Ellsworth’s Cinema of Swords: Disney’s Early Swashbucklers

After the box-office success of RKO’s The Spanish Main (1945) and Sinbad the Sailor (1947), in 1948 Warner Bros. re-released The Adventures of Robin Hood to theaters, where it did almost as well as its first time ‘round in 1938. The rest of Hollywood took notice, and soon every studio had two or three historical adventures in the development pipeline. The postwar swashbuckler boom was on!

Walt Disney wasn’t about to be left behind. With a pile of money parked in European banks, he decided to open a British studio to make his first live-action films, using The Adventures of Robin Hood as the template: historical adventures with broad appeal based on familiar stories from public domain sources (because why pay royalties?). And he hit a home run the first time at bat with Treasure Island.

Treasure Island

Rating: ***** (Essential)

Origin: USA/UK, 1950

Director: Byron Haskin

Source: Disney DVD

Walt Disney liked to adapt well-known classic tales, so when he decided to make his first live-action feature, it’s not surprising that he chose Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, with its child protagonist and adventures in exotic locales. What is surprising is how hard-edged and gritty it is, considering Disney’s later (well-earned) reputation for peddling bland conformist mediocrity. This 1950 film is as tense and dynamic as its pre-Hays Code 1934 predecessor, and just as closely adapted from the novel, though exact choices of scenes and dialogue vary between the two. Moreover, the Disney version is in vibrant full color.

Mickey Reece is a musician turned underground filmmaker with over two dozen features to his credit. In 2019 he came out with Climate of the Hunter, which he directed and wrote with John Selvidge. It streamed on-demand at this year’s Fantasia Festival, and it’s billed as a cross between old-fashioned movie melodramas in the style of Douglas Sirk — what is sometimes called a “

Mickey Reece is a musician turned underground filmmaker with over two dozen features to his credit. In 2019 he came out with Climate of the Hunter, which he directed and wrote with John Selvidge. It streamed on-demand at this year’s Fantasia Festival, and it’s billed as a cross between old-fashioned movie melodramas in the style of Douglas Sirk — what is sometimes called a “

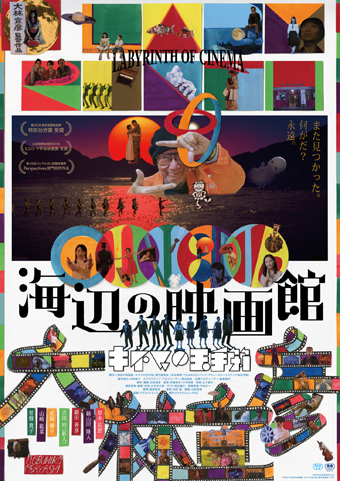

Nobuhiko Obayashi, the director best known for the surreal 1977 horror film House (Hausu, ハウス), died on April 10 this year. His final film is Labyrinth of Cinema (海辺の映画館 キネマの玉手箱), which he wrote as well as directed. Just as visually extravagant as House, it grapples with weightier themes — specifically, the nature of cinema and of war, and how film can be used to protest war. It’s therefore also a rumination on history, specifically the history of Japan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and how that history was depicted in the movies of its time. And Labyrinth gets at these things through the frame of a fantasy story about movie spectators unstuck in time and narrative. Obayashi swung for the fences with this film, a three-hour long experience that feels like a career summation, a director reflecting on his life and craft and art.

Nobuhiko Obayashi, the director best known for the surreal 1977 horror film House (Hausu, ハウス), died on April 10 this year. His final film is Labyrinth of Cinema (海辺の映画館 キネマの玉手箱), which he wrote as well as directed. Just as visually extravagant as House, it grapples with weightier themes — specifically, the nature of cinema and of war, and how film can be used to protest war. It’s therefore also a rumination on history, specifically the history of Japan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and how that history was depicted in the movies of its time. And Labyrinth gets at these things through the frame of a fantasy story about movie spectators unstuck in time and narrative. Obayashi swung for the fences with this film, a three-hour long experience that feels like a career summation, a director reflecting on his life and craft and art.

Day 5 of Fantasia began for me by watching Simon Barrett give bad career advice. Barrett’s the writer of horror movies such as The Guest and You’re Next, and he took questions from an online audience for what turned out to be more than two hours in a self-effacing discussion about how the modern movie industry works (or fails to), and how aspiring filmmakers can prepare themselves for entering that world. It was a funny, detailed, and generous discussion, which

Day 5 of Fantasia began for me by watching Simon Barrett give bad career advice. Barrett’s the writer of horror movies such as The Guest and You’re Next, and he took questions from an online audience for what turned out to be more than two hours in a self-effacing discussion about how the modern movie industry works (or fails to), and how aspiring filmmakers can prepare themselves for entering that world. It was a funny, detailed, and generous discussion, which