Many Paths of Character Creation

|

|

For many RPG gamers, creating characters is one of the highlights of gaming. They get to make significant choices and craft and hone their character to their vision. If they are invested in the character, players typically engage more in the collaborative storytelling environment that RPGs are. For many players, this is the most creative time in the process, for thereafter they engage in the setting as laid out by the game master (GM). They may have an influence on the game and that setting, but the act of creating primarily — if not exclusively — resides with the GM after character creation. Even in truly sandbox games where the players can go wherever and do whatever, they are operating within the construct of the GM.

RPGs across the spectrum devote pages to character creation, often taking up a significant portion of any rulebook and entire supplements that provide new options. Most games lay out these options as a series of choices the player makes — though always reserving GM fiat.

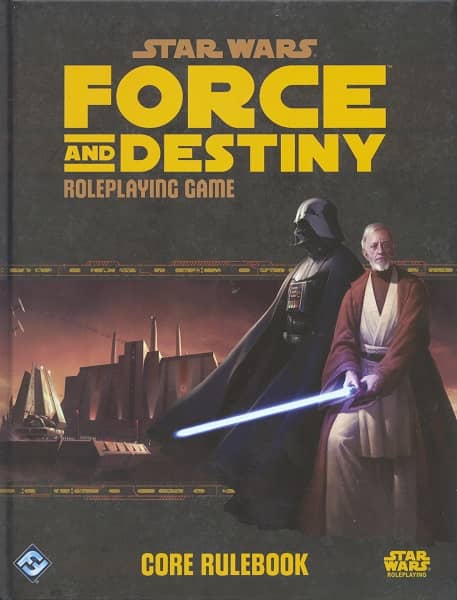

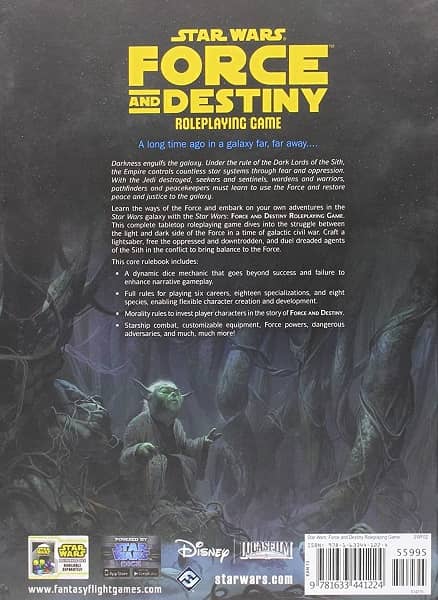

Dungeons & Dragons, Star Wars: Force and Destiny, and others use a process whereby you select a species (if applicable), select a career, apply a number of adjustments to the basic character template, and then make choices about talents and specializations and skill choices. The names may vary (class, feats, etc.), but the basic principles remain. For example, in Force and Destiny from the core rulebook, players choose from one of eight species. These have default attribute score adjustments and some level of unique trait or ability (breathing underwater for Nautolans for example). Players then choose from one of four careers and then choose from one of three specializations in that career. One of the narrative or logical challenges with this construct is that if you want to play a 40-year old human smuggler, you may have the exact set of skill points, etc., as other players, who may have a 20-year old bounty hunter just making her mark on the world. Truth be told, this is not a significant challenge, but one nonetheless. Particularly in class-based systems. My 40-year old cleric is at level one — the same as that 20-year old barbarian.

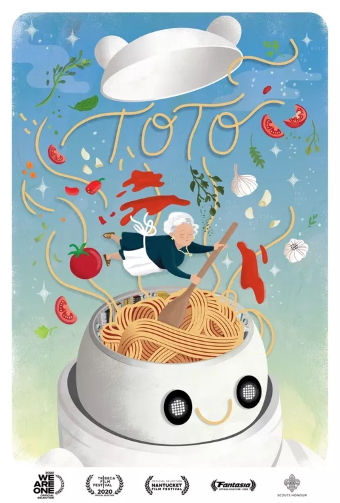

Watching a film festival at home instead of in theatres raises a question that’s become a much-debated point over the last couple of years: is the experience of viewing a movie on a TV screen essentially different and essentially lesser than watching the same movie in a theatre? I don’t think there’s a single answer to this question. Different movies and different viewers and different circumstances will create better or worse scenarios. I think it is probably safe to say that the theatrical experience has much more sensory power; that the powerful sound system and the controlled environment and the full dark of a theatre will usually be more immediately overwhelming to a viewer. But it’s reasonable to wonder if a movie that relies on sheer sensory power can be called ‘a good movie.’

Watching a film festival at home instead of in theatres raises a question that’s become a much-debated point over the last couple of years: is the experience of viewing a movie on a TV screen essentially different and essentially lesser than watching the same movie in a theatre? I don’t think there’s a single answer to this question. Different movies and different viewers and different circumstances will create better or worse scenarios. I think it is probably safe to say that the theatrical experience has much more sensory power; that the powerful sound system and the controlled environment and the full dark of a theatre will usually be more immediately overwhelming to a viewer. But it’s reasonable to wonder if a movie that relies on sheer sensory power can be called ‘a good movie.’

Miyamoto Musashi (1584-1645) was one of the greatest samurai and greatest swordfighters ever to live. By his own account, he fought over sixty duels and won all of them. Stories about Musashi have been told and retold over the centuries, notably including the great novel Musashi (1935-39) by Eiji Yoshikawa. Films about him have proliferated, the most famous likely being Hirohi Inagaki’s Samurai trilogy (1954-55) starring Toshiro Mifune as Musashi.

Miyamoto Musashi (1584-1645) was one of the greatest samurai and greatest swordfighters ever to live. By his own account, he fought over sixty duels and won all of them. Stories about Musashi have been told and retold over the centuries, notably including the great novel Musashi (1935-39) by Eiji Yoshikawa. Films about him have proliferated, the most famous likely being Hirohi Inagaki’s Samurai trilogy (1954-55) starring Toshiro Mifune as Musashi.

The chain of inspiration behind a work of art can be stunning to behold. Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffman was a musician, critic, and fiction writer in the early nineteenth century whose surreal and gemlike short stories are wonders of early fantasy. Some of those stories were worked into the libretto of Jacques Offenbach’s 1881 opera Les contes d’Hoffmann. Adapted to films at least three times, most notably by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger in 1951, Offenbach’s work would inspire the great manga creator Osamu Tezuka in 1973. A

The chain of inspiration behind a work of art can be stunning to behold. Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffman was a musician, critic, and fiction writer in the early nineteenth century whose surreal and gemlike short stories are wonders of early fantasy. Some of those stories were worked into the libretto of Jacques Offenbach’s 1881 opera Les contes d’Hoffmann. Adapted to films at least three times, most notably by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger in 1951, Offenbach’s work would inspire the great manga creator Osamu Tezuka in 1973. A

Day 6 of Fantasia 2020 started for me with a panel on folk horror. While you can find the

Day 6 of Fantasia 2020 started for me with a panel on folk horror. While you can find the