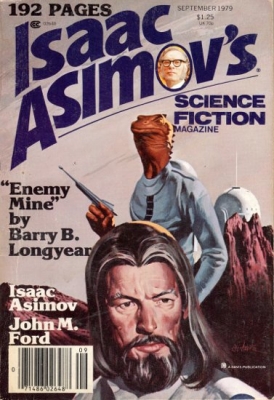

The Golden Age of Science Fiction: “Enemy Mine,” by Barry B. Longyear

The Best Novella category was not one of the original Hugo categories in 1953. I twas introduced in 1968, when it was won by Philip José Farmer for “Riders of the Purple Wage” and Anne McCaffrey for “Weyr Search.” Since then, some version of the award has been a constant, with the exception of 1958. In 1980, the awards were presented at Noreascon II in Boston.

The Nebula Award was created by the Science Fiction Writers of America (SFWA) and first presented in 1966, when the award for Best Novella was won by Brian W. Aldiss for “The Saliva Tree” and Roger Zelazny for “He Who Shapes.” The award has been given annually since then.

The Locus Awards were established in 1972 and presented by Locus Magazine based on a poll of its readers. In more recent years, the poll has been opened up to on-line readers, although subscribers’ votes have been given extra weight. At various times the award has been presented at Westercon and, more recently, at a weekend sponsored by Locus at the Science Fiction Museum (now MoPop) in Seattle. The Best Book Novella Award dates back to 1974, when the short fiction awards were split into Short Fiction and Novella lengths. Frederick Pohl won the first award. In 1980. The Locus Poll received 854 responses.

In January, I wrote about Barry B. Longyear, the winner of the John W. Campbell Award in 1980 and explored the vast amount of fiction he published in 1978 and 1979. At that time, I dismissed his biggest hit with a single line, “His breakout story, of course, was “Enemy Mine,” which will be covered in more depth in the article on that novella’s various awards for the year.” Now is come the time to discuss that story.

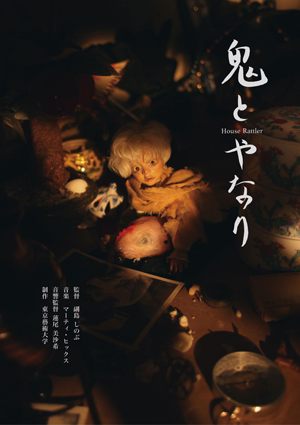

My last screening of July 21 brought me back to the De Sève Theatre for a showcase of animated short genre films from China, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan, a grouping titled “Things That Go Bump In the East.” 11 films in a range of visual styles promised variety. I’d been having good luck with short films at the festival so far, and settled in eager to see what would come now.

My last screening of July 21 brought me back to the De Sève Theatre for a showcase of animated short genre films from China, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan, a grouping titled “Things That Go Bump In the East.” 11 films in a range of visual styles promised variety. I’d been having good luck with short films at the festival so far, and settled in eager to see what would come now. For my third movie of July 21 I wandered back to the Fantasia screening room. There, I settled in with a movie from the Philippines: Ode To Nothing. Written and directed by Dwein Ruedas Baltazar, it follows Sonya (Marietta Subong), a woman no longer young who owns her own funeral home in an unnamed town. Alone except for her father, Rudy (Joonee Gamboa), Sonya tries to keep the funeral home going despite debts to local loan shark Theodore (Dido Dela Paz). Then a body is brought to her for burial under suspicious circumstances. Rather than bury the corpse, though, Sonya begins to speak to it, and comes to think that the body of the old woman is bringing her luck — even to treat the body as her surrogate mother. Is the corpse responsible for the sudden influx of business to the funeral home? And even if it is, can you trust the gifts of the dead?

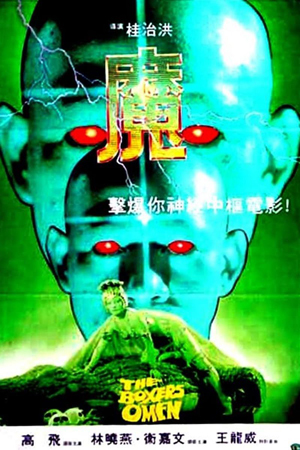

For my third movie of July 21 I wandered back to the Fantasia screening room. There, I settled in with a movie from the Philippines: Ode To Nothing. Written and directed by Dwein Ruedas Baltazar, it follows Sonya (Marietta Subong), a woman no longer young who owns her own funeral home in an unnamed town. Alone except for her father, Rudy (Joonee Gamboa), Sonya tries to keep the funeral home going despite debts to local loan shark Theodore (Dido Dela Paz). Then a body is brought to her for burial under suspicious circumstances. Rather than bury the corpse, though, Sonya begins to speak to it, and comes to think that the body of the old woman is bringing her luck — even to treat the body as her surrogate mother. Is the corpse responsible for the sudden influx of business to the funeral home? And even if it is, can you trust the gifts of the dead? For my second film of July 21 I stayed at the De Sève Theatre to watch one of my more anticipated movies of the festival. Each year Fantasia plays a Shaw Brothers film on 35mm — not one of the Shaw classics, usually, but one of their stranger works. The past few years I’ve seen

For my second film of July 21 I stayed at the De Sève Theatre to watch one of my more anticipated movies of the festival. Each year Fantasia plays a Shaw Brothers film on 35mm — not one of the Shaw classics, usually, but one of their stranger works. The past few years I’ve seen  My first film at Fantasia on July 21 was actually two films put together. In 2009 Atsuya Uki released a 25-minute short he’d written and directed, called “Cencoroll,” based on a one-shot manga he’d written and illustrated. The short was well-received, and over the last decade he’s created a 50-minute follow-up. The two movies have now been released as one, Cencoroll Connect (Senkorōru, センコロール コネクト). They work together as one story, but I wonder, never having seen the original “Cencoroll” on its own, whether the first short would have left more room for an audience’s imagination to work.

My first film at Fantasia on July 21 was actually two films put together. In 2009 Atsuya Uki released a 25-minute short he’d written and directed, called “Cencoroll,” based on a one-shot manga he’d written and illustrated. The short was well-received, and over the last decade he’s created a 50-minute follow-up. The two movies have now been released as one, Cencoroll Connect (Senkorōru, センコロール コネクト). They work together as one story, but I wonder, never having seen the original “Cencoroll” on its own, whether the first short would have left more room for an audience’s imagination to work. My last movie of July 20 was a horror film from South Africa. Written and directed by Harold Holscher, 8 has elements of the classical ghost story embedded in a larger tale of folklore and tragedy. It’s a period tale, set in 1977, and is set in a farm named Hemel op Aarde: Heaven on Earth.

My last movie of July 20 was a horror film from South Africa. Written and directed by Harold Holscher, 8 has elements of the classical ghost story embedded in a larger tale of folklore and tragedy. It’s a period tale, set in 1977, and is set in a farm named Hemel op Aarde: Heaven on Earth. The evening of July 20 saw me stay at the De Sève Theatre after the Born of Woman showcase for a feature film written and directed by Jon Mikel Caballero: The Incredible Shrinking Wknd. It’s a time-loop story, a subgenre that strikes me as having increased in popularity significantly over the past few years. We’re at the point, then, that a time-loop story has to do something different to stand out. So what does Wknd do?

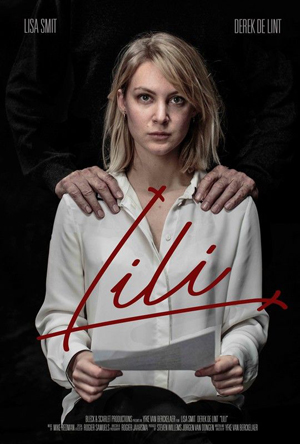

The evening of July 20 saw me stay at the De Sève Theatre after the Born of Woman showcase for a feature film written and directed by Jon Mikel Caballero: The Incredible Shrinking Wknd. It’s a time-loop story, a subgenre that strikes me as having increased in popularity significantly over the past few years. We’re at the point, then, that a time-loop story has to do something different to stand out. So what does Wknd do? On the afternoon of Saturday, July 20, I passed by the De Sève Theatre for the Born of Woman 2019 series of short genre films directed by women. It was the fourth iteration of the showcase, and in four years it’s become a hot ticket; I nearly didn’t get in. But there was just space enough in the end, and so I was able to see the collection of 9 films representing half-a-dozen countries.

On the afternoon of Saturday, July 20, I passed by the De Sève Theatre for the Born of Woman 2019 series of short genre films directed by women. It was the fourth iteration of the showcase, and in four years it’s become a hot ticket; I nearly didn’t get in. But there was just space enough in the end, and so I was able to see the collection of 9 films representing half-a-dozen countries. On Saturday, July 20, I was down at the Hall Theatre bright and early — relatively speaking — for an 11 AM showing of Ride Your Wave (Kimi to, nami ni noretara, きみと、波にのれたら), an animated feature from director Masaaki Yuasa. I’d seen two of Yuasa’s previous works,

On Saturday, July 20, I was down at the Hall Theatre bright and early — relatively speaking — for an 11 AM showing of Ride Your Wave (Kimi to, nami ni noretara, きみと、波にのれたら), an animated feature from director Masaaki Yuasa. I’d seen two of Yuasa’s previous works,