Writing Rogues, Part One: A Study of Batman: The Animated Series

Batman lurks in the dark

I love villains. They’re often at the center of what makes a great adventure story tick. They force our protagonists to take action, to face their worst fears and come out better, to outdo themselves again and again. They push character arcs, drive narratives, and illuminate the differences between regular people and heroes. In short, villains get the story up and out.

Ask an author what the most important storytelling element is and they’ll probably tell you it’s conflict. Conflict occurs when the main character meets a challenge to their goals. In sword and sorcery, that challenge is often a person. While there are the famed man vs. self, man vs. society, and man vs. nature conflicts as well, antagonists are some of the most engaging sources of conflict because they’re human. Or human-like. We’re programmed to engage more with characters than we do with snowstorms or oppressive governing entities.

Batman battles Scarecrow’s hallucinogenic fear toxin

Villains are a special kind of antagonist, one with ignoble qualities. They’re selfish, self-righteous, cruel, and dangerous, often with direct animosity toward the protagonist, if not to the whole of society. Villains can range anywhere on a colorful spectrum from “bad with redeeming qualities” to “straight up world dominators.”

Not all protagonists are heroes but heroes TEND to be the protagonists of our stories. Likewise, not all antagonists are villains, but villains TEND to be the antagonists of our stories.

Bruce Wayne contemplates his Batman identity

So how do you write a good villain? Let’s look at some of the most acclaimed assortments of antagonistic characters in any franchise : Batman’s rogues’ gallery as interpreted by the classic Animated Series.

Harvey Dent is bilaterally scarred, transforming him into the villain Two-Face

Some might think they’re famous because of their gimmicks, and there’s some truth to that. A bird themed thief with a trick umbrella or a clown themed nemesis with a deadly sense of humor give these characters a fun, zany pizazz that’s hard to imitate, even in other superhero stories.

Mad Hatter plots his revenge

But the rogues’ gallery’s success is dependent upon far more than this. The best of them possess other qualities that make them fascinating and entertaining.

Bruce fights the Mad Hatter in his dream world

1. Batman rogues are ironic.

There’s nothing like a little tragic irony, especially if it involves a villain. From Mr. Freeze’s cold-hearted tactics and inability to live above freezing temperatures to Two-Face’s asymmetrical scarring, which he believes forces him to constantly choose between good and evil, irony is everywhere in Gotham. Irony is a staple in fiction and has been since humans first began telling stories. Any fairytale you read is littered with ideas that were culturally ironic in the day, many of which are still. There’s something about irony that has intrigued us humans for millennia. It might not be especially realistic, but damn is it satisfying. Of course, many of us have seen irony so often in fiction that we’re a little tired of it. It’s understandable to be disenchanted with an overused narrative device. But, the best of Batman’s villains are subtle. The irony is understated, below the surface. Maybe irony is the cumin of storytelling, a powerful and complex ingredient that can overpower the dish if you’re not careful. A good example of how to incorporate irony in modern storytelling can be found in the episode “The Last Laugh.” During the climactic battle, Joker’s actions almost cause Batman to fall into a garbage incinerator, but then Joker trips on a rope and nearly fries himself. The moment works because the story doesn’t linger on it and because both instances of near immolation happen rather differently so the comparison is there, but not in your face. So we’re left with just the satisfying notion that The Joker got a taste of his own medicine. Ah, sweet vengeance.

The Joker grins menacingly

2. Batman rogues are human.

Mostly human anyway. At their best, each rogue carries a unique set of skills, philosophies, and motivations. More on that later. The best rogues are driven by personal, internally consistent reasons, just like the hero. Other superheroes struggle more with making villains personal because their heroes are godlike, and as a result, their villains have to be godlike to even pose a threat. If your villain can deflect bullets and survive in the vacuum of space, it’s harder to make them relatable and they often end up just another stony, apocalyptic body-builder. Sure, deific villains can be scary, but how fun are they to watch? The Joker has no world-ending powers. He can’t fly or see into the future. He’s just an evil homicidal clown. But compare his stories to those of Darkseid and see who gets more audience engagement. Darkseid is a god. Joker is a human. Again, we humans like to read about humans. The Joker is on our level so he’s a much more personal threat.

The Title Card to the episode “The Last Laugh”

3. Batman villains are driven.

It’s all about the motive. I find, once I have a really good motive for the villain and the hero, the story begins to write itself, especially when the hero and villain are in a room together. I almost can’t emphasize this point enough. What does the Mad Hatter want this episode? Just to be left alone. And how is he going to do that? By brainwashing his enemies so that they can no longer threaten him. Brilliant! Therefore, Batman’s motive this episode is to escape the Mad Hatter’s scheme. That’s it. This setup is FUNDEMENTALLY personal. On the one hand, The Mad Hatter’s scheme is evil and crazy, but we can also kind of relate to it. We all wish our enemies would just leave us be sometimes. And it’s not like he’s killing Batman this time. He just wants to trap him in an idyllic dream world. Still evil. But, ya get it. And on the other hand, Batman has to figure out he’s in a dream and come to terms with the fact that this perfect reality is all a lie. Even while engaging with his living parents. The Mad Hatter’s motive is simple, intimate, and human. And Bruce’s torment at having to abandon a world where he can live with his parents is relatable and heart-wrenching.

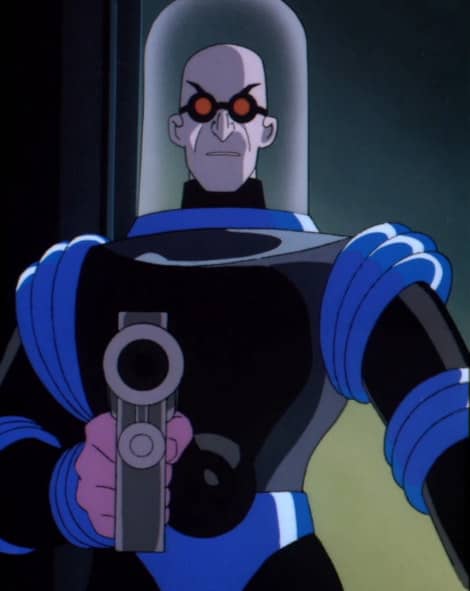

Mr. Freeze aims his freeze ray

4. Batman villains are philosophical.

Every villain in the rogues’ gallery is like a professor of psychology. They each have one or two lessons about human nature they want to teach us. The Scarecrow shows us the importance of fear in our decision-making, and how too much fear can tear society apart. The Riddler shows us that narcissism can drive us to do terrible things and that obsession can be our greatest weakness in achieving our own ends. Mr. Freeze is a lesson about how righteous anger can turn into wanton vengeance if compassion and reason are removed. Stories are more than just stories. There’s always a message hidden beneath the surface that your audience will come away with. You should, therefore, try to understand what that message is and deliberately bend it and shape it into a message you want to share. When it comes to villains, the message is usually an example of how NOT to behave. Conversely, the hero inspires us to do better.

The Riddler explains his puzzle

5. Batman villains tell us about Batman.

This is the most important lesson I learned from studying the rogues’ gallery. The best villains always tell us something about the hero. We learn about the hero’s hopes, dreams, nightmares, and internal struggles through conflict with their respective bad guy. It is crucial that your villains shine a spotlight on your hero’s character. And it works the other way around too. Usually, you can achieve this telling relationship through one of two ways: making your villain the antithesis of your hero, or making them a dark reflection. Either way, they will shed light on who your hero is as a person. Batman villains are masters at this and each one tends to have a unique villain hero relationship because of what they tell us about Batman. Take the Scarecrow for example. Like Batman, he uses fear to exert power over his enemies and shape society. Both even dress up in scary costumes and haunt the night. However, the Scarecrow does it for personal gain and sadistic pleasure while Batman does it to protect the city he loves. Thereby, Scarecrow stories show us Batman’s relationship to fear.

Need more? Okay, let’s try Mr. Freeze. He’s driven by vengeance and love, kind of like our hero, but he has forgone compassion. Batman, on the other hand, has not. Therefore Mr. Freeze stories show us Batman’s compassionate side. How about the Joker? Easy. He’s the opposite of Batman. Law vs. Chaos. Complete selflessness vs. total narcissism. Any Joker story will show us a contrasting Batman feature. Two-Face? This former ally who sees himself as a slave to fate shows us Batman the anti-fatalist. The Mad Hatter? He shows us Batman the advocate of free will. I could go on and on. Whether you choose to make your villains dark reflections or polar opposites of your heroes, the central takeaway of Batman is to always use them as windows into your protagonist’s psychology. And vice versa.

Disfigured Robot Batman contemplates the meaning of its existence

There are some things in Batman’s rogues gallery that we cannot or should not imitate. For instance, the gimmick thing is so intrinsically tied to Batman that even other superhero stories get called Batman ripoffs when they feature psychedelic rogues who are obsessed with nursery rhymes or clocks. Plus, the characteristic cheesy irony of many of these characters just doesn’t hold up to scrutiny outside the genre. If the villain of your sword and sorcery tale is an evil bard named Celeste Piper whose parents died tragically in a flute-related accident, then your audience is probably gonna roll their eyes and put the book down. Not saying you can’t make that work. Just that it’ll make your job way harder.

The Scarecrow advances

Also, let us remember that the Batman comics, like all fiction, were informed by societal prejudice. Many of the original storytellers undeniably held some of the racist, sexist, and, above all ablest viewpoints of their time. I didn’t list any of Batman’s famous female antagonists in my examples because most of them break the very rules of compelling villain writing I was describing. More recent authors have tried to update Batman’s women rogues, but the interpretations vary wildly and generalizations about their character traits and their relationship with Batman become hard to make. Additionally, I was hard pressed to find ANY good villains of color in the rogues gallery. Women and people of color tended to be ignored in early 20th century writing and, when they weren’t ignored, well…let’s just say those stories didn’t age well.

Batman catches the Scarecrow with Robin’s help

I would be remiss if I didn’t discuss the ableism of the rogues’ gallery in a little greater depth. For the most part, all of Batman’s villains are caricatures of specific mental, and sometimes physical, illnesses. In this way, they were a continuation of Western culture’s long-standing demonization of the disabled. The Animated Series took a step in the right direction by humanizing many of the rogues and studying their relatable motives for going bad. In general, it would be unwise and inappropriate to give your own stories a villain with a pop-psychology diagnosis. Making your villains of sound mind and body will also make your stories feel more realistic because, truthfully, most mentally ill or disabled people are non-violent and most crimes are committed by people with no diagnoses.

Two-Face prepares to flip his coin

Caveats aside, I think there’s a lot we can learn from studying Batman’s villains. The fact that they are so beloved to this day, even sometimes outshining Batman and the superhero genre, just shows how appealing they are on every level to the human consciousness. There have been other works of fiction that feature equally memorable villains (Avatar, Gravity Falls, and Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood to name a few), proving Batman hasn’t cornered the market on great villains. That means you can do it too.

Bruce Wayne confronts Batman within his mind

Darian Jones is a writer, artist, and composer embroiled in the animated storytelling medium. The eldest child of acclaimed sword-and-sorcery author Howard Andrew Jones, Darian tends to have many irons in the fire. Currently, that includes drawing the artwork for Reuben Baron’s webcomic, Con Job, writing and editing a personal webcomic, Hellbound, and composing film scores for a variety of projects. Darian loves gothic fantasy, horror, action adventure, and science fiction, with a special affection for villains and antagonists. View more of Darian’s work at darianvincentjones.com.

You know that Batman: TAS holds up better than some of the supposedly adult shows I watched.

I absolutely agree! I still get so much mileage out of it every time I rewatch these episodes. There’s a few other shows like that which I’d like to discuss in future articles, including but not limited to Mighty Max, Star Trek TOS, Avatar TLA…

Excellent article! I was always a fan of villain portrayal in TAS, but you also took note of more than a few points which I hadn’t previously considered. Thanks for posting this.

Thank you for your comment! Yeah the TAS portrayals of these characters are, for the most part, the definitive portrayals in my book. There’s very few characters I think they didn’t do a perfect job with. Maybe I’ll look into those next time. 🙂

This is a great article about a truly good show. This debuted while I was in college and still holds up (and I think for a lot of people, Kevin Conroy is a definitive Batman) — frankly, until *arguably* the Nolan trilogy, the “Batman: Mask of the Phantasm” film that this show birthed was a far better Batman movie than anything that had gone before.

But back to your article: Batman’s Rogues Gallery are certainly archetypes, which different authors have humanized or not to varying degrees, with the decided exception of the Joker, who really needs to exist in contrast to the Dark Knight, as primordial chaos to an attempt to maintain order. I think what Batman:TAS did so well was to actually embrace that while letting the other rogues have far more of a backstory and nuance. This show’s Mr. Freeze is decidedly better than any other, and there were little subversive tweaks (search “Is Harvey Dent on B:TAS white or black and see what comes up! Truth is that he has a certain bi-racial look that becomes more so as Two-Face; I’ll let readers make their own psychoanalytic analysis of the suggestions of being between two worlds and not in either that are hidden therein).

Overall, I’d say the series was far ahead of its peers for its era, and still is in many cases, though surely not all. There has rarely been an attempt by the Batman movies to delve as deeply into the Dark Knight’s psychology, for example, as the series’ best (at least IMO) episode, “I Am the Night”, surely pushing the envelope as far as day time TV would allow a superhero cartoon to go, much as “The Killing Joke” had with comics.

https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x6v0tu4

Your comments about representation in the Batman canon itself, of course, remain true, though I think it interesting that for all the talk in recent years about the “emancipation” of Harley Quinn, it was Batman:TAS back in the 1990s that introduced the character, and far less as a hyper-sexualized toy to the Joker than the character suffered through in comics for years. (Now she’s hypersexualized but independent…I guess that’s…progress?) The Selina Kyle of this series is definitely in the mainstream of the last 40 years (not exactly good, but really not bad, and Bruce is so conflicted), but done well. I don’t recall Poison Ivy really having the sort of depth of the other characters.

Great article — I hope the first of more!

I loved reading your thoughts!

Yes, Mask of the Phantasm remains my favorite Batman movie, with Sub Zero closely following. There’s things I like about the Nolan trilogy, but what can I say? Mask of the Phantasm just fires on all cylinders. If anyone here hasn’t seen it, do so immediately!

Yes, TAS beautifully manages to make its villains as layered and compelling as the main character without compromising their status as villains or Batman’s status as the hero. There’s many episodes in the series, like Mad as a Hatter, which mainly focus on the villains’ pov and their slow, sad decent into evil. Also, I honestly can’t see Two-Face looking any different from this depiction! XD The boyish, McCartney-esque features and the sky blue suit? As a character designer, I love that his design as Dent was already interesting before he became Two-Face. And yes, I always thought he didn’t look necessarily white, though I’d never thought about him being bi-racial. That hope future stories explore that idea more thoroughly (and carefully).

Also yes, I agree! TAS took a lot of steps in the right direction with their female characters. I love its portrayal of Barbara Gordon, Dr. Leslie Thompson, Summer Gleeson, and the ignorant but well-meaning Veronica Vrieland. I also think they improved the humanity of Catwoman and did a decent job with Poison Ivey by giving her environmentalist motives.But, like you said, not my favorite. I just didn’t find their episodes as interesting growing up because they didn’t feel as zany and fun. Then, of course, there’s Harley Quinn, whose portrayal in TAS is the only one I really care about. It’s true! After TAS, despite becoming an antihero, few writers managed to paint her in quite the same complex and layered light. One more I’ll mention is Baby Doll. This original villain was so well-rounded and zany and funny and tragic, I’m shocked few others have even tried to work the character into Batman stories. The ending of her episode STILL makes me cry! But that’s a story for another article.

This is an intriguing article! It makes me consider the Gothic credentials of Batman. Batman is “Gothic”–e.g. Gotham, bats, mansions, criminality, etc.–and the Gothic literature is permeated with the idea of the “villain-hero” or “Miltonic villain” (c.f. *The Monk,* by M.G. Lewis). Or consider *Dracula* (or the vampire trope more broadly): over the course of many texts, the trope oscillates between being quasi-angelic/attractive versus being a profane monster. Anyway, in Gothic culture, the line between hero/villain blurs artfully. I might be reading too much into a comic book hero… but now you me thinking of Batman’s origin story, his epiphany at the bottom of the well, where he must face his own potential for evil/fear: is Batman just a hero who *could have been* a villain? Interesting. Thanks for writing this.

There is actually a Batman storyline called Gothic which deals with a deal with the devil like in the old gothic novels. Spoilers in the link:

https://dc.fandom.com/wiki/Batman:_Gothic

Thanks for your comment! One thing I didn’t discuss in this article was how many of the Batman villains seem to have direct monster movie inspiration. Man-Bat is a living Jekyll and Hyde. We got evil clowns, vampires, mad scientists, and many more. Maybe in the future I’ll do an article about the Gothic inspirations behind Batman’s villains!

[…] Writing Rogues, A Study o Batman: The Animated Series […]