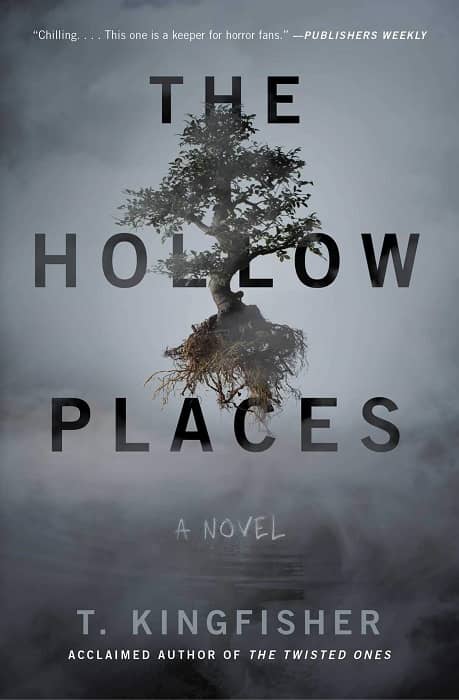

New Treasures: The Hollow Places by T. Kingfisher

|

|

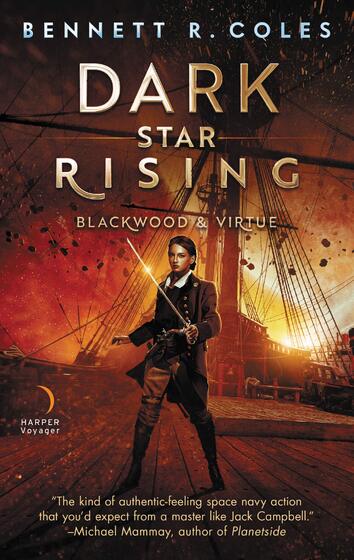

Cover design by Chelsea McGuckin

Ursula Vernon is one of the more talented young fantasy writers in the business. She won a Hugo and Mythopoeic Award for her webcomic Digger, which was hugely popular in the Black Gate offices (reviewed here by both Alana Joli Abbott and Matthew Surridge), another Hugo for her novelette “The Tomato Thief,” and a Nebula for her short story “Jackalope Wives.” She’s also the author of the bestselling Dragonbreath series.

As T. Kingfisher, she writes much creepier fare, including The Twisted Ones and The Seventh Bride. Her latest is The Hollow Places, which Kirkus Reviews calls “wonderfully twisted… The perfect tale for fans of horror with heart.” Here’s an excerpt from the enthusiastic notice at Publishers Weekly.

Kingfisher (The Twisted Ones) imagines the horrors lying between worlds in this chilling supernatural thriller. Recently divorced Kara (aka Carrot) moves in with her uncle Earl to help run his Wonder Museum… Then a hole mysteriously opens in the museum’s wall, revealing a hallway that should not exist. With the help of Simon, the barista from the coffee shop next door, Carrot sets out to discover where the hall leads. On the other end they find a strange world comprised of tiny islands covered in willows and containing concrete bunkers — and a mysterious group of occupants… Kingfisher has crafted a truly terrifying monster with minimal descriptions that leave the reader’s imagination to run wild. With well-timed humor and perfect scares, this one is a keeper for horror fans.

The Hollow Places was published by Saga Press on October 6, 2020. It is 341 pages, priced at $16.99 in trade paperback and $9.99 in digital formats. The cover is by Chelsea McGuckin. Listen to an audio excerpt here, and read a sample chapter at Ginger Nuts of Horror.

See all our coverage of the best new SF and Fantasy here.

Ah, Horror in the time of Covid! It seems almost superfluous, like a feather boa on an ostrich.

Ah, Horror in the time of Covid! It seems almost superfluous, like a feather boa on an ostrich.