A Calm Book for a Mad Time: Inherit The Stars by James P. Hogan

|

|

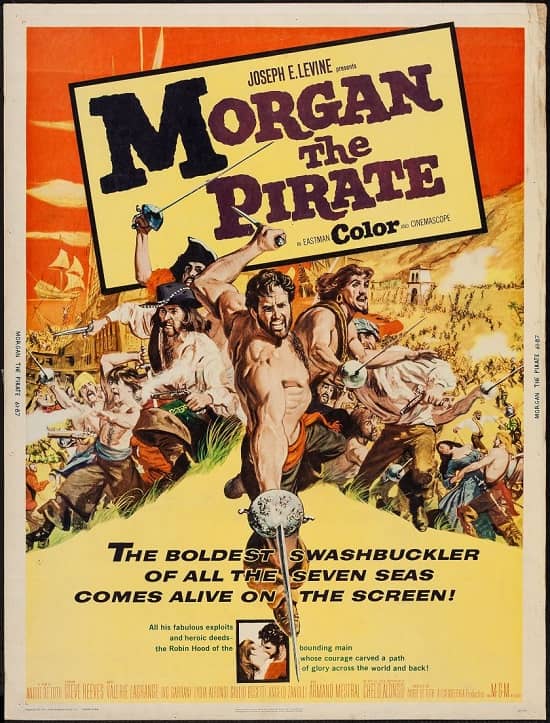

Inherit the Stars (Del Rey, 1990 reprint). Cover art by Darrell K. Sweet

James P. Hogan’s Giant’s Trilogy has been a presence at my parents’ house since the late 70s. Sometimes on the shelf, sometimes on the coffee table, sometimes on the end table. I had to move my mom into assisted living last year and in sorting the books (oh, the books!) into ‘take with her,’ ‘move on,’ and ‘keep for myself,’ I gently slipped them into the ‘keep for myself’ pile, and now, two years later, I have started to read them.

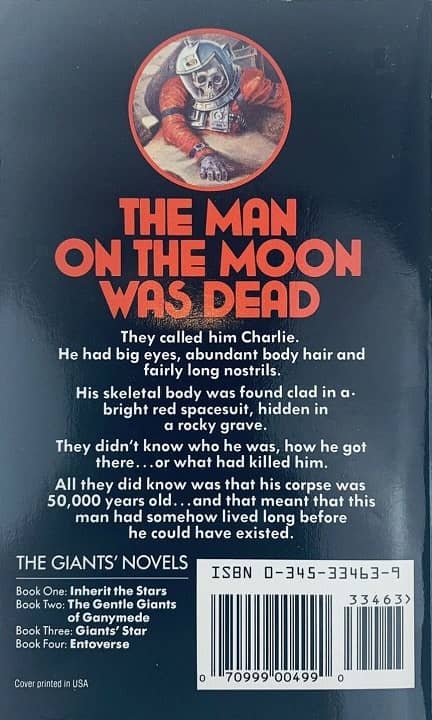

Inherit the Stars is very much a book of its time, and its time is 1976. My views are split: the ideas that make up the book are very good, but the actual story? Dull. There is no real tension, no villain (more on this later), no real action. Nobody’s spacesuit ruptures, nobody’s virgin-launch spaceship has a glitch. This is a book about ideas and that’s it. I sometimes got an image in my mind of Isaac Asimov reading Inherit the Stars and having to light up a post-idea cigarette.

As frequent readers of my reviews will know, I have very little desire to write spoiler-free reviews of 44-year-old books. New readers, be warned.

…