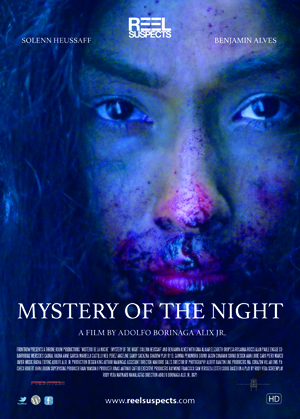

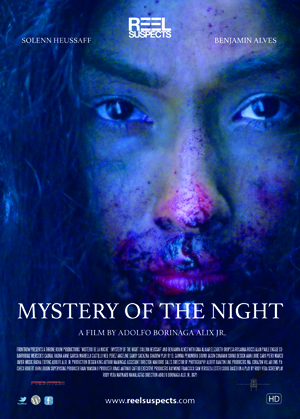

My fourth film of July 14 brought me back across the street to the De Sève Theatre for a tale from the Philippines, Mystery of the Night. Directed by Adolfo Alix Junior, it’s an adaptation of a play by Rody Vera called Ang Unang Aswang (The First Aswang). As written for the screen by Maynard Manansala, it’s a meditative story that doesn’t betray its stage origins in the slightest, a deliberately-paced visual spectacle about colonialism, magic, and the wilderness.

My fourth film of July 14 brought me back across the street to the De Sève Theatre for a tale from the Philippines, Mystery of the Night. Directed by Adolfo Alix Junior, it’s an adaptation of a play by Rody Vera called Ang Unang Aswang (The First Aswang). As written for the screen by Maynard Manansala, it’s a meditative story that doesn’t betray its stage origins in the slightest, a deliberately-paced visual spectacle about colonialism, magic, and the wilderness.

After an introduction told in the form of a shadowplay, the film proper begins in the 19th century, when Spain ruled the Philippines. There is a sin and an attempt to cover up that sin; we see these things, but the main dramatic action of the film takes place years later. The victim’s daughter (Solenn Heussaff) has been raised by forest spirits in the jungle. Grown to an adult who knows no human language, she meets Domingo (Benjamin Alves), the son of one of the men responsible for the cover-up; he, trespassing into the domain of the spirits, names her Maria. What happens between them, and the transformation she undergoes near the end to bring justice, forms the main part of the movie.

It’s difficult to summarise the film because the movement of the plot is relatively simple, but for that reason deserves to be experienced relatively unspoiled. There is a stately rhythm to events, which unfold simply, one thing leading to another with dreadful inevitability. This is by no means a plot-oriented movie, but I’m not sure it would be precisely accurate to call it centred on character, either. It’s driven perhaps by theme and visual sense as much as anything, and if that sounds unpromising, in practice I think it works surprisingly well.

The themes are deep and interconnected, if perhaps schematic. The original sin that drives the story is brought about and covered up by the collusion of the colonial church and the colonial state, male structures acting against a low-status woman. Powerful men from a built-up city make an incursion into the wilderness, and despite their best efforts, indeed ironically because of them, create a kind of innocent yet powerful female force within the wild forest. That woman, Maria, ends up being given her name by Domingo, and both of those names are symbolic; his choice for her says something about his character but is perhaps best understood as irony. In any event Maria herself is a creature without language — specifically, perhaps, without the language of colonial oppression. If their initial encounter is Edenic, in civilisation Domingo reveals himself to have a patriarchal attitude, using things and people for his convenience. This leads to Maria’s transformation, and violence that resolves itself with certain myths having reasserted their powers and certain other mythologies exposed as powerless.

…

Read More Read More

My fourth film of July 14 brought me back across the street to the De Sève Theatre for a tale from the Philippines, Mystery of the Night. Directed by Adolfo Alix Junior, it’s an adaptation of a play by Rody Vera called Ang Unang Aswang (The First Aswang). As written for the screen by Maynard Manansala, it’s a meditative story that doesn’t betray its stage origins in the slightest, a deliberately-paced visual spectacle about colonialism, magic, and the wilderness.

My fourth film of July 14 brought me back across the street to the De Sève Theatre for a tale from the Philippines, Mystery of the Night. Directed by Adolfo Alix Junior, it’s an adaptation of a play by Rody Vera called Ang Unang Aswang (The First Aswang). As written for the screen by Maynard Manansala, it’s a meditative story that doesn’t betray its stage origins in the slightest, a deliberately-paced visual spectacle about colonialism, magic, and the wilderness.

I saw my third film of Sunday, July 14, in the big Hall Theatre. Paradise Hills was introduced by director Alice Waddington, who spoke about her love for Lord of the Rings, Dungeons & Dragons, and The Neverending Story, and how she wanted to make something that reflected her and her friends. It was an interesting way to set up a fine film that continually did unexpected things.

I saw my third film of Sunday, July 14, in the big Hall Theatre. Paradise Hills was introduced by director Alice Waddington, who spoke about her love for Lord of the Rings, Dungeons & Dragons, and The Neverending Story, and how she wanted to make something that reflected her and her friends. It was an interesting way to set up a fine film that continually did unexpected things.

I saw my second movie of the day of July 14 in the Fantasia screening room, where critics can watch a movie on a large computer monitor at a time convenient to their schedules. And indeed scheduling had brought me to the screening room to fill a gap between two other films I wanted to see. Note then that I did not see the film I’m about to describe in a theatre; I don’t think the way I watched it affected my reaction, but it’s perhaps best to give it the benefit of the doubt.

I saw my second movie of the day of July 14 in the Fantasia screening room, where critics can watch a movie on a large computer monitor at a time convenient to their schedules. And indeed scheduling had brought me to the screening room to fill a gap between two other films I wanted to see. Note then that I did not see the film I’m about to describe in a theatre; I don’t think the way I watched it affected my reaction, but it’s perhaps best to give it the benefit of the doubt.

In reviewing the movies I see at Fantasia I like to mention the theatre in which I see a film, because the room the film’s screened in often gives a hint about the movie’s nature. The smaller De Sève is often a venue for indie cinema and lesser-known pictures. The larger Hall will usually hold more obviously popular movies, meaning a lot of action films and blockbusters. This is not inevitable, and there are a number of reasons why something you’d think you’d see in one cinema gets hosted in the other. But the two theatres do have their own personalities, and sometimes you watch a movie that fits the personality of the place perfectly.

In reviewing the movies I see at Fantasia I like to mention the theatre in which I see a film, because the room the film’s screened in often gives a hint about the movie’s nature. The smaller De Sève is often a venue for indie cinema and lesser-known pictures. The larger Hall will usually hold more obviously popular movies, meaning a lot of action films and blockbusters. This is not inevitable, and there are a number of reasons why something you’d think you’d see in one cinema gets hosted in the other. But the two theatres do have their own personalities, and sometimes you watch a movie that fits the personality of the place perfectly.