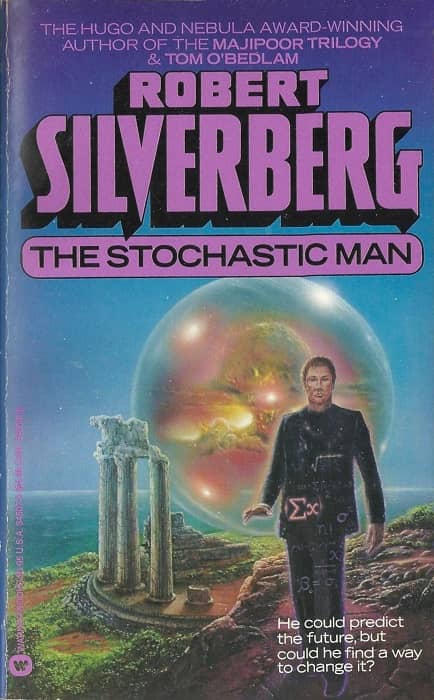

Vintage Treasures: The Stochastic Man by Robert Silverberg

|

|

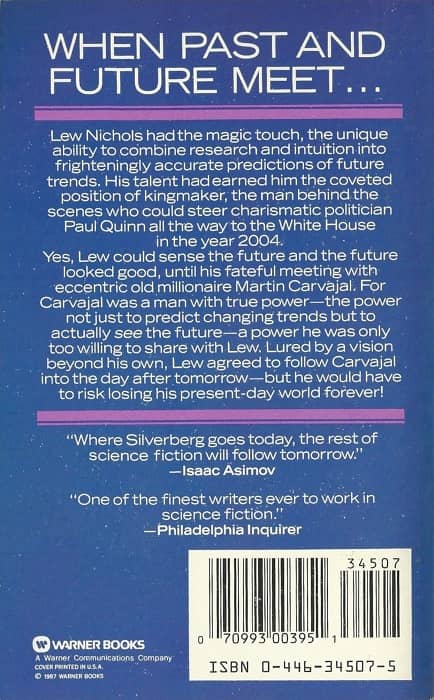

The Stochastic Man (Warner Books, 1987, cover art by Don Dixon)

Back in May I started a Vintage Treasures post about Robert Silverberg’s 1975 novel The Stochastic Man, and it wasn’t long before I’d unearthed nearly a dozen different editions. Pretty soon I got distracted comparing the art and author branding for each, and that led me down a deep rabbit hole that ended up with a very long article titled The Art of Author Branding: The Paperback Robert Silverberg.

That was fun, and very satisfying. But it never mentioned The Stochastic Man.

So today I grit my teeth, committed myself to a lot more focus, and started in again. Wish me luck.

The Stochastic Man was one of Robert Silverberg’s most popular and successful novels. It was originally serialized in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (April to June, 1975), and then published in hardcover by Harper & Row in September 1975. That year it was nominated for the Hugo, Nebula, Locus, and Campbell Memorial Award. After that it was packaged up by many publishers in the 70s and 80s, and enjoyed a long life and fruitful life in reprint editions from Fawcett Gold Medal, The Science Fiction Book Club, Coronet Books, Gollancz, Warner Books, Gateway/Orion, and others. It was reprinted in trade paperback just last year by ReAnimus Press.