Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction, November 1979: A Retro-Review

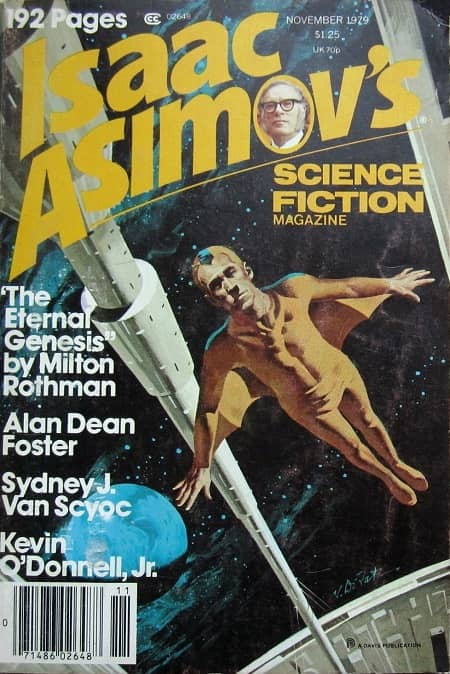

Asimov’s Science Fiction, November 1979

Edited by George H. Scithers

Published by Davis Publications. 196 pages, $1.25

I heard you missed me! I’m back!

Technically, this is Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine (now known as Asimov’s Science Fiction). It was a refreshing change of pace after Galileo’s ‘story behind the story,’ and Analog’s massive book review. Asimov’s was pretty much fiction and nothing but fiction. 192 pages of it, as the cover advertises!

Also advertised, Dungeons and Dragons — and not ‘Advanced’ D&D, but the original. Takin’ it back! Also, as I’ve said elsewhere, taking readers away from sci-fi magazines in the long run.

Editorial, The Dean of Science Fiction, by Isaac Asimov. Dr. Asimov has a complex relationship with radio interviews. He’ll do them, but he doesn’t really enjoy them. His annoyance was increased as the interviewer kept referring to him as “the dean of science fiction” — which Asimov does not believe he is.

The core of his argument is that ‘deans’ are often based on years of seniority, of which Asimov, while in the game for a long time, does not consider himself to qualify. After some parsing of phraseology, it wouldn’t do to have a writer who wrote a lot but the writing had no impact, nor would it do to have an author who wrote a very influential story but only wrote that one story, and finally they have to have been at it longer than Asimov himself. Asimov gets to the meat of it, announcing who he thinks is the Dean of Science Fiction, and his four runners-up to the office.

1. Dean of Science Fiction: Jack Williamson. In the game since 1928, current President of SFWA, second person chosen as a Grand Master of Science Fiction.

2. First Runner-up: Clifford D. Simak. In the game since 1931, third person chosen as a Grand Master of Science Fiction.

3. L. Sprague de Camp. In the game since 1937, fourth person chosen as a Grand Master of Science Fiction.

4. Lester del Rey. In the game since 1938, the guiding spirit behind Del Rey books, on the sunny side of 70.

A notable absence in the list Robert Heinlein. Why? Because he’s been in the game since 1939 (behind Dr. Asimov by a year and a half). Asimov makes no secret that Heinlein may be the best science fiction writer (as voted on fans, readers, and teachers), and he was the first Grand Master of Science Fiction.

Asimov ends his editorial with a suggestion that Lester del Rey be named the next Grand Master. His campaigning was for naught, as the next Grand Master was Fritz Leiber, in 1981. Lester del Rey did get his title in 1991.

A quick sidebar, it is sometimes easy to forget that the internet has not always been around, and that submissions guidelines have not always been at the touch of a button. In fact, back in the 1970s you had to contact the magazines themselves and ask for their guidelines; usually by sending a SASE envelope to them. Magazines must have spent a fortune on copying.

Column: On Books, by Baird Searles. That part above, where I said that Asimov’s didn’t delve too deep into the books? Not quite true. Baird reviews bunch of books, and starts off prescient.

“[Richard Cowper’s The Road to Corlay] is set at the beginning of the fourth millennium A.D; a thousand years before, the Earth had been subjected to an inundation caused by the melting of the ice caps, in turn triggered by atmospheric changes brought on by pollution. […] Cowper’s writing is smooth and convincing; and what could have been a hackneyed, overdone setting seems fresh in his hands.”

The Dragon Lord, by David Drake. An Arthurian re-telling in a barbaric dark-age Britain; Baird approves!

The Web Between the Worlds, by Charles Sheffield. Baird avoids a comparison between this and Clarke’s The Fountains of Paradise and praises the way Sheffield fits all the pieces together.

Mistress Maringm’s Repose, by T.H. White. Young Maria discovers a lost colony of Liliputans and must protect them from the harsh reality of the world and her averous relatives. Baird calls this one a classic.

The Wizard of Oz Series, by L. Frank Baum. Baird delves into his re-read of the Oz series. He is still a fan!

Column: The SF Conventional Calendar, by Erwin S. Strauss.

I include this one because 1979 was a golden age for meeting the greats of SF writing at conventions. Jack Williamson at MileHiCon! Ursula Le Guin at OryCon! Harry Harrison at MapleCon! Robert Silverberg at InterVention! Asimov at The Future Party! A heady time.

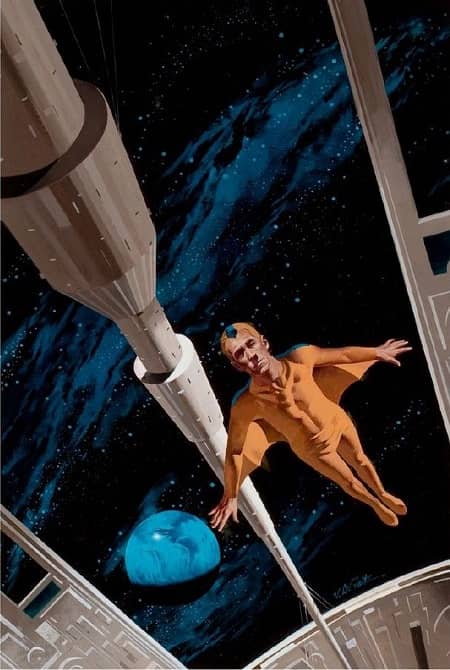

Vincent Di Fate’s cover art for “The Eternal Genesis”

Fiction, “The Eternal Genesis,” by Milton Rothman, artwork (including the cover) by Vincent Di Fate. Jim Kincaid has problems, man. He is a gifted 20-year neural artist, essentially a one-man video/movie making machine. Except he’s run into a bit of a block, his latest tale about humans escaping the death of the universe and attempting a re-settling of the new universe, but in each draft the new universe is fundamentally inhospitable to beings/matter from the old universe. That dog don’t hunt!

“It’s not a bad idea,” [May Wheeler, his agent] said, grudgingly, “but the customers want an upbeat ending. The characters have to get themselves out of their jam” [and] “You have this story set some billions of years in the future, when the universe has turned around and is collapsing instead of expanding. But your characters are completely human, with ordinary American or European names.”

Kincaid is an inhabitant of Lagrange Station, was born there, and is like 7 feet tall, all bones and joints, and not, it turns out, very successful with the ladies. While the ’69 set of SF hinted at a lot of sex, and the ’79 set has been a little more blunt about it, “The Eternal Genesis” is the first story to just come right out and talk about porn; as in, maybe Kincaid should just digitize his lurid fantasies. Running into the hot babes that he didn’t stand a chance with in high school doesn’t help either. Nor does the computerized therapist — although the therapist does help in a ‘whatever is left must be the answer’ kind of way.

The story doesn’t resolve by Kincaid getting laid, as much as it does a lower-intensity friendship with one of the ladies, Tina, and an exciting and near-fatal flying excursion. The man just needed a little excitement to beat the odds!

While a good story on its surface, one of the best things about “The Eternal Genesis” is that it manages to be a story about a writer writing that doesn’t make you hate each and every person involved in its creation. It is also pretty cool to see the various ways Kincaid changes his fundamental story and simultaneously finds new ways to make the universe inhospitable, from antimatter universes to a universe where time travels backwards, he subconsciously screws his characters at every turn!

Rothman, physicist, writer, skeptic and fan, was one of the founders of 1936 Philcon.

Fiction: “The Erasing of Philbert the Fudger Part One,” by Martin Gardner. I’m not sure if this is really a story, or more of an ongoing column of logic puzzles. Philbert X1729B was found guilty of fudging research data and sentenced to be “erased” — having his memories wiped and then re-trained by society. The robot judge states that Philbert will be erased at 3 pm on one of the six days of the next week, starting with Monday, and that he’ll be informed by 10:00 am on the day of his erasure. Philbert askes the judge if it could just tell him the day now, and the judge repeats that he cannot and Philbert will not know the day of his erasure until he is told at 10:00 am the day it will happen.

Philbert thinks he sees a way out — at least an opportunity to show that the logic of the robo-judge is flawed and therefore he can get a mistrial and maybe get a newer robo-lawyer.

It is the long way around the barn to set this one up. The story/puzzle doesn’t read all in one go, instead asking the reader to think on it a bit and pick it up later — a policy I’m gonna follow!

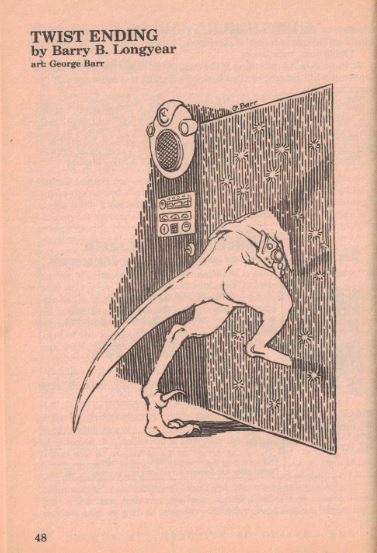

Fiction: “Twist Ending,” by Barry Longyear, artwork by George Barr. This story is mostly an example of how not to write about writers writing. Set up as a dialogue between the writer and his character (I think). Clever quips are exchanged and exchanged again. Such things do not do much for me, so I was glad that this story was short. One thing I did find interesting about the story was that it was about dinosaurs, and in 1979 the cause of the extinction of the dinosaurs was still up in the air.

Fiction: “The Raindrop’s Role,” by Kevin O’Donnell, Jr, art by Karl B. Kofoed. Henry Cooper has come to the planet Nmentror to teach English to the indigenous intelligent natives, the cat-like Nmentrorians. At least, that’s what he’s doing on the surface, but underneath he’s trying to get the natives to question their long-held beliefs and traditions — which are often seemingly unnecessary and brutal. For example, the kittens fight each other to the death at the slightest provocation, which really ruins Cooper’s first date with Jenny, a naïve Terran out slumming from Embassy quarter.

She permitted herself to be led into Cooper’s room. Her face was slack; her eyes, glazed with shock. “Nobody came, nobody helped.”

“They never do, not even the mothers.” And that indifference… he had a theoretical understanding of what they’d just observed, but for the life of him, he couldn’t empathize with any mother, even one of several litters of fraternal quadruplets, who could stand to see three-fourths of her children murdered by each other. “It’s just their system, that’s all. Happened a dozen times since I moved in.”

“But why,” she wailed, turning to watch him close the door. Her eyes clung to him, but not for support. There was fright in them, and wariness.

“Call it, uh… culturally stanctioned natural selection — survival of the fittest. The Nmentrorians despise weakness — you know that that. This way — ” he nodded at the latched door “ — they get the toughest genes into the pool.” Involuntarily, he shuddered. “It seems inhuman, but so are they. And remember, a thousand years ago, Terran mothers buried at least half their children, if not more. It’s…” he groped for the word “…expected.”

What makes this story work is that these are not just sorta-Klingons, fighting each other at the drop of a hat, there are very specific stages. The kitten-murdering-kitten stage, leads to the put-a-cadre of juveniles into a room and not feed them anything but plague rats who will f-them up if they eat them. Take those that didn’t eat the rats, put them through a separate set of trials to pick one to be Lord, let the Lord mate with five females of his choice and then castrate him.

The thing is, the Nmetrorians totally buy into this, they don’t try to help their children, they don’t try to game the rat test, nor do they resent the adults that fail that test, and they all get along with the Lord who gets to bang their females. Nobody resents anybody, and they even find the emotional maturity to tolerate Henry’s constant pestering and questioning.

And the great thing about the story is that Henry Cooper is a bit of spy on a trojan-horse mission to get the natives to question their long held beliefs and traditions.

The story has a few rough spots. Firstly Jenny is just there so that Henry can explain the Nmetrorian society — I just don’t buy the idea that someone would fly to a planet and live in an embassy and not know the first freakin’ think about the natives. Also Henry, as an English teacher, seems to embody all the annoying behaviors of every annoying English teacher you ever had. Constantly berating his students for not speaking English in his class. Constantly pestering them about their beliefs and trying to get them to expand their minds.

Which may go a long way to explaining why he fails so spectacularly in his trojan horse mission. Basically, he calls it in when he finds himself going native, grumbling disposing of the dead kittens in the hallway instead of waiting for them to rot and their mothers do it.

Perhaps I’m reading too much into it, but the final lines of the story bring up a huge question mark:

“There is an alternative,” said Cooper, with his hand on the brass doorknob.

“Revolution?” He snorted angrily. “We don’t do that kind –”

“No.”

“What, then?”

In a voice so soft and tired that it was almost a whisper, Cooper said, “We could always let them run the galaxy.” Then he was gone.

Eh? Eh? Is he taking part in the long tradition of English teachers complaining about their administrators, or has he really gone native? And if he has gone native is it because he admires the Nmetrorian’s brutality, or their clear-cut honesty?

Kevin O’Donnell Jr. was also a big name in both fandom and writing, chairing awards committees and publishing several novels. November 1979 was a good month for O’Donnell, as he was also published in Analog (“Old Friends”).

Poetry: Tanka for the SUNSAT project, by Robert Frazier (included in its entirety)

Engineers of night:

Transmute steel from meteors,

Play sun-power go,

Build rock gardens of mirrors,

Teach the lotus to trap light.

I only found this poem to be okay, but there was a bit of cosmic synchronicity- the ‘sun-powered go’ reference and the fact that at the time I read this I also was catching up on the news about the AI AlphaGo beating human masters.

Fiction: “In Spring a Livelier Iris,” by Ruth Berman, art by Hilary Barta. Mother Joyce Varennes has a heavy space-Catholic cross to bear. Especially difficult in the higher gravity world of Zelb. It’s tough out there for a female priest, what with the colony being mostly Indian and Chinese, who are not that into the whole Catholicism thing. Then there are the Zelbs themselves, whose innocent curiosity are a real drag.

They crossed themselves, they genuflected with one foot leg or both… and they could not understand why she refused them the sacrament, which she did first on the grounds that they had not made confession, and then (when they flocked to the confessional and confessed to eating forbidden fruits, breaking the Sabbath, lusting after the youth of heathen tribes, and casting the first stone) on the grounds that she could not give them the sacrament without a ruling from her superiors. She wanted to say it was on the grounds of making false confession, but was afraid of giving offense. Besides, she wasn’t sure it was so.

Easter is coming up and the Zelbs are really wearing her down with their questions. She is getting some unwanted romantic attention from Dr. Liang Chien, and as she is the only priest on the planet, she has nobody to confess her various sins (mostly annoyance and slothfulness). In fact, as there are not that many religious humans on the planet, her only practicing friend is a Jewish man, Bernie Stein. In an interesting twist, as the only Jew on the planet, Stein is, by default, the only Rabbi.

They talk religious topics. Are Toadcows kosher? Are the Zelbs an unfallen species? And oh, the calendars! How do you get the religious calendars to jive on an alien planet? Their discussions are interrupted by one of the Zelbs, named Clearstep, who wants Mother Varennes to do another Good Friday Mass tonight. The Zelbs she has been preaching to are greatly interested in the motifs of death and rebirth she’s shown them, and it all seems to be in juxtaposition tonight. Oh, and they are interested in the Jewish Seder, too, and they’d like Stein to run that ceremony before the mass.

I’m pretty sure you can see where this is going, yet Berman manages to still make it shocking when Mother Varennes realizes that oh yeah, the Zelbs are totally whipping Stien as they force him to carry a cross up the hill so they can crucify him and see if he comes back from the dead. She breaks several rules, a lot of protocol, and a couple of laws and pulls off a stunning bicycle-based rescue.

Berman really does good work on this story, setting up the Chein-likes-Varennes, but Varennes-kinda-likes-Stein, and Stein-won’t-say-one-way-or-another, and yet the three humans are united in their opportunism to get what they want from the aliens (the zelbs will be happy to let Chein talk to their scholar circle, if he can just help them convince Varennes to set up a mass), plus religion is usually not a thing in most sci-fi, unless it is the odd ceremonies of the aliens, and this story manages to swim against the current, and do it well.

Ruth Berman is still alive and writing, although it appears to be mostly poetry these days.

Fiction: “From the Lunatech Admission Committee,” by Sharon N. Farber, art by Freff.

The College of Physick and Chirurgery was founded in 1837 by Baron Victor von Frankenstein, for “Presons of like mind who have been most foully Persecuted by the common Universities of the Continent.”

After 500 years of educating Mad Scientists, and bouncing around the World before being driven out by pitchforks and torches and finally sets up on the moon. It’s a pretty funny article — something between Girl Genius and Space 1999.

Fiction: “Furlough,” by Skip Wall, Art by Val Lakey.

Humanity has been fighting wars in space, with genetically modified soldiers doing the dirty work. One such soldier, Assault Sergeant Charles Xavier Dawson, has come to Earth, Oregon, to tie up some emotional loose ends. A giant man-mountain, like they all are, he is hesitant because this challenge is far more emotional than physical.

Dawson wished someone from the Regiment were here, even if they just waited for him out here on the highway. Kascinski, or Ford maybe. They would have no comforting words, but the presence of their massive bodies, the steady gazes, the reminder of countless hours spent together since they were children, in play yards and training and mud and falling through the purple skies of enemy worlds and bloody terror under M’techna barrages, the faint smell of camphor from the little-used Dress Bravo, travelling uniforms, Ford’s cold, chewed-to-death cigars, Kascinski’s broad, ancient childhood scar never matched in combat… Dawson could draw strength from these familiar things. But they weren’t here, of course; not even his own shadow was here to accompany him.

But he’s not here for himself, or any of the other Soldiers. Dawson is a rare case, a Soldier who was friends with a Norm(al) human. And he’s come to Oregon to give some bad news to the Norm’s parents.

A low yield, high radiation burst had bathed everyone on the bridge in a shower of neutrons.… Techfive Sanderson had received third degree burns over sixty percent of his body. He had held on long enough to suffer from both the burns and the radiation. Dawson had visited him in sickbay on the Roma. Sanderson had been a doped up, charred mess. There was little the Meds could do with him; with any of them. Jamie had never spoken, but Dawson was sure he had recognized him.

The Cincinnati was hit by a chance shot, a torpedo. Jamie and the bridge crew were killed instantly. He died at his post, and didn’t feel a thing.

He delivers the news and a few personal items. There is uncomfortable talk, Mr. Sanderson did his his time in Regional Upper Atmospheric Defense Command, although RUAD is old news at this point, what with humans driving the M’techna back to their colony planets.

You know when I mentioned ‘genetic engineering’? It isn’t the chrome and white plastic laboratory type of genetic engineering. No Attack of the Clones set-up going on here. It’s really more of a selective breeding program. And for that you need women, and you need secrecy and a society of Soldiers that won’t ask questions and won’t do exactly what Assault Sergeant Charles Xavier Dawson has used a year of backpay to bribe and do. He was just going to stop with knowing that Jamie was his half-brother, be content with that, but that was before the torpedo and the radion and the gentle lies.

Fiction: “Flamegame” by Steve Perry, art by Ron Miller

The race of the N’terstitchi are said to have the key to a remarkable knowledge- the soulknow, which is kind of a zen enlightenment thing. Teela, a dance instructor feeling the first tinges of age (I feel you, sister!) wants that knowledge. The price? Free! You just gotta play, and survive the Flamegame — a wonderfly sadistic challenge, flying a stripped-down hopper over an active volcanic hellscape whose only living inhabitant is a kind of armored asbestos-skinned cow.

This probably would have been a better story if it hadn’t been quite so predictable, and if it hadn’t been paired with “The Eternal Genesis” — because they have the same near-death-experience-opens-your-third-eye kind of thing going on. Teela’s backstory was probably the best part about the story — the future is pretty good, and Teela’s in a pretty good part of it, but there is still a void in her life, one that she wants filled with this kind of esoteric experience.

Steve Perry is a pretty big name in SFF, having written (or will have written) Conan, Star Wars, and Alien vs Predator novels, as well as number of TV scripts for various cartoon series.

Fiction: “The Fare,” by Sherri Roth, artwork by Karl Kofoed.

In a future where all travel is done by transport booth, one old woman has an overwhelming fear of the technology, and has been trapped in the relentlessly windy city of future Chicago for over 30 years. A young boy named Seth befriends her and unravels her story, and discovers that while her fears may be overwhelming, they are far from irrational. Corin was one of the people who invented the transport booth, and carries its awful secret.

The future the story presents is quite interesting. A ten-year old with enough psychology education (because they do that, in the future), to see something remarkable and interesting with the old woman, Corin, and her obvious fear and loathing of the transport booths. He talks with her, and she won’t budge on it, and so he uses that old standby to get people talking — booze! Don’t worry, he’s had a parental permission card since he was eight.

“It all took a phenomenal amount of energy, but we had that too. The remaining problem was to find a way to transport the atoms after we broke the molecules down. Until it occurred to someone, why transport them?”

“How else would you move the person?”

“You wouldn’t. You’d measure everything, and then reconstruct an identical person at the other end. It’s be much easier.”

“That’s ridiculous. What would you do with the original person?”

The wrinkles on Corn’s face settled into the well-worn lines of a bitter laugh. “That was a problem. We considered cyanide, but settled on electrocution.”

“You mean you killed them.?

“Kill, seth. It’s present tense. When you walk into a transport booth today you are electrocuted. Murdered. Your body is broken down into its constituents and used to assemble other bodies transporting to your origin.”

“But that’s illegal.”

“[Technically, no.] After all, an identical you is put together at the other end. A person who is legaly you and doesn’t differ from the original in any discernible way.”

There is a big cover-up about the whole thing, with the threats and the bribery, and Corin and a handful of other people have been in on it from the start. And, as the transport technology took over, it pretty much drove out all other transport methods, no cars, no trains, and that’s why Corin is stuck in future Chicago with no way out.

This is a bit sobering to Seth, who has already used transporter booths multiple times in his life. But, as mentioned, he is a youthful humanologist and, honestly, having unraveled the horrible secret of the transport booth is really on the first half of the problem — the second half is Corin’s unreasonable fear of the booths and her helplessness at being trapped in a city she doesn’t want to be in.

The solution is pretty simple, if one is young and strong enough to force an old woman into a transport booth with a prepaid one-way trip to her Kansas hometown — which Seth happens to be!

Corin fights like hell on the Chicago end, but once in small town Kansas, still hopped up on adrenaline with broken and bleeding fingernails, well… that wasn’t so bad. And, well, since she had already technically just died a few seconds ago… heck, she could do it again! Paris, here I come!

While there were a lot of good things in this story, there is a weirdness to the future that Ms. Roth posits, with Seth being educated in a very different way than we are. And the interactions between the two characters were very well done. Also, in 2017 I wrote a story using essentially the same conceit!

Fiction: “Autumn Sunshine for More Joost,” by John Morressy

As a young writer you might have heard that it is unwise to write about writers writing. Stories like this are exactly why you wouldn’t want to go down that road. I suspect, but I cannot prove, that the story was just the right length for the physical hardcopy needs of the issue.

Of course, it turns out that John Morressy had a long and successful writing career so what do I know!

Fiction: “The Sapphire as Big as the Marsport Hilton”, by John Ford, art by Alex Schomburg

Another very short story. McKee and Rampian, asteroid miners, are investigating a remarkable find — a 15 Km wide asteroid with a 1.5 Km wide crater on it, and the crater is lined with mirrors and the mirrors focus the sun’s rays on a massive sapphire spike. The story is weighed down by waaaay too much witty banter, but it becomes apparent that the eccentric orbit of the asteroid changes the focal point of the light on the sapphire, moving up and down it over centuries and burning away all the impurities. And badaa bing, it’s the business end of a massive sun-destroying laser, built by someone or something as a failsafe in the Sol system.

Fiction: “Sharing Time in the Gallery,” by Sharon Webb, art by Alex Schomburg.

Martin Crewmaster is a small-time grifter and his latest scheme is passing off a forgery of a masterwork of 20th century subliminal advertising. His targets, however, are two Ll’Hh telepaths. He’s got a plan, the mental repetition of a nursery rhyme to throw them off the trail. They Ll’Hh are not quite what we would call art dealers:

“We buy lessons-learned that we motivate toward,” said the aline. “You would call them pictures,” A rubbery finger moved and pressed a button on the desk panel. “I have summoned our resident artist. He is a supremem motivator, and I value his judgement.”

“Motivator?”

The plastiline head nodded gravely. “Creativity is, as you must know, a composite of lesson-learned and motivation toward.”

A blank look passed over Martin’s face. He felt like that character out of Medieval Lit., Alice at the mad tea-party. “Of course,” he bluffed.

While the aliens debate among themselves about the merit of Martin’s art, they let him roam around in their gallery, and being telepathic aliens their artwork is actually a kind of recorded telepathic experiences. And much like Alice in Wonderland, Martin gets pulled into the experiences and can’t really escape. It makes him realize that he could be the artist he really wants to be, if he just drops the grift.

His experience, of course, is the piece of art that the aliens are actually looking for, so all is good.

Sharon Webb went on to publish several novels in the ’80s.

Fiction: “On the Midwatch,” by Keith Minnion, art by Keith Minnion

Newly minted Lieutenant Junior Grade Charlie Midwich is on his first stint as Officer of the Deck for an unnamed US navy ship in the north Atlantic. Things are going well, they are tracking another ship out in the darkness, and then they pick up another thing, too fast for a ship, but too low for a plane, and too big to be anything but a ship, steaming toward them fast.

Keith Minnion was a naval officer and so there is a lot of navy jargon going on, almost an impenetrable code for the uninitiated (like me), but through it all there is a good sense of suspense, of young Charley confronted with a thing that shouldn’t really be, and getting a weird vibe that the whole thing may be some kind of hazing operation. Whatever is going on, it’s honestly above his rank to deal with so he swallows his pride and gets the Captain up, who calmly takes over.

“Tell CIC to turn off the sonar, Willoughby,” the Captain said then. “We’ll end up waking the whole damned ship.” He went to the bride windows. “Ahah,” he said.

“Sir,” Charley began. “It’s-”

It had surfaced. It was a black mountain, rimmed with orange light. There was movement across its surface, things scurrying to and fro… there was the sound of horns, of a huge cathedral organ in a all-encompassing ear-blasting dischord, vibrating the Bridge window glass…

“Right full rudder, helmsman,” the Captain said, calmly, through the sound. “Steady on 090.”

The Captain calls Charley into his office and says that none of this happened. None of this ever happens. And since it didn’t happen, there is no reason to discuss it outside of the handful of bridge-crew and operations officers who are already in the know about a thing that doesn’t happen.

Given all the on-bridge jargon, I’m not 100% sure what was really happening. I think that everybody else in the bridge is in on it, this weird secret thing that they’ve been keeping secret, but maybe Charley deviates from the usual course and nobody can tell him not to do it. Or something. Anyway, it was interesting for the claustrophobic vibe going on.

Fiction: “Mountain Wings,” by Sydney J. Van Scycoc, art by Ron Miller

There is trouble in the valley, Gera and her Grandmother find that three of their thirty eight sheep are missing. Some predator has been coming off the mountain and killing them. Could be a snow-panther, could be a crag-charger, but because whatever it is skinned the sheep before eating it it must be a breeterlik — a yeti-like thing with massive claws, double-hinged jaws, and a propensity to spray digestive juices from its belly-sphincter.

Gera heads up mountain Terlath, above whose jagged peaks fly the silver wing birds, the re-born spirits of the heroes of the valley. She has nothing but desperation and her faith that the power of the mountain will sustain her.

Which turns out to be a load of bunk! She calls on the magic of the mountain and gets nothing! A lucky jab through the belly-sphincter and quick, brutal pull on the first set of arteries she finds makes short work of the breeterlik.

She also discovers the silver-wing birds are just birds, hatched from eggs like other birds. Secrets and lies! It becomes pretty clear during the story that these poor humans are stranded on some alien planet. There are hints that people don’t live long and Gera’s grandmother explains that well, yeah, when there are dangerous predators you send the kids. And you back it all up with the weird mythology about the silver wings.

Gera’s outraged, at first, but then she comes around. Which was very weird, especially since she knows that this trail of lies also leads to a trail of corpses — including Gera’s own friends. But still she doubles down on the superstition — she’s gotta keep the secret or everyone will be as heartbroken as she is, and if they can just hang on a bit longer they will eventually be rescued by the real silver wings (spaceships).

I’m not sure what, if any, the ‘message’ was. It was an odd story, and I got a feeling that some important parts might have been cut.

Sydney J. Van Scycoc went on to write a number of novels through the ’80s.

Fiction: “Gift of a Useless Man,” by Alan Dean Foster, art by Karl Kofoed

Pearson is in a bad way. His ship is crashed, he’s got a broken back and can’t move anything but his face and one arm, and he’s gonna die on this tiny little planet. It is a sad-sack end to his sad-sack life. He’s such an insignificant criminal that the cops aren’t even going to look for him.

He’s gonna die and he’s actually at peace with it.

The planet is not lifeless, and there is a tiny annoying bug that starts bothering him, and then it starts bothering him in his mind, like psychic, man.

“I am Yirn, one of the People,” the soft thought informed him. “I am not what a bug is. Tell me, wonderment, how can something so huge be alive?”

So Pearson told him. He told the bug his name, and about mankind, and about his sick, sad existence that was soon to come to an end, and about his paralysis.

Yirn is from a poor tribe, one pushed into the wasteland. Pearson began to help as best he can. The daily rains manage to keep him hydrated, and the People manage to feed him. He guides them to the concentrated food packets of his spacesuit. Better yet, he grabbed a ham sandwich with tomatoes on it, and a carrot or two before swiping that gimpy ship, and from these he starts to teach the People agriculture, and with the energy from the concentrates they have the energy to do it.

And from there, over the short generations of the People that Pearson helps them build a planetary civilization. When humans finally get to the tiny planet they discover a very advanced society whose greatest engineering feat is a giant grave for Pearson.

Alan Dean Foster’s career needs little discussion. He was one of the only writers in this issue whose name I recognized.

Asimov’s 1979 is 192 pages and I have got to wrap this up! So I’m skipping the letters section, and will leave the final world to Dr. Asimov, in response to a particularly salty letter.

If you think a story is imperfect, consider it a challenge. Do better, and let us see it.

Previous entries the Quatro-Decadal Reviews include:

1969

Amazing Stories, November 1969

Galaxy Science Fiction, November 1969

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, November 1969

Worlds of If, November 1969

Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact, November 1969

Venture Science Fiction, November 1969

A Decadal Review of Science Fiction from November 1969: Wrap-up

1979

Quatro-Decadal Review, November 1979: A Brief Look Back

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, November 1979

Galileo, November 1979

Analog, November 1979

Adrian Simmons is an editor for Heroic Fantasy Quarterly, support them on Patreon!

I grew up in a small town in Manitoba, Canada, the town had a population of 1800, and the only place I could buy new SF was the local co-op drugstore, so the On Books always allowed me to dream of what books I could buy when I got to the “big city” of Yorkton (population 15,000) or Brandon (population 36,000). I made extensive lists for my town library to see of they could transfer them in as well.

So, IASFM, which my grandmother bought me a subscription for as a birthday present (for five years!) was a lifesaver.

Thanks for the memory.