Yes, Virginia, There is a Cthulhu

Last week I wrote about the famous editorial penned by Francis Church in response to a query by a girl named Virginia O’Hanlon as to whether there is a Santa Claus. Re-reading “Is there a Santa Claus?”, I was struck by a curious correspondence between part of Church’s argument and the very first paragraph of one of H.P. Lovecraft’s most famous stories, “The Call of Cthulhu.” I’ll run the relevant excerpts from Church, followed by the Lovecraft paragraph. See for yourself:

Last week I wrote about the famous editorial penned by Francis Church in response to a query by a girl named Virginia O’Hanlon as to whether there is a Santa Claus. Re-reading “Is there a Santa Claus?”, I was struck by a curious correspondence between part of Church’s argument and the very first paragraph of one of H.P. Lovecraft’s most famous stories, “The Call of Cthulhu.” I’ll run the relevant excerpts from Church, followed by the Lovecraft paragraph. See for yourself:

“…All minds, Virginia, whether they be men’s or children’s, are little. In this great universe of ours man is a mere insect, an ant, in his intellect, as compared with the boundless world about him, as measured by the intelligence capable of grasping the whole of truth and knowledge… The most real things in the world are those that neither children nor men can see… Nobody can conceive or imagine all the wonders there are unseen and unseeable in the world. You may tear apart the baby’s rattle and see what makes the noise inside, but there is a veil covering the unseen world which not the strongest man, nor even the united strength of all the strongest men that ever lived, could tear apart.” (Church 1897)

“The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.” (Lovecraft 1928)

Hmmm. Man is a mere insect in his intellect, unable to grasp the whole of truth and knowledge. His mind is unable to correlate all its contents. We are ignorant, in black seas of infinity, unable to peer through the veil covering the unseen world… See what I did there? Pretty much jumbled them together, and they are of a piece.

The shared premise, I think, is what Shakespeare succinctly expressed through the character of Hamlet four centuries ago: “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy” (Shakespeare 1602).

The correspondence between the Christmas editorial and “The Call of Cthulhu” is undoubtedly coincidental, and there are two salient differences in the discordant philosophies expressed in both texts. Church asserts that we can only gain glimpses through that veil of ignorance via “faith, fancy, love, poetry, romance,” whereas Lovecraft suggests the sciences are drawing back the veil. And, of course, Church posits the hidden “supernal beauty and glory beyond” as a good thing. Lovecraft, most assuredly, portrays those “terrifying vistas of reality, and our frightful position therein,” as a bad thing. A very, very bad thing.

Both views resonate with me; I, perhaps contradictorily, sympathize with both. What does that say about me?

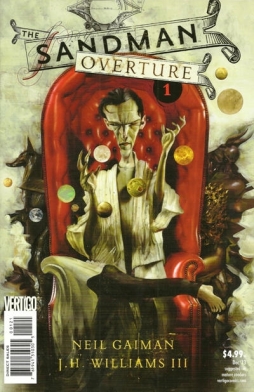

Late last October, the first issue of Sandman: Overture reached comic store shelves. The start of a new bimonthly six-part story, with art by J.H. Williams III, it’s a prologue to writer Neil Gaiman’s widely-acclaimed Sandman series, which ran for 75 issues (plus a special, some spin-off miniseries, a novella, and a collection of short comics stories) from 1988 to 1996. The series built in popularity as it went on and seems to have continued to find an audience in the years since its conclusion. It’s sustained a level of commercial appeal — perhaps as much as any single comic series, it helped to create the contemporary market for trade paperbacks — while also drawing critical praise, both inside and outside of comics. Issues or storylines of the main series were repeatedly nominated for the British Fantasy Awards, and once for the Stoker, while one issue won the 1991 World Fantasy Award.

Late last October, the first issue of Sandman: Overture reached comic store shelves. The start of a new bimonthly six-part story, with art by J.H. Williams III, it’s a prologue to writer Neil Gaiman’s widely-acclaimed Sandman series, which ran for 75 issues (plus a special, some spin-off miniseries, a novella, and a collection of short comics stories) from 1988 to 1996. The series built in popularity as it went on and seems to have continued to find an audience in the years since its conclusion. It’s sustained a level of commercial appeal — perhaps as much as any single comic series, it helped to create the contemporary market for trade paperbacks — while also drawing critical praise, both inside and outside of comics. Issues or storylines of the main series were repeatedly nominated for the British Fantasy Awards, and once for the Stoker, while one issue won the 1991 World Fantasy Award.