting information quickly and clearly. Some of that comes through the use of devices such as the stylish animated sequences. But much of that comes through the human relatability of the scientists who carry the movie. Henderson has the most powerful set-piece of the film, as we see him on the ITER construction site, passionately trying to get across to some construction workers the importance of the fusion project, and the dream the construction will make real.

ITER is a greater technical challenge than the moon walk or sequencing DNA. Let There Be Light, with its appropriately Biblical title, taps into the grandeur of the scheme. This is almost literally the creation of a small artificial sun in a sealed space. The trick is to make sure more power is produced by the sun than is taken up in creating it. And yet the drama doesn’t come from competition among scientists, who mostly seem to respect each other and the different approaches to fusion. The drama comes from the political aspects of the project, not just directly from the expense of building ITER but the broader implications of finding a clean means of generating energy. This in a world where a political faction in one specific country is trying to deny the reality of carbon fuels’ effect on the environment. This is a story of science, of idealism, and of the way in which science must be done. The way it must operate within a political context, even while, paradoxically, it aims at long-term goals alien to the time-scales on which politics operates. It’s a powerful film, engaging if unyielding, and ultimately inspiring.

ITER is a greater technical challenge than the moon walk or sequencing DNA. Let There Be Light, with its appropriately Biblical title, taps into the grandeur of the scheme. This is almost literally the creation of a small artificial sun in a sealed space. The trick is to make sure more power is produced by the sun than is taken up in creating it. And yet the drama doesn’t come from competition among scientists, who mostly seem to respect each other and the different approaches to fusion. The drama comes from the political aspects of the project, not just directly from the expense of building ITER but the broader implications of finding a clean means of generating energy. This in a world where a political faction in one specific country is trying to deny the reality of carbon fuels’ effect on the environment. This is a story of science, of idealism, and of the way in which science must be done. The way it must operate within a political context, even while, paradoxically, it aims at long-term goals alien to the time-scales on which politics operates. It’s a powerful film, engaging if unyielding, and ultimately inspiring.

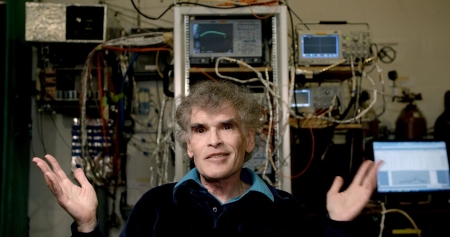

After the movie, there was an extensive question-and-answer period with directors Mila Aung-Thwin and Van Royko, as well as special guest Mark Henderson. It’s a mark of the success of the film, perhaps, that the audience seemed especially appreciative of Henderson’s presence and directed most of their questions to him (as always, what follows is drawn from handwritten notes, and please bear in mind here I’m a former English student writing about physics). First, though, the directors were asked how the film came to be, and how they knew they had a story to tell about renewable energy. Aung-Thwin said he always knew he wanted to do something about energy, and it happened at one point in trying to develop something around that idea that the directors got a free trip to ITER. There, he saw a boring powerpoint presentation — and at the end, Henderson got up and talked about his dream, much as he spoke about his dream at the end of the film. That drew the filmmakers in, and gave them the core of the film.

Henderson was then asked how it felt to be involved in a film. He said it was very strange: “I’m a geek scientist.” He said that he felt like he was on stage as a representative of thousands of scientists working on fusion, and that he felt privileged to work with the filmmakers and learn about the process of communicating in their medium. Van Royko observed that Henderson had also once had a dream of being a science teacher, and said he thought Henderson liked the project because it was like being a teacher; Henderson agreed with that.

Henderson was then asked how it felt to be involved in a film. He said it was very strange: “I’m a geek scientist.” He said that he felt like he was on stage as a representative of thousands of scientists working on fusion, and that he felt privileged to work with the filmmakers and learn about the process of communicating in their medium. Van Royko observed that Henderson had also once had a dream of being a science teacher, and said he thought Henderson liked the project because it was like being a teacher; Henderson agreed with that.

Asked if he was optimistic about fusion, Aung-Thwin said he was; he observed he didn’t want to work for years on a dark film. He said it was inspiring to see the idealism and optimism of the scientists working on fusion, and the willingness of the ITER scientists to work on a project that won’t pay off for potentially centuries. Another audience member asked if the international collaboration involved in working on fusion could potentially reduce geopolitical tension; Henderson said that had been his experience working on his master’s thesis in the 1980s, which had involved comparing research in the US and USSR. Fusion research, done in the open, aimed at the betterment of humankind in general.

A question about the funding of ITER led Henderson to observe that Canada, which had once been involved, was no longer a part of the project (which the Canadian Aung-Thwin characterised as an “embarrassment”), and to discuss American funding levels, which the Trump administration was proposing to cut back even further from levels that were already too low. Another audience member asked about the rarity of materials in the ITER tokamak, and Henderson discussed some of the details of the deuterium and lithium fuel as well as the exotic materials used in the machine’s magnets. Asked what the ITER scientists thought of other models and approaches to fusion, Henderson observed it was a dangerous question, and recalled being teased when cold fusion announcements were made; he said in the end he’d be happy if anyone cracked fusion. He personally believes that the tokamak is the most viable solution, but agreed with a statement Eric Lerner of Focus Fusion made that all approaches should be funded in the hopes that one will pay off.

A question about the funding of ITER led Henderson to observe that Canada, which had once been involved, was no longer a part of the project (which the Canadian Aung-Thwin characterised as an “embarrassment”), and to discuss American funding levels, which the Trump administration was proposing to cut back even further from levels that were already too low. Another audience member asked about the rarity of materials in the ITER tokamak, and Henderson discussed some of the details of the deuterium and lithium fuel as well as the exotic materials used in the machine’s magnets. Asked what the ITER scientists thought of other models and approaches to fusion, Henderson observed it was a dangerous question, and recalled being teased when cold fusion announcements were made; he said in the end he’d be happy if anyone cracked fusion. He personally believes that the tokamak is the most viable solution, but agreed with a statement Eric Lerner of Focus Fusion made that all approaches should be funded in the hopes that one will pay off.

Asked about the international response to the movie, Aung-Thwin said it was positive, and noted that in the United States audiences always wanted to know which congressman to call. Audiences everywhere want fusion to work. Another audience member asked who the enemies of fusion development were, and if anyone was actively working against it. Henderson said that in a weird way, everyone in the room is an enemy of fusion; one has to think three or four or five generations along in developing the technology, while humans naturally tend to worry about today. Politicians tend to worry about re-election, and don’t want to invest in an industry that will only provide returns in fifty or sixty years at the earliest. He knows, therefore, that it’s important to change mentalities for fusion to succeed.

Asked why he felt fusion was superior to other renewable energy sources, Henderson clarified that he supports solar and wind and geothermal energy as well; he doesn’t want competition. The virtue of fusion, as he sees it, is that it’s not limited by the hours of sunlight or amount of wind. Van Royko observed that energy isn’t just for the needs of right now, but that there’s a correlation between human advancement and the amount of energy used by humans. Asked about the challenges of rallying public support, Henderson observed that some organisations (such as Greenpeace) look at fusion as simply “nuclear” and oppose it as such (though Henderson observed that he himself preferred fission to carbon fuels). He encouraged everyone to speak up to their government, observing that Justin Trudeau seems more open to supporting fusion. He said he feels that the filmmakers are more important here than his own work, in terms of their ability to educate and spread information.

A question came about the effects that various hoaxes had on the reception of fusion over the years. Henderson observed that cold fusion, for example, wasn’t a “hoax” in that there was a reaction. It doesn’t seem to be efficient enough to be usable as an energy source, though. Henderson said there was a history of optimism in the fusion field, which used to always expect fusion to be workable in ten to twenty years. When that didn’t happen, funding dried up. As late as 1980, it was thought that fusion power would be on the grid in fifty years; now Henderson doesn’t see that happening even fifty years from now. Asked how many tokamaks would be needed to supply the world with energy, Henderson said “a lot.” More than a thousand, he estimated. He observed that China’s building one coal plant per week, so it will take a while to build enough fusion generators to produce that kind of power. Aung-Thwin said that Michel Laberge of General Fusion was hoping to build a machine that could power a small city — and, he went on, imagine how many small cities there are worldwide.

A question came about the effects that various hoaxes had on the reception of fusion over the years. Henderson observed that cold fusion, for example, wasn’t a “hoax” in that there was a reaction. It doesn’t seem to be efficient enough to be usable as an energy source, though. Henderson said there was a history of optimism in the fusion field, which used to always expect fusion to be workable in ten to twenty years. When that didn’t happen, funding dried up. As late as 1980, it was thought that fusion power would be on the grid in fifty years; now Henderson doesn’t see that happening even fifty years from now. Asked how many tokamaks would be needed to supply the world with energy, Henderson said “a lot.” More than a thousand, he estimated. He observed that China’s building one coal plant per week, so it will take a while to build enough fusion generators to produce that kind of power. Aung-Thwin said that Michel Laberge of General Fusion was hoping to build a machine that could power a small city — and, he went on, imagine how many small cities there are worldwide.

That ended the questions on a sobering note. Still, it had been an exhilarating day. If there’s something inherently dreamlike about the cinema, the two films I’d seen were different but equally profound explorations of the nature of dreams. Both were moving, though both spoke to different parts of the viewer, and both rewarded careful watching. It had been a rewarding and educational day; and I had another two films to watch the day after.

(See all my 2017 Fantasia reviews here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.