Vintage Treasures: The Best of Fredric Brown

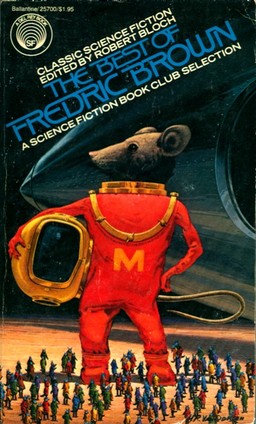

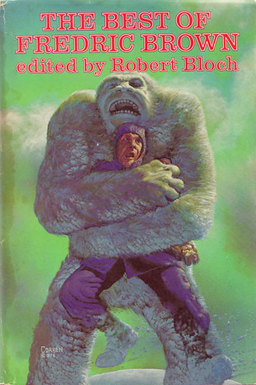

Welcome to the 13th installment of my ongoing examination of one of the most influential book series of my youth, Lester Del Rey’s Classics of Science Fiction line. This time, we’re looking at the 1977 release, The Best of Fredric Brown, edited by Robert Bloch (who had his own entry in the series eleven months after this one, which I discussed back in July.)

Welcome to the 13th installment of my ongoing examination of one of the most influential book series of my youth, Lester Del Rey’s Classics of Science Fiction line. This time, we’re looking at the 1977 release, The Best of Fredric Brown, edited by Robert Bloch (who had his own entry in the series eleven months after this one, which I discussed back in July.)

The Classics of Science Fiction line was my introduction to many of the major SF and fantasy writers of the 20th Century (well, that and The Hugo Winners, which first introduced me to Poul Anderson, Walter C. Miller, Arthur C. Clarke, and others, and of course the various volumes of The Science Fiction Hall of Fame).

All that education didn’t teach me much about Fredric Brown, however. A week ago, I probably could have named only one Fredric Brown short story from memory, “Arena” — which, admittedly, I dearly loved. I first read it in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One, where it was selected as one of the finest short stories ever written, but even before that, I knew it as the Star Trek episode of the same name.

You probably think of it as, “Isn’t that the one where Kirk throws styrofoam rocks at the Gorn?”

Yes. Yes it is. And even though it has been much-parodied (including a brilliant video game commercial starring an 80-year old William Shatner and an aged Gorn in a re-match), it’s still one of the finest episodes of the original series.

So before I sat down to assemble my notes for this article, I took my paperback copy of The Best of Fredric Brown with me on a business trip, to a banking show in Las Vegas, and used the opportunity to reacquaint myself with the author. Honestly, I wasn’t expecting all that much. Not every installment in the Classics of Science Fiction could be a winner.

My mistake.

The Best of Fredric Brown is one of the best short story collections I’ve read in years. Brown is frequently compared to O. Henry for his gift for twist endings and the comparison is apt. Even when you’re on the alert, Brown manages to constantly surprise and delight you in a way that very few authors — in the genre or out — can pull off.

[Click on any image in this article for a bigger version.]

Fredric Brown was born on October 29, 1906 in Cincinnati. He was a proofreader for the Milwaukee Journal, writing pulp fiction on the side, primarily for the detective, mystery, fantasy, and science fiction pulps.

Fredric Brown was born on October 29, 1906 in Cincinnati. He was a proofreader for the Milwaukee Journal, writing pulp fiction on the side, primarily for the detective, mystery, fantasy, and science fiction pulps.

In his introduction, Bloch relates the circumstances that changed Brown’s life and eventually led to his career as a full-time writer:

One day he called me all aglow; he’d just received a phone call from a prominent editorial figure in New York who headed up one of the leading pulp-magazine chains. Would Fred consider taking over a portion of the editing assignment for seventy-five hundred a year?…

It was far more than Fred was earning , or hoped to earn, at his newspaper job — and if he could augment the sum by writing novels on the side, it would exceed his wildest expectations. Fred… quit his job and went to New York, where he learned there had been a slight misunderstanding during his telephone conversation.

The stipend quoted by the editorial director had not been seventy-five hundred a year; it was seventy-five dollars a week.

A dark cloud settled over Fred’s life.

Fortunately, other changes were in the works as well, and that “dark cloud” didn’t rain on Brown for long. As Bloch relates:

In a few short years, the imposing chain of pulp magazines he’d hoped to head up had disappeared forever. And in their place was a mushrooming market of paperbacks, competing for the privilege of reprinting hardcover mysteries and science fiction. Foreign editions began to command more-respectable earnings, television was purchasing stories for adaption, and the new men’s magazines, led by Playboy, paid higher and higher rates for short stories.

Through fortuitous circumstances, Fredric Brown found himself in the right place at the right time. Critically, commercially, and above all creatively, he was a success.

It was during this period that Brown produced a string of highly regarded and commercially successful mystery and detective novels.

It was during this period that Brown produced a string of highly regarded and commercially successful mystery and detective novels.

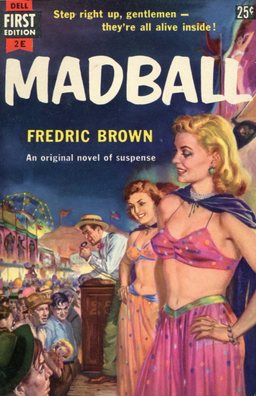

Ultimately, he published over two dozen, including The Fabulous Clipjoint (1947), which won the Edgar Award for outstanding first mystery novel, The Dead Ringer (1948), The Screaming Mimi (1949) — filmed in 1958 as an Anita Ekberg and Gypsy Rose Lee picture, directed by Gerd Oswald — Night of the Jabberwock (1950), The Far Cry (1951), Madball (1953), and The Wench Is Dead (1955).

But it’s his SF and fantasy work that is best remembered today.

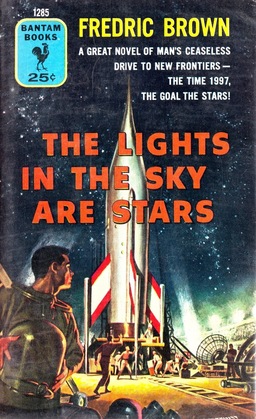

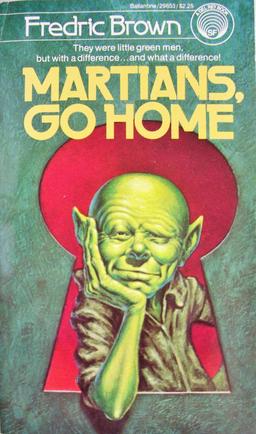

That’s somewhat surprising, considering that he was much more prolific as a mystery and detective writer. In fact, while he penned dozens of novels in those genres, he wrote only five SF novels in his long career: What Mad Universe (1949), The Lights in the Sky Are Stars (1953), Martians, Go Home (1955), Rogue in Space (1957), and The Mind Thing (1961).

What Mad Universe is still considered a classic, even if it is rather dated. It follows the adventures of Keith Winton, editor for a prominent science fiction magazine, who is thrown into a strange parallel dimension when an experimental rocket crash-lands on his friend’s home.

Here many of the conventions of pulp SF are brought dazzlingly to life — including scantily-clad pin-up girls who turn out to be astronauts, aliens, and more. In their Recommended Reading column in the February 1950 F&SF magazine, editors Boucher and McComas cited What Mad Universe as the best SF novel of 1949.

Martians, Go Home may be Brown’s most famous novel, and not as a result of the 1990 Randy Quaid movie version. Originally published in the September 1954 issue of Astounding, it exhibits much of the humor that made What Mad Universe a classic.

Set in the distant future of 1964, the story opens with Luke Deveraux, a 37-year-old SF writer, who has secluded himself away in a desert cabin to finally finish his novel. Deveraux opens his door in a drunken stupor one night to find a little green man, a Martian, a one-creature invasion who proceeds to make Deveraux’s life hell.

As you can probably tell from the description (and Frank Kelly Freas’s famous cover, right), Martians Go Home isn’t a serious novel. At least, it’s not serious very often.

As you can probably tell from the description (and Frank Kelly Freas’s famous cover, right), Martians Go Home isn’t a serious novel. At least, it’s not serious very often.

Richard A. Lupoff called the book “one of the most charming bits of SF-whimsy ever written,” and that description is still apt.

The Lights in the Sky Are Stars is an uncomfortably prophetic novel, especially today. Written when the space program was brand new — and some 16 years before the first moon landing — it imagines a future where it is no longer in the public spotlight the way it was and Congress has cut off funds, starving the space program in favor of domestic initiatives. It follows an aging astronaut who takes matters into his own hands in an attempt to get his beloved space program back on track.

All five novels are collected in a single handsome edition from NESFA Press, under the title Martians and Madness: The Complete SF Novels of Fredric Brown (640 pages, 2002).

To be honest, while his SF has received more attention than his mystery, Brown isn’t particularly remembered today for his SF novels, either. Other than the omnibus edition, none of them are in print — and most haven’t been in print for decades.

No, today Fredric Brown is chiefly remembered as the author of a number of truly masterful SF and fantasy short stories, collected during a lengthy career in half-a-dozen highly regarded volumes.

Here’s Robert Bloch again, from his introduction to The Best of Fredric Brown:

For a time Fred tried his hand at films and television… And, Hollywood being what it was — and, alas, is — it was only natural that his efforts met with little acceptance. Producers didn’t understand Fred…

Again, he reverted to print. And Hollywood’s undoubted loss was our gain, for he continued to turn out a series of unique, highly individualistic tales: stories which established him in the genre. If he’d never written anything except “Puppet Show,” we’d have reason to be grateful for Fredric Brown’s contribution to science fiction, but there were many others…

And it is in his stories that Fred’s fame endures.

Indeed. While Brown left behind a rich body of work, his real fame rests in a handful of his short stories, which include among them some of the best SF ever written.

Indeed. While Brown left behind a rich body of work, his real fame rests in a handful of his short stories, which include among them some of the best SF ever written.

In fact, if he’d written nothing else, he’d still be remembered for his fabulous story “Arena,” originally published in Astounding Science Fiction, June 1944.

“Arena” is the tale of Bob Carson, an advance scout of the largest human armada ever created, who is outside the orbit of Pluto when he encounters a leading scout of a massive fleet of alien invaders. Carson pursues the invader until they both suddenly encounter a strange planet, where no planet should be. Blacking out after attempting emergency evasive maneuvers, Carson awakens naked on hot sand, not far from a hideous red alien whom he soon discovers is the pilot of the other scout craft.

Carson and the alien have been selected by an alien superintelligence to conduct a proxy battle for the upcoming clash of armadas. The superintelligence, in a patient telepathic link, explains to both champions that the upcoming war will so deeply scar both races that neither will survive.

It has chosen this method, it explains, to determine which race is worthy of survival. The winner will be transported back to his ship. The loser will die — along with his entire race.

“Arena” is a tightly-constructed adventure with all the hallmarks of the finest pulp science fiction: fast action, high stakes, bug-eyed monsters, and an inventive and resourceful hero.

It also has a terrific setting — a strange alien desert, peopled by semi-telepathic lizards, and odd plants — and more than a few surprises for the reader.

Several stories have been told about just how this famous tale ended up as one of the most famous scripts for the most acclaimed SF show in history. In their seminal book, Inside Star Trek, the show’s producers Herbert F. Solow and Robert H. Justman give the inside story on how it happened.

Herb: Plain and simple, we were running out of scripts. Several writers hadn’t delivered as promised, and suddenly, there were only two choices of action available to us: either shut down the shooting company or somehow find another script. Gene Roddenberry was away and Gene Coon was busy rewriting other writers’ scripts, but none of those would be ready in time. So Coon decided to take some direct action. He asked Bob if he could leave the studio a little earlier that Friday to go home, lock himself in a room, and not emerge until Monday morning with a new script…

So just before 6:00 Friday, Coon drove his Toyota Land Cruiser off the lot and did not return until midmorning Monday — with a new script in hand. Now, I was thrilled, The script was quickly put into mimeo and copies were rushed to NBC for network approval and Kellam DeForest’s office for factual research and legal approvals.

But suddenly, the thrill was gone. Coon, an ardent reader of science fiction since he was a child, in his haste to create a story, had inadvertently based part of his script on a short story that had been written by Fredric Brown. Kellam’s assistant Joan Pierce, who reviewed, analyzed, and wrote the research reports on all Star Trek scripts, recognized the story. She remembers that when she advised Coon of the problem, his reaction was a horrified “Oh my God!” Joan has absolutely no doubt he was unaware he had “lifted” the material…

Gene Coon and I met with Bernie Weitzman and Ed Perlstein and formulated a plan. Business Affairs would call Brown, tell him Star Trek would like to buy his story, and offer a fair price. Brown was thrilled to have one of his stories on Star Trek and accepted the deal. We never did tell him that the script had already been written.

While Gene L. Coon’s “Arena” script clearly stole its core plot from Fredric Brown’s short story, I also think it’s a superior tale, as Kirk’s mercy towards the Gorn at the end adds a profound element of hope, creating a fine counterpoint to Brown’s original theme of human physical and mental superiority.

While Gene L. Coon’s “Arena” script clearly stole its core plot from Fredric Brown’s short story, I also think it’s a superior tale, as Kirk’s mercy towards the Gorn at the end adds a profound element of hope, creating a fine counterpoint to Brown’s original theme of human physical and mental superiority.

Coon’s script is special for other reasons as well. Although the existence of Starfleet had been established in previous episodes, it wasn’t until “Arena” that Star Trek established the existence of the United Federation of Planets. One of the most enduring elements of the modern SF canon, created during a hurried all-nighter by Gene L. Coon. Why does that make so much sense?

Ironically enough, by the time I came across Fredric Brown’s “Arena,” it was the third version of the iconic story I’d encountered.

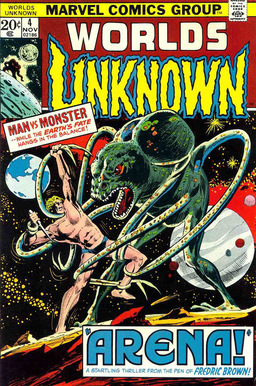

The second was Gerry Conway’s marvelous adaptation for the fourth issue of Marvel Comics World Unknown, a short-lived magazine that retold classic SF short stories. World Unknown lasted only eight issues, from May 1973 to August 1974, but it is still missed today.

You can read the entire story, as scripted by Gerry Conway, penciled by John Buscema, and inked by Dick Giordano, at Diversions of the Groovy Kind. The Internet is good to you.

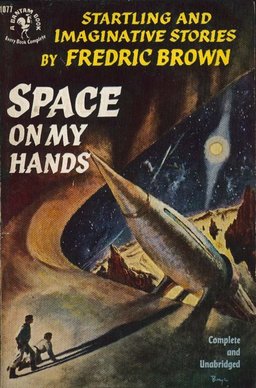

Fredric Brown’s short science fiction and fantasy was collected in several major volumes, starting with Space on My Hands (1951), Angels and Spaceships (1954), Honeymoon in Hell (1958), Nightmares and Geezenstacks (1961), Daymares (1968), Paradox Lost, and Twelve Other Great Science Fiction Stories (1973), The Best Short Stories of Fredric Brown (1982), and And the Gods Laughed (1987).

All are out of print. Fortunately for you, the irreplaceable NESFA press collected all of Brown’s short science fiction in one monumental 693-page volume: From These Ashes: The Complete Short SF of Fredric Brown, released in hardcover in 2001 and still in print (ably reviewed for Black Gate by James Enge here).

If you’re interested in Brown’s crime fiction, I also highly recommend Miss Darkness: The Great Short Crime Fiction of Fredric Brown, a 740-page paperback omnibus from Bruin Books, published just last year.

And you’re in luck: the diligent Stephen Haffner at Haffner Press has announced that he’s turning his attention to Fredric Brown next, with a series of deluxe hardcovers collecting his complete work. The first volumes of The Collected Fredric Brown, Murder Draws a Crowd, gathering humorous short tales from vintage trade journals like Excavating Engineer, and Death in the Dark, gathering his contributions to detective & mystery pulps of the late 30s through the end of 1942, are already on the schedule.

But if you’re interested in a representative sample of Brown’s many gifts as an SF and fantasy writer, I highly recommend the book at hand: The Best of Fredric Brown, a fabulous collection that includes virtually all of his most famous tales.

But if you’re interested in a representative sample of Brown’s many gifts as an SF and fantasy writer, I highly recommend the book at hand: The Best of Fredric Brown, a fabulous collection that includes virtually all of his most famous tales.

That includes “Arena,” as well as “Nightmare in Yellow,” a two-page wonder featuring an ingenious embezzler who’s planned the perfect crime, and who decides to kill his wife just before he executes he perfect getaway on his fortieth birthday. And who’s standing in the dark doorway after striking the lethal blow, his dead wife in his arms… (spoiler alert!) as the lights suddenly come on and all his friends and neighbors yell “Surprise!”

Okay, that’s the only spoiler. I promise.

I think that’s Brown’s real gift. One of them, anyway. All his stories are the perfect length and his twist endings fit them precisely. Admit it — that would probably drive you crazy if it were the ending of a 30-page novella, but it’s an ideal twist for a 2-page crime story.

There’s a far more powerful twist in the last line of “The Geezenstacks.” The Geezenstacks is the name young Aubrey gives to the strange dolls her uncle Richard brings her one day. There are four of them: two men, a woman, and a little girl. A perfect match for her extended family: her father Sam, her mother Edith, and Richard.

All seems well until Sam begins to notice a series of strange coincidences. Everything that happens to the dolls while Aubrey plays with them happens to his family, too.

Sam doesn’t know what to do. Richard and Edith notice Sam’s growing obsession with the dolls, however, and decide to secretly get rid of them. Their scheme unfolds perfectly, and everything reverts to normal… for a short time.

Until that killer final line.

You may think “Nightmare in Yellow” is as short as a Fredric Brown story gets. But you’d be sadly underestimating Brown’s ability to pack a wallop in well under 300 words. That’s the case in “Answer,” a one-page, far-future tale in which an exalted potentate makes the final connections that links every computer in the galaxy.

Dwar Ev threw the switch. There was a mighty hum, the surge of power from ninety-six billion planets. Lights flashed and quieted along the miles-long panel.

Dwar Ev stepped back and drew a deep breath. “The honor of asking the first question belongs to you, Dwar Reyn.”

“Thank you,” said Dwar Reyn. “It shall be a question which no single cybernetic machine has been able to answer.”

He turned to face the machine. “Is there a God?”

If you’re like me, you remember the answer to Dwar Reyn’s question, even if you don’t truly remember the story. Maybe you read it ages ago, and simply forgot who wrote it. Or just as likely, the story was told to you by a fellow fan, the way the best stories have always been shared: Passed back and forth until they’re part of our collective unconscious.

If you’re like me, you remember the answer to Dwar Reyn’s question, even if you don’t truly remember the story. Maybe you read it ages ago, and simply forgot who wrote it. Or just as likely, the story was told to you by a fellow fan, the way the best stories have always been shared: Passed back and forth until they’re part of our collective unconscious.

Whatever the case, I bet you’ll still feel that same chill when you read the final line one more time.

Robert Bloch says “If he’d never written anything except “Puppet Show,” we’d have reason to be grateful for Fredric Brown’s contribution,” and I have absolutely no doubt he is correct. As much as I admire “Arena” and “The Geezenstacks,” I think “Puppet Show” puts them both in the shade, in terms of its sheer inventiveness, narrative power, and — especially — its humanity.

The story opens with the line:

Horror came to Cherrybell at a little after noon on a blistering hot day in August.

The horror in question is mounted on a burro led by a grizzled old prospector. It is some nine feet tall, with raw red skin that looks as if it has been skinned alive. When it reaches Cherrybell, it plops down in the sand, saying only “High gravity planet… can’t stand long.”

It doesn’t take long before representatives from the nearby airbase are alerted and arrive to investigate. Things happen quickly after that. Two helicopters land, a tape recorder is produced, and the burro-riding traveler reveals what the assembled crowd has long-since figured out: he is an extraterrestrial. In fact, he is here to extend an invitation to join a peaceful galactic union, a membership that will brings untold benefits to mankind.

There’s just one catch: mankind has to pass two simple tests first. Both will be administered by the exhausted, cold, and grotesque alien before them. The first is a test of xenophobia and, judging by the polite response so far from the military men and the assembled crowd, the alien is willing to award mankind a pass.

But the second test is much, much more subtle. And when the army colonel asks about it, he’s informed they’re in the middle of it now…

“Puppet Show” has more than one twist. Science fiction is filled with first contact stories, but few — if any — pack the punch of this one.

And of course, just when all the twists are revealed and you’ve finally got that story figured out, there’s that killer last line.

I can’t remember the last time I’ve had as much fun with a single collection. Obviously, not every story may suit your taste, but Brown hits the mark far more often than he misses.

Here’s the Table of Contents:

Contents

Introduction: A Brown Study, by Robert Bloch

“Arena” (Astounding Science Fiction, June 1944)

“Imagine” (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, May 1955)

“It Didn’t Happen” (Playboy, October 1963)

“Recessional” (Dude, March 1960)

“Eine Kleine Nachtmusik” (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, June 1965) by Fredric Brown and Carl Onspaugh

“Puppet Show” (Playboy, November 1962)

“Nightmare in Yellow” (Dude, May 1961)

“Earthmen Bearing Gifts” (Galaxy, June 1960)

“Jaycee” (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, 1955)

“Pi in the Sky” (Thrilling Wonder Stories, Winter 1945)

“Answer” (Angels and Spaceships, 1954)

“The Geezenstacks” (Weird Tales, September 1943)

“Hall of Mirrors” (Galaxy, December 1953)

“Knock” (Thrilling Wonder Stories, December 1948)

“Rebound” (Nightmares and Geezenstacks, 1961)

“Star Mouse” (Planet Stories, February 1942)

“Abominable” (Dude, March 1960)

“Letter to a Phoenix” (Astounding Science Fiction, August 1949)

“Not Yet the End” (Captain Future, Winter 1941)

“Etaoin Shrdlu” (Unknown Worlds, February 1942)

“Armageddon” (Unknown, August 1941)

“Experiment” (Galaxy, February 1954)

“The Short Happy Lives of Eustace Weaver I, II, & III” (Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, 1961)

“Reconciliation” (Angels and Spaceships, 1954)

“Nothing Sirius” (Captain Future, Spring 1944)

“Pattern” (Angels and Spaceships, 1954)

“The Yehudi Principle” (Astounding Science Fiction, May 1944)

“Come and Go Mad” (Weird Tales, July 1949)

“The End” (Nightmares and Geezenstacks, 1961)

The Best of Fredric Brown was edited by Robert Bloch and first published in hardcover by the Science Fiction book club in January, 1977, with a cover by Richard Corben. The paperback edition was published by Del Rey in May 1977, with a cover by H.R. van Dongen. It is 315 pages in paperback, priced at $1.95.

You can see my last entry in this series, The Best of James Blish, here, So far, we’ve covered the following volumes in the Classics of Science Fiction line (in order of original publication):

The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum

The Best of Fritz Leiber

The Best of Henry Kuttner

The Best of John W. Campbell

The Best of C M Kornbluth

The Best of Philip K. Dick

The Best of Fredric Brown

The Best of Edmond Hamilton

The Best of Murray Leinster

The Best of Robert Bloch

The Best of Jack Williamson

The Best of Hal Clement

The Best of James Blish

The Best of John Brunner

See all of our recent Vintage Treasures here.

For more on Fredric Brown, try the io9 article “The Best Science Fiction Writer You Didn’t Know You’d Read,” Part I, and Part II.

I think Brown is one of the most consistently creative authors in any genre. He tends to be a writer’s favorite, drawing admiration from authors ranging from Ray Bradbury to Mickey Spillane.

Looking at the table of contents of this book, one story leaps out at me— the brilliant, cruel, and utterly outrageous, Come & Go Mad.

Made me think.

In addition to his almost uncanny ability to turn a sharply defined plot (again & again & again &…) Brown had both the fertile imagination and prose confidence to tell a story that held and convinced the reader, even if the story’s elements were incredible even by the standards of pulp SF.

Come & Go Mad is the kind of story that leaves the reader unable to tell anyone about it in conversation and have them understand even a glimmer of the story’s power.

In fact, if you describe the plot flatly to your companion, they will very likely roll their eyes in weary disbelief. Oh, you can’t be serious…

Weird Tales published a number of these kind of tales. Edmund Hamilton’s He Who Hath Wings, and Seabury Quinn’s Roads are both good examples.

But Come and Go Mad is a real prize— for its lunatic invention, fearless presentation and the fact that it works so very well.

> He tends to be a writer’s favorite, drawing admiration from authors ranging from Ray Bradbury to Mickey Spillane.

John,

Very true. Robert A. Heinlein dedicated Stranger in a Strange Land to Brown (and Philip Jose Farmer, and someone named Robert Cornog). I understand Spillane considered Brown his favorite writer.

Have you tried any of his mysteries?

> Weird Tales published a number of these kind of tales. Edmund Hamilton’s “He Who Hath Wings,”

> and Seabury Quinn’s Roads are both good examples.

> But Come and Go Mad is a real prize

I should have talked about “He That Hath Wings” in my Hamilton article. Ah well, nobody’s perfect.

I feel constrained by length in these articles. I should have talked about “Come and Go Mad,” and “Earthmen Bearing Gifts” and “Star Mouse,” but this post had already passed 3,800 words, which is well past the upper limit for even the most patient blog readers, I think.

Besides, I really think many of these stories deserve a post of there own. Certainly “Arena” and “Puppet Show” do. Maybe that will be my next project…

I read the SFBC edition in high school (or was it middle school?). My favorite was “Eine Kleine Nachtmusik”.

He was one of the most inventive and imaginative authors in the history of the field. I know he’s well respected by writers such as Lawrence block for his mystery writing, even if the average mystery reader these days doesn’t know who he is. I would have sworn “Answer” was an Asimov story, but it has stayed with me through the years.

Keith,

Agreed — I thought “Answer” was an Asimov story, although I suppose I was just getting it mixed up with Asimov’s “The Last Question” (in which the ultimate’s computer’s final pronouncement is “Let there be light.”)

John,

Yep, that was the Asimov story I was thinking about.

“Star Mouse” always leaves me a little sad.

Fletcher,

It was a peculiar choice for the cover story, don’t you think?

[…] fact, just last week I examined The Best of Fredric Brown, calling it “one of the best short story collections I’ve read in […]

[…] Vintage Treasures: The Best of Fredric Brown […]

[…] brought a battered paperback with me on a flight back from Las Vegas last November. A week later I wrote about it, […]

[…] of Henry Kuttner The Best of John W. Campbell The Best of C M Kornbluth The Best of Philip K. Dick The Best of Fredric Brown The Best of Edmond Hamilton The Best of Murray Leinster The Best of Robert Bloch The Best of Jack […]

[…] Vintage Treasures: The Best of Fredric Brown (2013) […]

I finally finished this book. I can see why you have such a fondness for Brown; he definitely is a good writer with some very witty ideas. He’s very good at humor, and suspense, as well as surprise.

However, since I had never read Brown before, and we live in a post-M. Night Shyamalan world, a lot of his endings seemed like cheap twists or gotchas to me. Nevertheless, his stories are well worth the read.

The last story in this book was something of a surprise, “Come and Go Mad.” I found this story really disturbing. I’ve never read a story of madness from a first person perspective while also making me feel truly anxious–very effective!

[…] Black Gate — “While Brown left behind a rich body of work, his real fame rests in a handful of his short stories, which include among them some of the best SF ever written. In fact, if he’d written nothing else, he’d still be remembered for his fabulous story ‘Arena,’ originally published in Astounding Science Fiction, June 1944.” […]

[…] a few years ago here at Black Gate. Our own esteemed editor John O’Neill was reminiscing about this very book. As with so many of John’s Del Rey “Best of” posts, I was intrigued and tracked down a copy. […]