Vintage Treasures: The Best of Hal Clement

Hal Clement was perhaps the least well-known subject in the Classics of Science Ficiton series, even in 1979, when The Best of Hal Clement appeared. He’s virtually forgotten today, 10 years after he died.

Hal Clement was perhaps the least well-known subject in the Classics of Science Ficiton series, even in 1979, when The Best of Hal Clement appeared. He’s virtually forgotten today, 10 years after he died.

Ironically, he was probably the author I was personally most familiar with. Not because I read much of his fiction (not a lot was in print by the late 70s), but because of Maplecon.

Maplecon was the small local science fiction convention in Ottawa, Canada. I started attending in 1978, riding the bus downtown to the Chateau Laurier, a pretty daring solo outing at the age of fourteen. Hal Clement lived just a few hours away from Ottawa, in upstate New York, and he’d been a Guest of Honor at one of the earliest Maplecons; after that, he became a regular attendee. The convention staff referred to him warmly as “our good luck charm.”

I remember Clement — whose real name was Harry Clement Stubbs — as a friendly, highly articulate, and good-humored man. He was in his early 50s when I first saw him, so of course I considered him infinitely old. He was also soft-spoken and not prone to talking up his own work, which probably explains why all those times I heard him speak didn’t result in a lingering interest in his novels.

Clement wrote in a category that is nearly extinct today: true hard science fiction, in which The Problem — the scientific mystery or engineering puzzle at the heart of the tale — is the central character, and the flesh-and-blood characters that inhabit the story are there chiefly to solve The Problem. When Clement talked about writing, he mostly talked about the requirement to keep his stories as scientifically accurate as possible; he described the essential role of science fiction readers as “finding as many as possible of the author’s statements or implications which conflict with the facts as science currently understands them.”

Okay, that ain’t how I view my role as a reader — and I read a fair amount of hard SF. But your mileage may vary.

I read one Hal Clement novel: Half-Life. Don’t trouble yourself to find it; it’s been out of print almost since it appeared and it’s not one of his finer efforts. Here’s what I said in my SF Site review back in 1999.

This is a hard science fiction novel, and an unapologetic one at that. Fairly advanced knowledge of bio-chemistry and engineering are required to completely follow much of the casual dialogue — at least, more advanced than I’ve got, anyway. [Editor’s Note: This could be somewhat worrisome, since I know this reviewer has a Ph.D. in chemical engineering!] This is a book that had me bouncing out of my chair to look up unexplained references (things like thermotropic reactions, Cepheid stars, and Mollweide projections) a lot more often than I’m used to. There’s even a critical plot point that requires the reader to know what nitrogen triiodide monoammate is (it’s a type of explosive).

The editorial comment was inserted by SF Site editor Neil Walsh. ruining my little in-joke to my fellow chemical engineering grad students. Way to go, Neil.

Clement’s late 21st Century, as imagined in Half Life, was an SF fan’s paradise, filled with characters who quoted Heinlein the way we quote Shakespeare, and who had an encyclopedic knowledge of Golden Age pulp SF heroes like Morey and Wade, John W. Campbell’s intrepid scientist-adventurers from The Black Star Passes (1930) and Islands of Space (1931). It’s no wonder Golden Age SF fans loved him.

Clement’s late 21st Century, as imagined in Half Life, was an SF fan’s paradise, filled with characters who quoted Heinlein the way we quote Shakespeare, and who had an encyclopedic knowledge of Golden Age pulp SF heroes like Morey and Wade, John W. Campbell’s intrepid scientist-adventurers from The Black Star Passes (1930) and Islands of Space (1931). It’s no wonder Golden Age SF fans loved him.

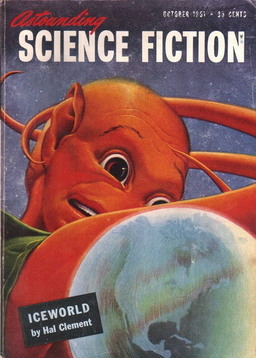

Clement’s real heyday was the 1950s, when he was a star in the pages of Astounding Science Fiction with lengthy serials like Iceworld (1951), in which a resourceful interplanetary narcotics agent must find a way to work with the inhabitants of a lethally cold planet to stop the spread of a dangerous new drug (tobacco). Of course, the incredibly cold planet is Earth, and most of the novel is told from the perspective of the alien agent.

Clement followed Iceworld with Mission of Gravity (serialized in the April–July 1953 Astounding), perhaps his most popular novel, and many others, including Cycle of Fire (1957), Close to Critical (1958), Mission of Gravity sequel Star Light (1971), Ocean on Top (1973), Through the Eye of a Needle (1978), The Nitrogen Fix (1980), and Fossil (1993). His final novel was Noise (2003).

Clement’s first short story, “Proof,” was published in the June 1942 issue of Astounding Science-Fiction, edited by John W. Campbell, Jr. Dozens more followed, exclusively in Astounding for the first decade of his career, until he sold “Halo” to H.L. Gold at Galaxy in 1952. He serialized his first novel, Needle, in the pages of Astounding in 1949.

Clement didn’t win a lot of awards for his work, but that didn’t mean he wasn’t appreciated. In 1998, he was inducted into the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame. The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America awarded him the Grand Master Award at the Nebula ceremonies in 1999.

His 1945 short story, “Uncommon Sense,” received a Retro Hugo, awarded 50 years after it was published, at the 1996 World Science Fiction Convention.

The Best of Hal Clement collected ten short stories published between 1942 and 1976, including “Uncommon Sense.” His early Astounding work is well represented (six stories), but there’s also later work from Worlds of If, Stellar, and other sources.

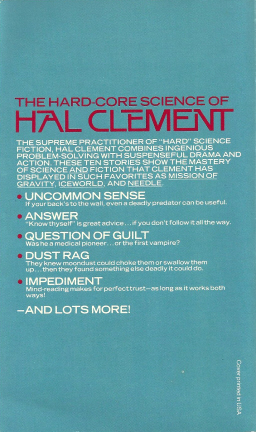

In the marketing copy on the back of the book Del Rey played up the hard SF angle, saying

The supreme practitioner of “hard” science fiction, Hal Clement combines ingenious problem-solving with suspenseful drama and action.

Here’s a scan of the back cover text (click for a bigger version), with the complete blurb and Del Rey’s trademarked short story teasers:

And here’s the complete contents:

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Hal Clement: Rationalist by Lester del Rey

“Impediment” (Astounding Science Fiction, Aug 1942)

“Technical Error” (Astounding Science Fiction, Jan 1944)

“Uncommon Sense” (Astounding Science Fiction, Sept 1945)

“Assumption Unjustified” (Astounding Science Fiction, Oct 1946)

“Answer” (Astounding Science Fiction, April 1947)

“Dust Rag” (Astounding Science Fiction, Sept 1956)

“Bulge” (If, Sept 1968)

“Mistaken for Granted” (Worlds of If, Jan-Feb 1974)

“A Question of Guilt” (The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series IV, Nov 1976)

“Stuck With It” (Stellar #2, Feb 1976)

“Author’s Afterword,” by Hal Clement (1979)

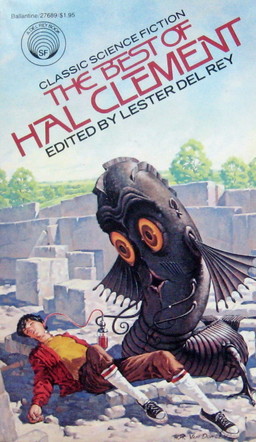

The Best of Hal Clement was published by Del Rey Books in June, 1979. It is 379 pages in paperback, originally priced at $1.95. It is out of print; there is no digital edition. The splendid cover — one of my favorites in the series — was by H.R. van Dongen.

The last volume in the Classic Library of Science Fiction we examined was The Best of Jack Williamson. So far we’ve covered (in order of publication):

The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum

The Best of Fritz Leiber

The Best of Henry Kuttner

The Best of John W. Campbell

The Best of C M Kornbluth

The Best of Philip K. Dick

The Best of Fredric Brown

The Best of Edmond Hamilton

The Best of Murray Leinster

The Best of Robert Bloch

The Best of Jack Williamson

The Best of Hal Clement

The Best of James Blish

The Best of John Brunner

See all of our recent Vintage Treasures here.

Funny to see this … I remember Hal the same way you did, as a friendly older fellow who regularly spoke at conventions here in Roanoke. I even got to share a panel or two with him. Much as my wife and I enjoyed his company (and that of his wife,) I started a couple of his novels and never made it past the first chapters.

To elaborate: I think that much of my inability to connect with his writing had to do with his compunction to put scientific accuracy above all else. He let me read the first chapter of his novel Fossil before it was published. The prose was pretty technical and rather wooden, and most of the chapter was devoted to a character’s apparent pratfalls: while talking to a colleague, the guy makes a wrong move (in a low gravity environment) and ends up tumbling and bouncing all over the place. I relayed to Hal that I found that sequence funny, which seemed to puzzle him — his goal was simply to portray as accurately as possible what happens when someone moves too fast in low gravity. He meant it to be instructional, not entertaining, heh.

> He meant it to be instructional, not entertaining, heh.

Mike,

I think you’ve perfectly encapsulated the essence of Hal Clement’s fiction in that one line.

Hal has his fans — and he was very popular in the pages of Astounding in the 50s and 60s — but, as fans before me have pointed out, the days when the core of SF was made up of engineers and young science enthusiasts are over.

SF today is more popular that ever, but to get there it had to move out of that narrow niche. In doing so I think it left writers like Hal Clement behind. Not a single one of his novels is in print today (although small presses like NESFA still have stock of his ESSENTIAL HAL CLEMENT collections from the 90s, and I think Orb hasn’t sold out of the CLASSIC MESKLIN STORIES volume originally released in 2002).

I think the following says a lot about my tastes in reading: this review in no way enticed me to seek out or try reading any Hal Clement.

I don’t think it was a bad review, Clement just doesn’t sound very compelling to me.

James,

I hope that won’t put you off any of the other authors in the CLASSICS OF SCIENCE FICTION series. Really, there’s something for everyone. 🙂

@John

No, not the case. I’ve bought and read the Robert Bloch and Stanley Weinbaum books. And I’m currently reading the Kornbluth book (though I’m having a harder time getting into it). Edmond Hamilton is in the mail on the way right now. I’m slowing attempting to read at least most of them.

Clement is definitely not for everybody, but he’s worth reading if you have the science background for it. I wouldn’t mind seeing more of this kind of fiction, but then I work in the sciences.

John, I’m surprised you think Clement was the least well-known of the authors who appeared in this series. I would think that honor (?) would go to Raymond Z. Gallun. Maybe things were different in the US in the late 70s. I had no trouble finding several of his novels in print at the local Waldenbooks, and there were additional titles to be had in used bookstores. This would have been about 1978-1980.

My memories of him are similar to yours. Clement was a guest at Conestoga and continued to attend every year from that point on until his death. I was making the circuit in the dealers’ room one year, and someone was coming along behind me whistling. I looked back to see Hal Clement perusing the wares and thoroughly enjoying himself as he whistled.

James,

Wow, that’s quite a reading project! We have a lot more books to go, so I hope you don’t burn out before we get to Leigh Brackett and John W. Campbell. 🙂

Pardon the second comment, but this one is on a little different topic than the first. John, you thought Clement was the least well known of the authors in the series, while I thought it would have been Gallun. There were other authors who wrote at the same time (1930s-1950s) who didn’t have a volume. Some, I’m sure, didn’t because of contractual reasons with other publishers. (I’m thinking of Heinlein here, although I don’t know for a fact that was the reason in his case.)

Do you have any knowledge of how Lester Del Rey went about selecting the authors for this series? For example, I would have thought Ross Rocklynne would have been better known (and a better choice) than Gallun, although not a better choice than Clement. Other than “Old Faithful”, Gallun didn’t produce much work of note. Certainly not much that held up over time, even by 1970s standards. Compared to Gallun, Clement was vastly superior in both style and content.

However, I should probably save my comments for when you get to Gallun.

> I’m surprised you think Clement was the least well-known of the authors who appeared in this series. I would think that honor (?) would go to Raymond Z. Gallun

Keith,

Yeah, I dithered a bit before making that claim, and Gallun was the other clear candidate. But I eventually made the call based on personal experience.

I first encountered Raymond Z. Gallun in BEFORE THE GOLDEN AGE, and his 1974 paperback The Eden Cycle (and his later novel Bioblast, in 1985), so his name wasn’t totally unfamiliar to me by the time I came across his collection.

Clement, though, was a total unknown to me (except for his convention appearances). I came across his paperbacks after I purchased his BEST OF book.

Looking at the evidence, I think you’re probably right that Clement was much more well known than Gallun to most readers. My experience probably wasn’t typical.

John,

Like you I also encountered Gallun in BEFORE THE GOLDEN AGE. I never saw any of his other work until the 80s, and that includes his BEST OF volume.

It’s interesting how different writers are better/less familiar to readers depending on which country you’re looking at. Or even which part of the country. We moved in 1980, and I didn’t see some of the later BEST OF paperbacks for years, being familiar with them only from the SFBC editions.

> Do you have any knowledge of how Lester Del Rey went about selecting the authors for this series? For example, I would have thought Ross

> Rocklynne would have been better known (and a better choice) than Gallun, although not a better choice than Clement.

Keith,

Fascinating question. And you’re absolutely right that Del Rey’s choices look a little mystifying on the surface. Where’s Heinlein, Asimov, and Arthur C. Clarke? For that matter Ray Bradbury, Jack Vance, Robert Silverberg, Poul Anderson, Ursula K. Le Guin, Theodore Sturgeon, Keith Laumer, or Harlan Ellison?

I don’t have much in the way of real information, but I do have some hunches. Obviously, most of Heinlein, Asimov and Clarke’s early SF was already tied up with other publishers by the time Del Rey cooked up the BEST OF line, so the rights simply weren’t available.

But why pick Raymond Z. Gallun and Hal Clement over (say) Ray Bradbury and Jack Vance? Well, that’s easy. Ballantine Books/Del Rey published Gallun’s THE EDEN CYCLE and Hal Clement’s ICEWORLD and MISSION OF GRAVITY. Vance was published by DAW, and Bradbury by Avon. At that point in the series, Del Rey was simply promoting his own house authors.

Interestingly, DAW picked up on this strategy in the late 70s, publishing THE BOOK OF JACK VANCE, THE BOOK OF KEITH LAUMER, etc. to showcase their own authors. There weren’t as many as Del Rey’s (and the packaging wasn’t nearly as attractive), but it was still a fine effort.

Pocket also had a BEST OF series about that time, and Jack Vance was included in that one along with Keith Laumer, Damon Knight, Harry Harrison, John Sladek, Poul Anderson, Robert Silverberg, Barry N. Malzberg, Mack Reynolds, and maybe some others. That’s all I recall off the top of my head. Except for the Reynolds and Malzberg entries, they weren’t as thick as the Del Rey volumes, but they still had some good stories.

Leiber had two volumes in DAW’s series, which I think makes him the only author to be in both.

Your explanation about Del Rey promoting his own line makes a lot of sense. I don’t understand why Sturgeon wasn’t included as Del Rey published a few of his titles.

Keith,

You’re right, it was Pocket that published Vance and Laumer, not DAW.

Your memory is clearly superior to mine, as there’s no way I could have recalled that many authors in their line from memory! But you missed my favorite volume – THE BEST OF WALTER C. MILLER. Loved the cover of that one too, with the couple riding the beetle:

And yeah, I think Leiber was the only author to be part of both series. I remember thinking it was odd at the time. 🙂

I knew there was one I was leaving out. I’ve got all of the Ballantine BEST OFs and all I know of from the Pocket series, plus a few others from different publishers. They’ve got their own shelf space, which is how I remembered most of them. They were a great way to find out if I would like a particular author.

When I still worked for the evil empi…I mean Barnes & Noble, I had one of NESFA Hal Clement volumes on shelf, and a grizzled old engineer wanted the other volume of stories ordered. He would only give his Ham Radio callsign as customer contact information for the order.

John, do you have any plans to look at the Best of volumes from other publishers when you’re done with the Del Reys?

[…] no accident. He’s come up multiple times in this series so far. In my last article, The Best of Hal Clement, I noted that Clement’s heroes frequently quoted Campbell’s pulp heroes Morey and Wade, […]

[…] The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum The Best of Fritz Leiber The Best of Henry Kuttner The Best of John W. Campbell The Best of C M Kornbluth The Best of Philip K. Dick The Best of Edmond Hamilton The Best of Murray Leinster The Best of Robert Bloch The Best of Jack Williamson The Best of Hal Clement […]

[…] we’ve discussed in the Comments section of previous posts, Lester Del Rey’s Classics of Science Fiction library is perhaps the finest mass […]

[…] of Edmond Hamilton The Best of Murray Leinster The Best of Robert Bloch The Best of Jack Williamson The Best of Hal Clement The Best of James […]

[…] of Edmond Hamilton The Best of Murray Leinster The Best of Robert Bloch The Best of Jack Williamson The Best of Hal Clement The Best of James […]

[…] of Edmond Hamilton The Best of Murray Leinster The Best of Robert Bloch The Best of Jack Williamson The Best of Hal Clement The Best of James […]

[…] of Edmond Hamilton The Best of Murray Leinster The Best of Robert Bloch The Best of Jack Williamson The Best of Hal Clement The Best of James […]