Charles de Lint and The Little Country

In talking about portal fantasies last time, I was moved to reread one of the more unusual examples of the sub-genre, Charles de Lint’s The Little Country (1991).

In talking about portal fantasies last time, I was moved to reread one of the more unusual examples of the sub-genre, Charles de Lint’s The Little Country (1991).

The book is in a very real sense two books, but it isn’t a simple play-within-a-play, story-within-a-story thing: Each book is being read by the protagonist of the other. The now-overused self-referential concept known as “meta” wasn’t so common when The Little Country was written, but it might have been invented to describe the novel. The book is extremely self-aware, something which even the protagonists are forced to recognize.

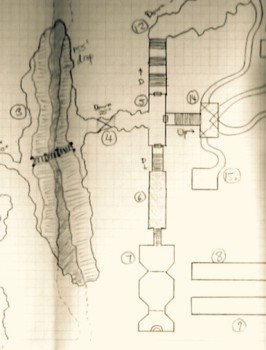

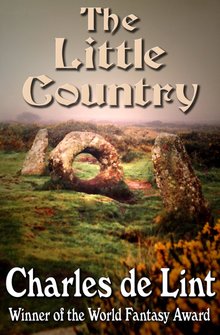

The two stories do run parallel to one another, but this isn’t a case of success in one world reflecting or depending on success in the other world, as we see in King and Straub’s The Talisman, for example. The characters don’t overlap, the settings aren’t the same, though you might say that the outcomes are. There is a physical object common to both worlds, a standing stone with an opening through which objects and people can pass. Both worlds have the tradition that passing through the stone nine times at moonrise effects some magical change – entrance into the land of the faerie, a cure for sickness or barrenness, etc.

In the thread which most resembles our world, Janey Little, a twenty-something traditional musician, finds a book in her grandfather’s attic – a one-of-a-kind hitherto unknown work left in her grandfather’s keeping by the author, an old and eccentric friend. The book is called “The Little Country.”