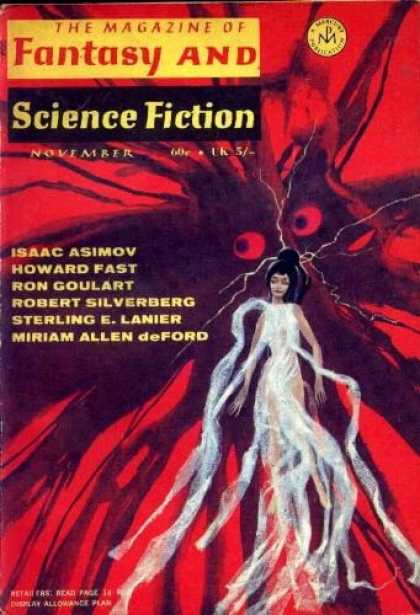

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, November 1969: A Retro-Review

This is Part 3 of a Decadal Review of vintage science fiction magazines published in November 1969. The articles are:

Amazing Stories, November 1969

Galaxy Science Fiction, November 1969

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, November 1969

Worlds of If, November 1969

Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact, November 1969

General feeling is that MoF&SF is a little flimsier than others, a bit more ‘pulpy’ (as in the paper itself, not the style) and not nearly as much artwork.

It jumps right into the fiction, “The Mouse,” by Howard Fast. Tiny aliens from a heavy gravity world come to explore Earth. Part of their exploration plan is that they find a local lifeform and augment it to be, roughly, human intelligence. In this case, the lifeform is a small mouse. It gets intelligence, and an ability to read minds. It does not take it long to figure out that the aliens don’t really have a post-exploration plan for the mouse — can’t come back to their homeworld due to the gravity, and they didn’t bother making any other intelligent mice, so they tearfully abandon it to commit suicide. A fairly gripping ending to a fairly poor set-up.

“A Feminine Jurisdiction” by Sterling E. Lanier. This is one of the continuing adventures of Brigadier Donald Ffellowes. The story unfolds at a leisurely pace — with the boys down at the pub taking about the dames and then D. Ffellowes discussing one of his wartime adventures, beginning with the set-up and intrigue around Greece, and leading to a shipwreck on a small uncharted island and being harassed by a downed German pilot. It isn’t a great story, but it isn’t bad, either. Lanier deserves a bit of credit for going past the obvious Medusa idea and going into the other gorgons. He also adds a bit of a Lovecraftian touch to things. I’m not super-familiar with the gorgons, so I have a feeling that I was missing some things.

“Penny Dreadful,” by Ron Goulart, Writers writing about writers is always a tricky proposition, and although Goulart doesn’t completely botch it, he also doesn’t completely pull it off. Hard-hitting writer and man-of action Joe Silvera mostly seems to do work, get stiffed, and then beat the payment out of people. The story actually starts with him muscling some dough from a guy, and from there he gets hired to do some ghost-writing on the Wolfpit Spanner stories. The real writer is making a political run and wants the Spanner to be a back-up. Thing is, Wolfpit Spanner is a real person and Silvera has to spend some time around him getting the scoop. Then there are the Bugs’ political opponents, who are trying to whack him and Silvera has to keep thwarting them so that Bugs can pay him, which, of course, he doesn’t do.

Book Review Column by Alexi Panshin. Panshin has concerns, major concerns, of just where science fiction is at.

Until recently, to be presented as science fiction meant small risk of failure and an absolute limitation on success. We have spent forty years as a self-sufficient, self-supported and generally ignored magazine literature.

Goes on to note that Stranger in a Strange Land and Dune have been ‘vogue’ items, and actual good movies (2001, Charlie, Rosemary’s Baby) have been made. Movies and TV are going up, yet the magazines seem to be going down. He has worries that good SF writers will dilute their works for mass appeal, and that non-sf writers will window-dress their works to try to cash in on SF’s increasing popularity. The books he reviews are “interesting examples of the curious, uncertain and half-formed state of the field of science fiction.”

|

|

|

Andromeda Strain, by Michael Crichton — a pan! “It has been favorably reviewed by Life, Look, and the New York Times, and it has sold to the movies for an impressive sum. It is also cheap, sensationalistic, hastily written trash […]” He unloads for like, three more pages.

The Lion of Comarre and Against the Fall of Night, by Arthur C. Clark — fails the sniff test! “The stories are dated by an uncritical scientism — again not much different from Crichton and his Indexes of Effectiveness, though infinitely more honest — by cans, by the advent of transistor radios, and by hast and shortcuts.”

A Spector is Haunting Texas, by Fritz Lieber — also disliked.

The Left Hand of Darkness, by Ursula K. LeGuin — not a fan. “The Left Hand of Darkness is well above the average in literacy, invention and ambition […] but ultimately as a story it is a flat failure.”

…I don’t begrudge anyone their opinion, and there is something refreshing about reading what people really thought of works before they were, you know, works, but swing and miss, there, Panshin!

“The Crib Circuit,” by Mariam Allen DeFord

A woman cryogenically frozen in the 1970s is woken up, her cancer cured in the 25th century. Problem is, there is an optimum population ow and she is literally one too many, so after they finish studying her, getting her take on history and such, she will be painlessly euthanized. There is a bit of a gap in their understanding of history, and desperate times call for desperate measures!

“Wait!” cried Alexandra suddenly. She felt a little light-headed; there was every possibility that in a few minutes she might be cut short and ordered liquidated as mentally unsound. But it was now or never.

She braced herself.

“Before you start,” she said, “tell me one thing: do you want the official history, or the real history?”

“You mean not the same?”

“Of course not. […] Those in power often lied to the public, because they feared that if they told the truth, the result might be panic, perhaps total chaos if it couldn’t be stopped in time.”

She essentially presents herself as a physic super-spy intentionally put into cryogenic freeze as a safeguard against certain hostile alien forces gaining power over the long-term. It is a very clever twist, and works quite well. But the ending doesn’t work well at all, it seemed a bit tacked-on, like DeFord didn’t know what to do with the story, or someone asked her to change/tighten it.

“Come Up and See Me Sometime,” by Gilbert Thomas.

It doesn’t pay to have an exceptional child. They’re always doing things you can’t understand.

I touched the machine and it moved gently with my hand, effortlessly, but it always came back to its original position — tipping slightly.

The room was circled with photographs, blow-ups of Yuri Gagarin, Gus Grissom, Roger Chaffee, Ed White, all the new heroes, with his worktable covered with electronics and books I couldn’t figure out. He was only 12 and now he was hovering in his spacecraft six feet off the floor […]

The main character (MC) has problems, man. He is cursed with an exceptional child and a dead wife. Clearly this is a very melancholy story. Ted, the MC’s son, has built a spaceship, and is inside and won’t come out. The MC tries talking to him to get him out, but more, he tries to connect with him somehow. There are posters all over the room, space-stuff, but also some weird pseudo-science, and Thomas breaks the action with quotes and descriptions of the posters, which serves as a bizarre Greek chorus to a growing tragedy. Because it’s hard to connect to your too-bright son when he starts playing back all the fights that you’ve had with his mother before she killed herself. The kid eventually comes out of the ship, but only because ships are, like his little tape recorder, just to get his dad talking — the exceptional child doesn’t actually need the ship to travel to distant worlds.

“After the Bomb Clichés,” by Bruce McAllister. The story delivers exactly what is in the title. Martin Potsubay, computer analyst and sick-in-the-mud, buys a bomb shelter because he’s figured out that a nuclear war is going to happen. And, well, it happens, and then all the clichés of jerk-stuck-by-himself-in-a-bomb-shelter play out, and then the but-it-really-wasn’t-a-nuclear-war-at-all clichés play out because it was the biblical Armageddon and all the clichés that implies.

Article, The Sin of the Scientist, by Isaac Asimov. Mr.* Asimov analyses Robert Oppenheimer’s remark that “Physicists have known sin” and just how “sin” would be relatable to the scientific endeavor. As is often the case, Asimov’s non-fiction writing is quite good.

There is a strong and growing element among the population which not only finds scientists suspect, but is finding evil in science in the abstract.

It is the whole concept of science which (to many) seems to have made the world a horror. The advance of medicine has given us a dangerous population growth; the advance of technology has given us a growing pollution danger; a group of ivory-tower, head-in-the-clouds physicists have given us the the nuclear bomb; and so on and so on and so on.

His conclusion? The chlorine gas attacks at Ypres on April 22, 1915 in WWI is the definition of a scientific sin. The chlorine gas, and the strategy to use it, was created by one Fritz Haber.

To what constructive use can nerve gas in ton-lot quantities or plague bacilli in endless rows of flasks be put?

“Diaspora,” by Robin Scott. Earth, doomed, sends its best and brightest to the planet Eleuthera to start again. The best and brightest, and for some odd reason, Angelo DeFillipo, a Pittsburg tavern owner. DiFillipo has problems, his son is in that awkward stage between being a boy and a man, and he has the enmity of most of the command crew, and he’s chafing against the stultifying rules of the colony, and especially the colony’s leader, the fire-and-brimstone Captain Angleton. Finally he can’t stands no more!

DiFillipo had long since gathered up and carried off to the cache site nearly everything he could think of they would need, but he loaded Tommy and himself with anything in the warehouse that took his fancy: a spare pair of pliers, a dozen packages of needles, a small transceiver and a spare batter pack, a five-pound box of sixteen-penny nails, a pair of welder’s goggles. It was useless stuff, perhaps, but he didn’t know when he might have another chance to take a crack at an unguarded warehouse.

His break made, they set up at a reasonably secure place well away from the colony, The Man pursues, but is unwilling to shoot it out. Years pass, some others defect to join him, then Angleton captures him in the middle of the night.

The big reveal, and a frequent big reveal of this kind of ‘Stagnation of the race!’ stories is that the whole thing is often a setup, with The Man just looking for someone ballsy enough to take the next step (see my review of Mack Raynold’s The Cosmic Eye).

In a lot of ways what saves the story is Angleton’s reveal of the burden he’s borne for 16 years waiting for DiFillipo to man-up.

Someone who could act and speak and live the role of everyone’s idea of the Commander: el Caudillo, the President, der Führer, Comrade Chairman, the Pope, the Maharishi, il Duce, le Roi, the Chairman of the Board, all rolled into one. But no one who is really sane makes a really great leader, and no one who was really insane could be entrusted with so much power. No one but an actor could appear to be all that and remain sane.” Angleton chuckled wryly. “And on that latter point, I don’t know that I’ve always succeeded. Power corrupts in many ways. Even borrowed, secondhand power…

The other thing that saves the story is that the colony is really prepared for the worst. Among the lies that Angleton has lived is that the colony didn’t come with 20 years of supplies, but over a century — so much that complacency would be a real threat.

But then, the story kind of closes with a weird vibe, with DiFillipo deciding to dick over/haze his son just like Angleton has dicked over/hazed him.

“After the Myths Went Home,” by Rover Silverberg. Sometime in the far future, 12,400 AD or so, they build machines — not time machines necessarily, but machines that can create people from the past. An upgrade to the machines during the unnamed narrator’s tenure as Curator of the Hall of Man allows them to approximate gods. Then to approximate heroes, then the gods of sciences. The paint comes off pretty quickly:

They wanted us to love them. They asked questions — some of them, anyway — that pried into the inner workings of our world, and embarrassed us, for we scarcely knew the answers. They grew vicious, and schemed against each other, sometimes causing perils for us.

Leor had provided us with a splendid diversion. But we all agreed it was time for the myths to go home. We had had them with us for fifty years, and that was quite enough.

The last one sent back is Casandra, who asks “Who will comfort your souls during the dark times ahead?” Which is pretty much what you’d expect her to say. Sometime later the aliens invade and enslave us all and we have nobody to pray to. It is well written but the ending was almost a mirror of “Crib Circuit.”

*That’s Dr. Asimov, if you’re nasty.

There are several things that become apparent on this, the third of the November 1969 SF magazine reviews. What really stands out is the kind of… closed loop of sci-fi writing. Goulart is in both Galaxy, 11, ’69, and MoF&SF, as is Robert Silverberg. Alex Panshin writes a book review column for MoF&SF and has story in Amazing 11, ’69. There are other parallels in Worlds of If, which is my next review.

Adrian Simmons is an editor for Heroic Fantasy Quarterly. His last review for us was the July/August 2017 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

I’m trying to get hold on interlibrary loan of a Ffellowes collection that contains that story.

The reviews of the sf magazines, notably Fantastic and F&SF, from the 1960s are among my favorite features here at Black Gate. These magazines were among the few venues for new fantasy fiction back then.

That F&SF cover art was by Gaughan, surely — ? I think we overlook the fact, or forget it, that, at the time, Jack Gaughan was one of the principal or even THE principal artists for fantasy paperbacks and magazine art. Frazetta, the Dillons, Jones, and (towards the end of the 1960s) Bob Pepper and Gervasio Gallardo, may loom in our memories. But it was Jack Gaughan who did the cover art for the first paperbacks of The lord of the Rings (the Ace ones); jG who painted the cover for Ace’s edition of Alan Garner’s The Weirdstone of Brisingamen; the Ace paperback of Myers’ Silverlock, if I’m not mistaken — to name some that come to mind right away — and so many F&SF covers….

Major Wootton- Ah! You’re right, I didn’t credit the cover… I don’t have the magazine with me now, but I’ll check on it when I can.

I’ve got two more 1969 magazine reviews to do (three if I delve into “Venture” Magazine– which I saw advertised in “Worlds of If”), then I move on to 1979.

Without checking, I’m virtually sure that Gaughan also painted the covers for a couple of Moorcock’s Elric books (might be the art was better than the stories!), for Lancer. Then there were all those Andre Norton books that were at least borderline fantasy for which Gaughan did the art. Take Worlds of Fantasy, the short-lived fantasy pulp. It was Gaughan who did the cover art for the issue featuring Le Guin’s middle Earthsea book The Tombs of Atuan (and the interior drawings). Again, these are things that come to mind without hunting around. He really was one of the major fantasy artists in American publishing in the 1960s, both because his work was good and because there was so much of it. Your column here prompted me to realize that!

And yes, that F&SF cover is by Gaughan.

Major Wooton- like I said in the review, there really isn’t any other artwork in the issue, except for a rather disturbing cartoon. Amazing Stories and Galaxy both had internal artwork. As this is the only MoF&SF that I’ve read from that time, I’m not sure if that was their standard practice.