Sandman: An Overture And A Look Back

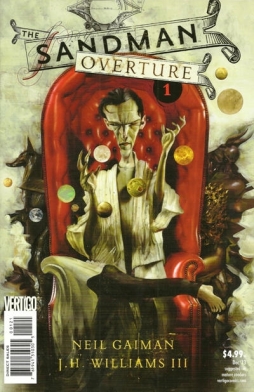

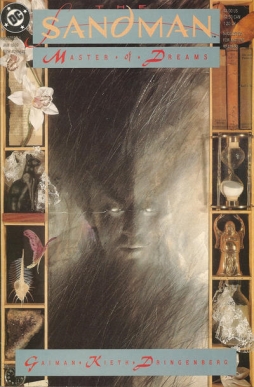

Late last October, the first issue of Sandman: Overture reached comic store shelves. The start of a new bimonthly six-part story, with art by J.H. Williams III, it’s a prologue to writer Neil Gaiman’s widely-acclaimed Sandman series, which ran for 75 issues (plus a special, some spin-off miniseries, a novella, and a collection of short comics stories) from 1988 to 1996. The series built in popularity as it went on and seems to have continued to find an audience in the years since its conclusion. It’s sustained a level of commercial appeal — perhaps as much as any single comic series, it helped to create the contemporary market for trade paperbacks — while also drawing critical praise, both inside and outside of comics. Issues or storylines of the main series were repeatedly nominated for the British Fantasy Awards, and once for the Stoker, while one issue won the 1991 World Fantasy Award.

Late last October, the first issue of Sandman: Overture reached comic store shelves. The start of a new bimonthly six-part story, with art by J.H. Williams III, it’s a prologue to writer Neil Gaiman’s widely-acclaimed Sandman series, which ran for 75 issues (plus a special, some spin-off miniseries, a novella, and a collection of short comics stories) from 1988 to 1996. The series built in popularity as it went on and seems to have continued to find an audience in the years since its conclusion. It’s sustained a level of commercial appeal — perhaps as much as any single comic series, it helped to create the contemporary market for trade paperbacks — while also drawing critical praise, both inside and outside of comics. Issues or storylines of the main series were repeatedly nominated for the British Fantasy Awards, and once for the Stoker, while one issue won the 1991 World Fantasy Award.

Why did the comic become so important? What does it do so well? And does it look like the new series can hold up? I want to take a stab at answering those questions, in reverse order. There’s a lot to be said about Sandman, and this really scratches the surface of possible interpretations; but for what it’s worth, this is the framework in my head when I look at the comic.

To start with the new stuff: the first issue’s incredibly promising. It’s a prequel that looks to tell a story worth telling — a story that answers an unanswered question from the main tale. The original Sandman series began with the main character, Dream of the Endless, also known as Morpheus, captured by a group of occultists in the early 20th century. We later find out that Dream’s a fundamental force of the cosmos, one of a group of more-than-godly siblings; so how did a group of semi-accomplished would-be wizards manage to imprison him? This new miniseries, it seems, will describe the conflict which weakened Dream to the point where he could be held for decades in a glass prison.

And it gets off to a good start. Familiar characters from the original series reappear, sounding like themselves, and serving relevant purposes — they’re not wheeled onstage for the sake of familiarity, they have reasons for being who they are and where they are. At the same time, the ending gatefold-splash page promises a major saga that will do some surprising things. Gaiman’s gift for language and ability to evoke the surreality of dreams is on display. It feels tonally like a continuation of the original series without a step missing.

And it gets off to a good start. Familiar characters from the original series reappear, sounding like themselves, and serving relevant purposes — they’re not wheeled onstage for the sake of familiarity, they have reasons for being who they are and where they are. At the same time, the ending gatefold-splash page promises a major saga that will do some surprising things. Gaiman’s gift for language and ability to evoke the surreality of dreams is on display. It feels tonally like a continuation of the original series without a step missing.

Williams didn’t work on the first run of Sandman, but his art here fits perfectly with the aesthetic of the series, and in fact promises to be one of the best visual renditions of Dream and his world. Sandman gained a lot from the variety of artists the title saw over the course of its run, but it has to be said that not every artist or art team was successful. Williams, one of the most inventive storytellers in contemporary mainstream comics, takes his place at once near the forefront of Dream interpreters. His page layouts are striking and his ability to move from realism to surrealism to fantasy is perfect for this title. The concluding images of the first issue, where a range of figures are depicted in a variety of styles, is a perfect example.

So the first issue’s a highly promising return to the series, worth the $4.99 price tag. A “special edition” was published in November, featuring an interview with Williams; subsequent issues will also be given special editions, which will ship one month after the original printing of the issue. It’s worth noting that the second issue’s already been delayed to February, due to knock-on effects from an extended book tour Gaiman undertook last year; there’s something familiar about that, as the original series was plagued by delays, especially later in its run. But with all that said, what was it that made the original series stand out so much? Why is it so celebrated and why is this return to Dream so significant?

It seems to me that the series is so powerful because it dared greatly, and in many ways succeeded. It’s a story about stories, about the shapes of stories and how stories work and how stories matter and how stories may be changing their shapes. It’s a myth about myths. In order to be convincing, the series needed to be broad, it needed to be wide-ranging, and yet at the same time it needed to be simple: to have a central clear idea. It managed all this, by being cunning in its shape.

It seems to me that the series is so powerful because it dared greatly, and in many ways succeeded. It’s a story about stories, about the shapes of stories and how stories work and how stories matter and how stories may be changing their shapes. It’s a myth about myths. In order to be convincing, the series needed to be broad, it needed to be wide-ranging, and yet at the same time it needed to be simple: to have a central clear idea. It managed all this, by being cunning in its shape.

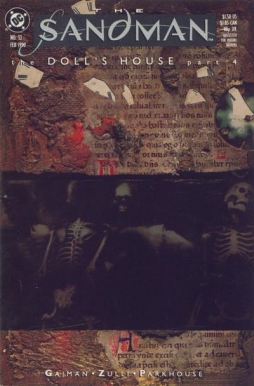

Gaiman structured the comics series cleverly, alternating long multi-issue stories and short thematically-linked single-issue tales. The longer stories tended to focus on Dream himself as a major character, and on his kingdom and relations and enemies. So did many of the short stories, but many of them, perhaps the best of them, were also more elliptical — ranging across time and space, to other worlds and might-have-been worlds, to present stories in which Dream featured as a relatively minor character. At first, you notice the splendid invention in the series, the range of settings and characters: Imperial Rome, Harun al-Rashid’s Baghdad, the French Revolution, an alternate world where an obscure DC Comics character becomes a teenaged President of the United States. But then, when you’ve read through the whole series, you see how the individual short pieces connect up to the larger story: how they illuminate some aspect of Dream’s character or nature, set up plot points, establish theme — often all at once.

The structure of the individual stories were usually as unexpected as they were well-constructed. Gaiman found a particularly useful shape for his longer arcs: he’d often break away from the main action for an issue at some point in the middle, and reflect on the central plot from an unexpected viewpoint. Sometimes he may have pushed it too far — “Men of Good Fortune,” in issue 13, is a wonderful story in which Dream makes a friend who he meets once every century; but it reads like a strange disruption in the longer storyline, The Doll’s House, of which it is nominally a part. But overall it emphasised the structural mastery Gaiman brought to the series.

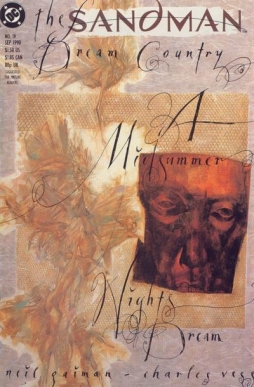

Without going into too much detail, the book is overall a story about the shaper of stories finding a shape for his own story. That shape is an old shape, reaching back to Aeschylus and Greek myth; it’s a tragedy, and those Greek echoes are well-earned. Nor is it surprising that Shakespeare turns up as a character — a Shakespeare of the romances and fantasies primarily, but with echoes of the writer of Hamlet not far below the surface. There’s something inherently and self-consciously theatrical about Dream and his world.

Without going into too much detail, the book is overall a story about the shaper of stories finding a shape for his own story. That shape is an old shape, reaching back to Aeschylus and Greek myth; it’s a tragedy, and those Greek echoes are well-earned. Nor is it surprising that Shakespeare turns up as a character — a Shakespeare of the romances and fantasies primarily, but with echoes of the writer of Hamlet not far below the surface. There’s something inherently and self-consciously theatrical about Dream and his world.

To an extent, that also points up one of the problems I have with the series: the characters are on the whole rather broader than they are deep. The theatricality of the work sometimes works against it on this score, as characters are given lines a little too on-the-nose, a little too self-evidently wise. It’s a difficult line to find; overall, again, I think the short stories tend to come off better on this score, as their character-building seems more tightly integrated into their various structures. I will say that I think this approach to character created one of the most unintentionally chilling elements of the book, in Dream’s older sister Death, a peppy Valley girl who claims to understand mortal beings inside and out while displaying no actual grasp of life: a new horror to death, this, a patronising self-absorbed grinning inhuman psychopomp.

My friend Tom Crippen once observed in an essay for The Comics Journal that the characters in the series have a particular kind of super-power: the power to matter more than others. There’s something to that, I think. The series, and Dream’s own outlook on the universe, is relentlessly hierarchical. You know who is a major character and who is a minor character; you know who will be given the knowing lines, the words we are meant to take for wisdom. Sometimes it’s a convincing wisdom and sometimes it isn’t, but the structure of the story often leads us to accept as profound ideas that ought not to work.

I wonder, though, if that tendency to hierarchy is meant to be undermined by the end of the book; if the promised renewal at the end suggests a more open kind of cosmology of story. One of the consistent themes in the book is the abandoning of old ideas of oneself as a necessary step leading to growth and development into something larger and truer (we are told at a key point that old gods don’t die, don’t move on, but hang around a “dream country” of the mind; there’s something pathetic in that, is the point). I find that theme emerges in the ending of the book. And I think that’s meant to imply that our ideas of stories are changing. If Dream is surrendering the idea of mattering, then perhaps story shapes are abandoning the things we used to think mattered as well. Tastes change. Times change. Stories change with them. As a specific example, Dream’s story frequently seems to imply gender essentialism, and certainly Dream’s own vexed relationship with the opposite gender may be seen as affecting the way we conceive of our narratives of gender; so the changes at the end of the book perhaps reflect the possibility of changes in those gender stories, perhaps even an undoing of the gendering of stories as whole.

I wonder, though, if that tendency to hierarchy is meant to be undermined by the end of the book; if the promised renewal at the end suggests a more open kind of cosmology of story. One of the consistent themes in the book is the abandoning of old ideas of oneself as a necessary step leading to growth and development into something larger and truer (we are told at a key point that old gods don’t die, don’t move on, but hang around a “dream country” of the mind; there’s something pathetic in that, is the point). I find that theme emerges in the ending of the book. And I think that’s meant to imply that our ideas of stories are changing. If Dream is surrendering the idea of mattering, then perhaps story shapes are abandoning the things we used to think mattered as well. Tastes change. Times change. Stories change with them. As a specific example, Dream’s story frequently seems to imply gender essentialism, and certainly Dream’s own vexed relationship with the opposite gender may be seen as affecting the way we conceive of our narratives of gender; so the changes at the end of the book perhaps reflect the possibility of changes in those gender stories, perhaps even an undoing of the gendering of stories as whole.

And it is important to note, I think, that Dream is consistently made into a representative not of dreams alone, but of story, of myth. His captivity through the course of the 20th century seems also to be meant to imply something about the century, about how and why it went so wrong. It’s a daring conceit, largely unexplored, but more powerful for being implied rather than stated outright.

Which also points up what may be most impressive about Gaiman’s structural dexterity: the way he’s able to subtly integrate themes, to make points unobtrusively, to unite stories and motifs through ways other than direct plot. His sequences of short stories have a coherence to them that makes them all unities, even when the elements they share are not immediately apparent. Gaiman’s able to command a true symbolism: he’s able to invest images with meanings beyond anything that can be enunciated, so that the more you look at them the more you see in them. And he ties together his sprawling material with echoes, with patterns of event: so the various rulers of various kingdoms we see in the short stories of Distant Mirrors seem to be echoes of Dream himself, finding the shapes of their kingdoms and establishing them as fictions; while Dream’s creation of the vicious nightmare called the Corinthian oddly echoes Lucifer’s creation and fall (and the equivocal redemption that comes to him in the pages of Sandman).

So do all these qualities of the book explain why the series became so important? Well, no. There was, I think, an element of serendipity to Sandman’s success. I don’t think it minimises the quality of his writing to observe that Gaiman was the right writer in the right place at the right time. The environment in which the book was published was, in retrospect, primed for something just like this.

So do all these qualities of the book explain why the series became so important? Well, no. There was, I think, an element of serendipity to Sandman’s success. I don’t think it minimises the quality of his writing to observe that Gaiman was the right writer in the right place at the right time. The environment in which the book was published was, in retrospect, primed for something just like this.

Gaiman’s observed that he and the generation of British comics writers that crossed the Atlantic in the wake of Alan Moore’s success at DC were like the English rock bands that made it over to North America in the wake of the Beatles. At the time Sandman began, Gaiman was effectively unknown to the vast majority of his audience: he’d written biographies of Douglas Adams and Duran Duran, a couple of short stories, and various pieces of journalism and magazine articles. With Kim Newman, he’d put together a collection of humorous quotations of bad writing from schlock genre books. Then he’d begun to write comics in England: short “Future Shocks” for 2000 AD, short pieces for a collection called Outrageous Tales From the Old Testament — one of which was his first collaboration with artist Dave McKean — and then, with McKean, an excellent graphic novel, Violent Cases. These works led to his being hired by DC, for whom he wrote a three-issue prestige-format miniseries Black Orchid. And then Sandman.

The comics industry in North America was in an odd state (as it usually seems to be). It had recently moved from being dominated by newsstand retailers to direct-market comics stores, which had the overall effect of spurring the growth of independent comics. Sandman was published by one of the ‘mainstream’ publishers, but insofar as its sensibility resembled anything else on the market, it was probably closest to the ‘ground-level’ independent comics of the time — not underground, but distinct from typical superhero comics. Sandman had certain distant links to the DC cosmology, visible mostly in the first few issues, but rapidly moved away from them. (Ironically, the DC universe Sandman referred to is now no longer ‘existent,’ as the DC continuity’s been rewritten several times since then. In the language of mainstream comics, Sandman’s arguably the last post-Crisis pre-Flashpoint DC book still being published.)

Gaiman certainly brought a knowledge of literary and storytelling traditions to the book that was unusual for North American comics. Sandman was multicultural, and also influenced by myth and legend in a deeper way than most comics — rather than trying to interpret myth in a super-heroic idiom, it seemed to try to channel the power of myth into a contemporary fantasy story. It wasn’t afraid of the old roots of its stories, and acknowledged them in ways few other comics seemed interested in doing. It was not afraid of being a literate book.

Gaiman certainly brought a knowledge of literary and storytelling traditions to the book that was unusual for North American comics. Sandman was multicultural, and also influenced by myth and legend in a deeper way than most comics — rather than trying to interpret myth in a super-heroic idiom, it seemed to try to channel the power of myth into a contemporary fantasy story. It wasn’t afraid of the old roots of its stories, and acknowledged them in ways few other comics seemed interested in doing. It was not afraid of being a literate book.

The series did fairly well out of the gate, and kept increasing sales. In late 1993 Gaiman said in an interview with The Comics Journal that:

Sandman #1 did about 89,000 [sales], which for the time was incredibly good, although I didn’t quite know that at the time. In terms of the best-selling Swamp Thing, which was really the only benchmark, the last ever Alan Moore/Steve Bissette Swamp Thing had done I think about 64,000 or 65,000. So we did 89-ish on Sandman #1, 65-ish on Sandman #2, Sandman #3 was down in the 40s, then Sandman #4 I think was in the 40s but maybe a little bit more, Sandman #7 had crept back into the low-50s, and I think we stayed in the 50s … After about Sandman #7 we basically would pull in something like 500 to 1000 issues a month, a very slow climb up to about issue #31 where we were in the 60s. We got healthily in the 60s, and there was a big push at 32 and we went into the 80s and stayed in the 80s and hung around there until the Vertigo push [the creation of DC’s Vertigo imprint] at which point we moved comfortably into the 100s and have stayed there. … [C]urrently we’re somewhere around 110 and that’s pretty much where we’ve been.

The Vertigo imprint was a creation of DC comics in 1993, which incorporated Sandman and other books of a similar sensibility. Gaiman’s book was the flagship title of the line, as he observed:

It’s obviously a flagship title, it’s a commercial success. It would appear to have, to some extent, created its own readership, which is a nice thing to have, which is to say that an awful lot — not all by any means — of Sandman readers weren’t comic readers. … These are people who don’t read comics — somebody just showed them a copy of this one day and they really like it and they go and get it. And very often they haven’t even made the mental leap that this is a comic and there are other things out there that are like it.

That ability of the book to create its audience, and to find an audience among readers otherwise indifferent to comics, became especially clear once the trade paperback format took off. One could probably argue that Sandman was in fact one of the key elements in establishing the trade paperback format for comics (or “graphic novels”): a popular, critically-praised multivolume series that can be read as individual books but which gains from being read as a whole in sequence. As the comics market tried to reach beyond its traditional fan base, as it tried to expand into bookstores, Sandman became a real breakout hit. Diamond Comic Distributors states on its web site that the series is: “Arguably the most successful graphic novel series in the United States so far … there are currently 10 volumes with estimated sales of over one million copies.”

(As it happens, in the same Comics Journal issue I quoted from above, there’s also a round-table interview with some Vertigo writers and Vertigo’s founding editor, Karen Berger, in which Berger notes that DC is consciously trying to get trade paperback collections of Sandman and other Vertigo books into markets like Tower Records: “Actually, with Vertigo, we went into this thing expecting our books would do okay in the comic book world but shoot for a new reader and a new market. To be honest, it’s doing a lot better than I ever thought it would.”)

(As it happens, in the same Comics Journal issue I quoted from above, there’s also a round-table interview with some Vertigo writers and Vertigo’s founding editor, Karen Berger, in which Berger notes that DC is consciously trying to get trade paperback collections of Sandman and other Vertigo books into markets like Tower Records: “Actually, with Vertigo, we went into this thing expecting our books would do okay in the comic book world but shoot for a new reader and a new market. To be honest, it’s doing a lot better than I ever thought it would.”)

So the series was a good book, and at the right place at the right time. But there were other good books around; Gaiman himself has observed that he learned a lot about comics, and about the structure of long-form comics, from Alan Moore and Dave Sim — both of whom, by the early 1990s, had multiple-volume series either ongoing or already published (Cerebus for Sim, Swamp Thing and From Hell for Moore, to say nothing of Moore’s many single-volume works such as Watchmen and V For Vendetta). Was there anything else that singled out Sandman? It’s fair to observe that individual circumstances affected the back catalogue of both Sim and Moore — Moore’s difficulties with publishers, and Sim’s controversial social views. But there were other major creators around at the time: Scott McCloud, the Hernandez Brothers, even Wendy Pini with her long-running Elfquest — which had been sold in collections as early as 1981. Was there anything special singling out Sandman, beyond its having a major corporation behind it?

Well, maybe. This is the sort of question everyone can answer differently. Personally, I think it does a few things that I don’t recall seeing in comics at the time, and hits a certain tone. I think there’s an implicit affirmation running through the series, never enunciated or explicit, of the value of stories, of storytelling, of reading, of writing, of literacy. I think it states that knowing things is important, especially knowing things about the shape of stories. I think for many readers, especially readers in their teens and early 20s (and I was 15 when I read the first issue of the comic, so of course I’m writing here about my own experience), that is a powerful message.

I think that at the same time there’s both an exuberance and elegance to Gaiman’s writing. There’s an exuberance in the variety of characters and settings he uses; an exuberance in the range of stories and traditions he plays with. And I think there’s an elegance to the way he finds shapes for his narratives in among all that matter. One of the persistent (and valid) criticisms of the book is that Gaiman shies away from real conflict, from dramatic resolutions. That’s because he’s more interested in a different sort of story resolution, something you might see in fairy tales; in detective stories; or in the stories of G.K. Chesterton, who wrote both those things (and Chesterton, one of Gaiman’s favourite writers, lends his guise to one of Dream’s creations, Fiddler’s Green). It’s a mode of resolution that revolves around the revealing of the true state of affairs. There can be no conflict when everything’s sorted out because, once the world is properly understood, there’s no possible way for a conflict to bring anyone any good. The ‘true state of affairs’ may be very well hidden through most of the story, it may in fact be thoroughly inverted, but that only makes the revealing of the truth more satisfying when it happens. And that revelation comes not through battle, but through a kind of sleight-of-hand: a true magic act.

I think that at the same time there’s both an exuberance and elegance to Gaiman’s writing. There’s an exuberance in the variety of characters and settings he uses; an exuberance in the range of stories and traditions he plays with. And I think there’s an elegance to the way he finds shapes for his narratives in among all that matter. One of the persistent (and valid) criticisms of the book is that Gaiman shies away from real conflict, from dramatic resolutions. That’s because he’s more interested in a different sort of story resolution, something you might see in fairy tales; in detective stories; or in the stories of G.K. Chesterton, who wrote both those things (and Chesterton, one of Gaiman’s favourite writers, lends his guise to one of Dream’s creations, Fiddler’s Green). It’s a mode of resolution that revolves around the revealing of the true state of affairs. There can be no conflict when everything’s sorted out because, once the world is properly understood, there’s no possible way for a conflict to bring anyone any good. The ‘true state of affairs’ may be very well hidden through most of the story, it may in fact be thoroughly inverted, but that only makes the revealing of the truth more satisfying when it happens. And that revelation comes not through battle, but through a kind of sleight-of-hand: a true magic act.

Finally, I think what also makes the book work, something key to its appeal to audiences, is its mythopoeic power. That level of invention I’ve mentioned above; the creation of characters and settings and images that are both novel and archetypal, while also seeming like just the smallest slice of things. Just one bit of a much larger world. Gaiman’s comic works because it feels like part of something truly Endless: like there’s always more of it, always more material waiting to be made into story. And each page, each issue, each trade paperback, promises something new: something that will expand the reader’s sense of what is possible in this story. The first issue of the new series maintains that promise. It’s the best of reasons for looking forward to the rest.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Matthew, thanks for mentioning my old Gaiman article and thanks for writing this very useful and interesting overview of the series.

I was especially struck by your thoughts on the Sandman stories being gendered and how their wind-up might be pointing to a de-gendering of stories. Could you write a second piece, one just on those topics? I admit that my only thoughts on the subject are that Gaiman has always been Joe Feminist, w/ all the good and bad that implies. (Well, maybe not all the bad. I doubt he uses feminism to pick up chicks.)

On Death, I would say she’s indeed grinning and patronising, but I don’t see the self-absorbed and inhuman bit. She always makes a point of being so nice.

Finally, it’s great to hear that there’s a new Sandman series and that it’s good, and especially that the characters are there because the story calls for them. Kindly Ones was such an ordeal in large part because every supporting character seen earlier in the series had to get called back for an encore.

Thanks for the good words, Tom!

As far as the gendering of Sandman goes, I’d have to reread the whole series for a detailed discussion, and that’d take a while. [Spoilers for the series follow, for anyone else reading this!] I’m not sure what kind of final conclusion I’d have about it anyway. I think we’ve talked about some of it before: how the Kindly Ones are this really intensely mythically feminine creature, who turn up early in the story and end up bringing about the end (and then how you can get trios of female characters, like Foxglove/Hazel/Thessaly in A Game Of You, who seem to reflect that same trinity). How the stories in Worlds’ End are described as all ‘male’ stories, with the woman who makes that comment (named Mooney) doesn’t get a story herself. Arguably even how Dream makes himself vulnerable to the Kindly Ones by going to answer Nuala’s call. Things like that. I think there’s enough of these odd little bits worked through the series that there’s a coherent theme to be teased out of it.

In terms of Death, I always got the vibe of a slumming aristo who was patting herself on the back for talking to the proles like they were real people, you know? She’s nice because it doesn’t cost her or hurt her to be nice; because she’s higher-class than everyone around her, and knows it. I generally always figured the Endless to be a basically traditionally aristocratic family group: the oldest three being the ones most intent on keeping up their old feudal duties, attending sitting of the House of Lords or keeping up family investments or whatever, then Destruction the rebel who threw away (most of) his life of privilege and rejected the family, then Desire and Despair in different ways upset that they’re lower in the birth order and don’t stand to inherit all the nice stuff their elders did (which becomes transmuted into cruelty to those ‘below’ them), and then Delirium as the equivalent of the kid who spends her inherited cash on drugs and mind-altering substances. Make of it what you will.

[…] Then I used the first issue of the new Sandman: Overture limited series as a launching-point for a brief discussion of Sandman as a whole. I followed that with some words on Chris Moriarty’s incredibly impressive sf novel Spin […]