Vintage Treasures: The Astounding-Analog Reader edited by Harry Harrison and Brian W. Aldiss

|

|

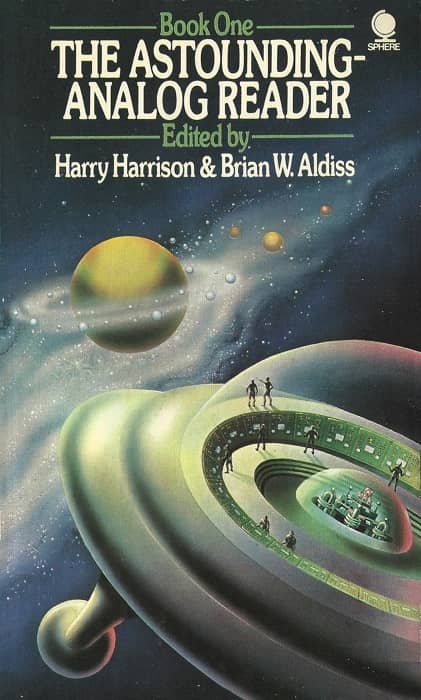

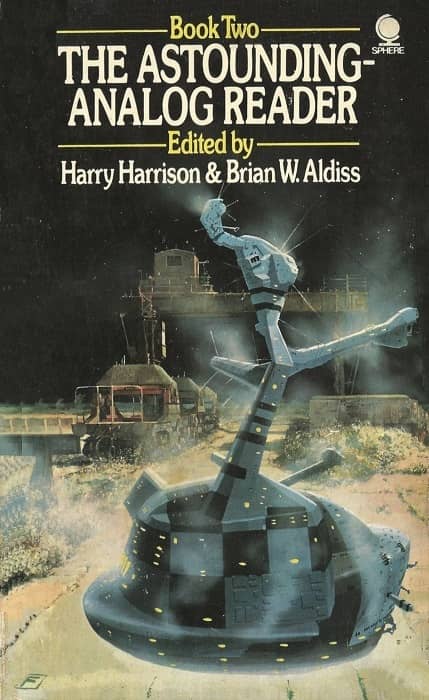

The Astounding-Analog Reader (Sphere 1972 and 1973). Covers by unknown (left) and Chris Foss (right)

I used to scoff at the idea of online bookstores. How will you browse for books?, I demanded to know. You’ll never replace that wonderful moment of discovery, of serendipity, finding a treasure you weren’t looking for, which happens all the time in great bookstores.

Of course, these days I find books online all the time. I’m a huge fan of Harry Harrison and Brian W. Aldiss’s top-notch science fiction anthologies, like the long-running The Year’s Best SF series and Farewell Fantastic Venus! But I had no idea they’d collaborated on a two-volume collection of Golden Age pulp SF, The Astounding-Analog Reader, until I stumbled on a copy of the second volume on eBay a few weeks ago. I tracked down the first one, ordered both, and have been dipping into them ever since they arrived.

The Astounding-Analog Reader is a fantastic assortment of (generally longer) fiction from the pages of Astounding, circa 1937 — 1946. It was originally published in hardcover as The Astounding-Analog Reader, Volume 1 by Doubleday in 1972, and reprinted in paperback in the UK by Sphere as The Astounding-Analog Reader, Book 1 and Book 2 in October 1973. It has never has a paperback edition in the US.

The editors completed the series a year later with The Astounding-Analog Reader, Volume 2 (Doubleday, 1973), which contained stories from 1947-1965. That volume has never had a paperback edition, which makes me sad.