Art Evolution 1: Jeff Laubenstein

I’m a gamer, a lifer, someone who at the age of thirty-nine doesn’t get to roll dice like it did at nineteen, but I still take a week’s vacation every year to hang out with High School friends and revisit campaigns where characters have been on paper long enough to legally drink in the U.S.

I’m a gamer, a lifer, someone who at the age of thirty-nine doesn’t get to roll dice like it did at nineteen, but I still take a week’s vacation every year to hang out with High School friends and revisit campaigns where characters have been on paper long enough to legally drink in the U.S.

My love for fantasy role-playing goes back to middle school. There, I was introduced to Dungeon’s & Dragons, but it wasn’t just the concept that inspired my love affair, it was the art. The first piece of fantasy role-playing art I ever saw was the module A2: Secrets of the Slavers Stockade.

I stared at it for a full hour in History class; flipped through the pages trying to figure out why the cover wasn’t stapled on, and went home convinced this was something I had to get involved in.

Enter the Sears Christmas catalogue and TSR’s D&D Basic Edition red boxed set. Once I saw Larry Elmore’s red dragon and seemingly endless treasure trove, I convinced my mother to order it and began a journey lasting nearly thirty years.

I still buy gaming supplements for art alone, collecting entire genres and systems knowing full well I will never have the time to play them. If you put a great cover on it there’s a good chance I’ll buy, and I devour new talent almost as fast as I’ll snap up a collector’s piece from the seventies or eighties on eBay.

British science fiction author Edwin Charles (“E.C.”) Tubb died on September 10, 2010, at his home in London, England. He was 90 years old.

British science fiction author Edwin Charles (“E.C.”) Tubb died on September 10, 2010, at his home in London, England. He was 90 years old. Star Soldier by Vaughn Heppner, Book #1 of the Doom Star Series, has reached the Top of Amazon’s bestseller list for

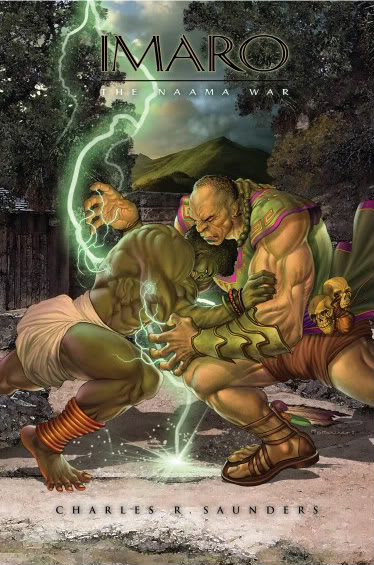

Star Soldier by Vaughn Heppner, Book #1 of the Doom Star Series, has reached the Top of Amazon’s bestseller list for  Imaro: The Naama War

Imaro: The Naama War Jack the Giant Killer, by Charles de Lint

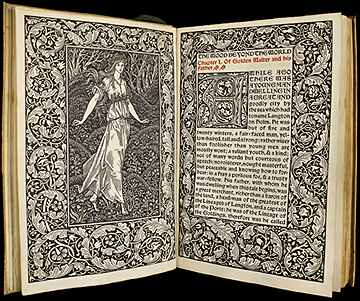

Jack the Giant Killer, by Charles de Lint This is the third in a series of posts looking at the question of who wrote the first otherworld fantasy: that is, the first fantasy to be set entirely in its own fictional world, with no connection to conventional reality at all. It’s an innovation traditionally ascribed to William Morris, but I think I’ve found an earlier writer who deserves that honor.

This is the third in a series of posts looking at the question of who wrote the first otherworld fantasy: that is, the first fantasy to be set entirely in its own fictional world, with no connection to conventional reality at all. It’s an innovation traditionally ascribed to William Morris, but I think I’ve found an earlier writer who deserves that honor. On June 24, Science Fiction author and critic F. Gwynplaine “Froggy” MacIntyre posted

On June 24, Science Fiction author and critic F. Gwynplaine “Froggy” MacIntyre posted  The August issue of Locus, the Magazine of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Field, contains a review of our

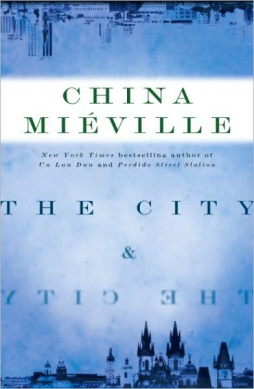

The August issue of Locus, the Magazine of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Field, contains a review of our  The City and the City

The City and the City