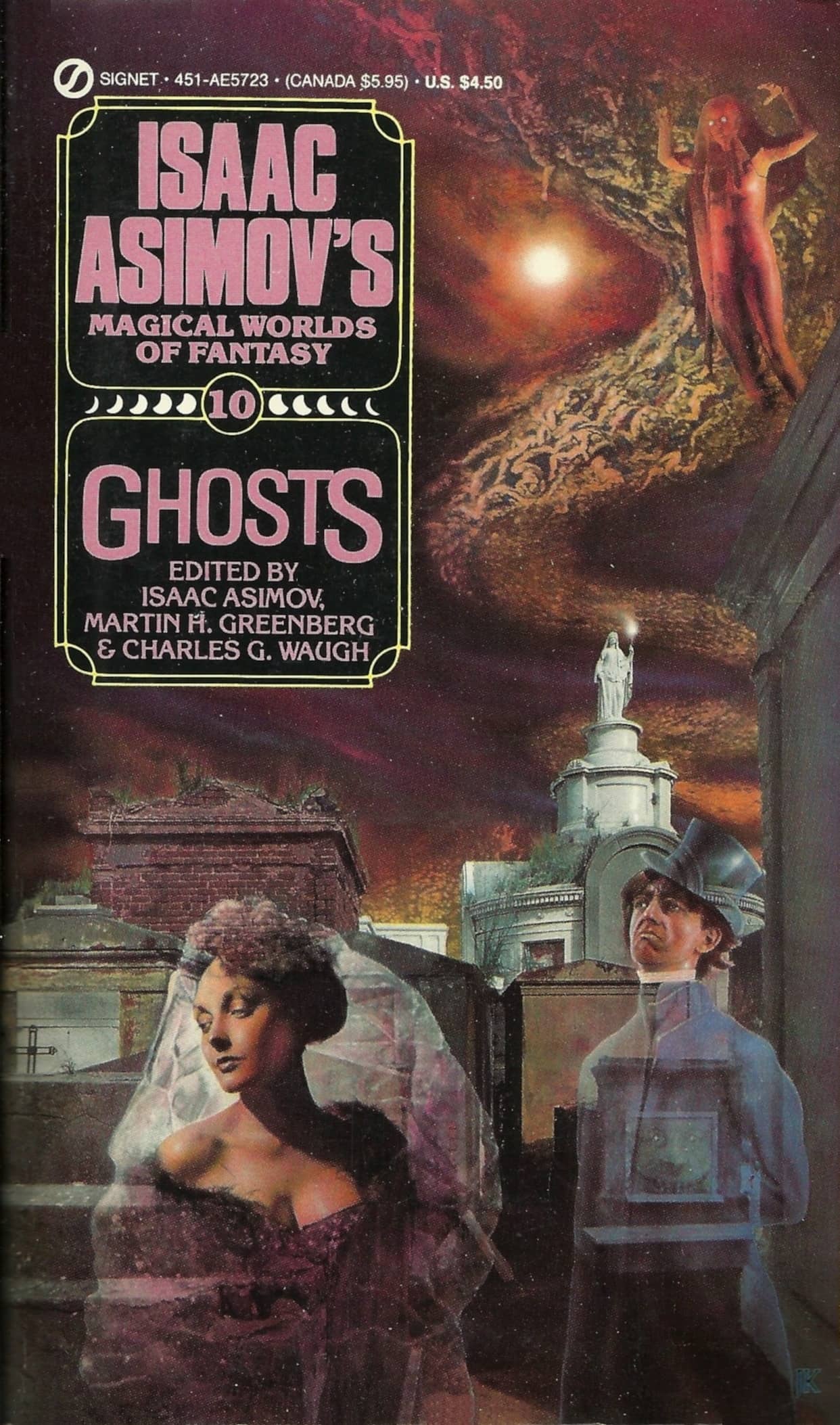

Vintage Treasures: Isaac Asimov’s Magical Worlds of Fantasy 10: Ghosts edited by Isaac Asimov, Martin H. Greenberg, and Charles G. Waugh

|

|

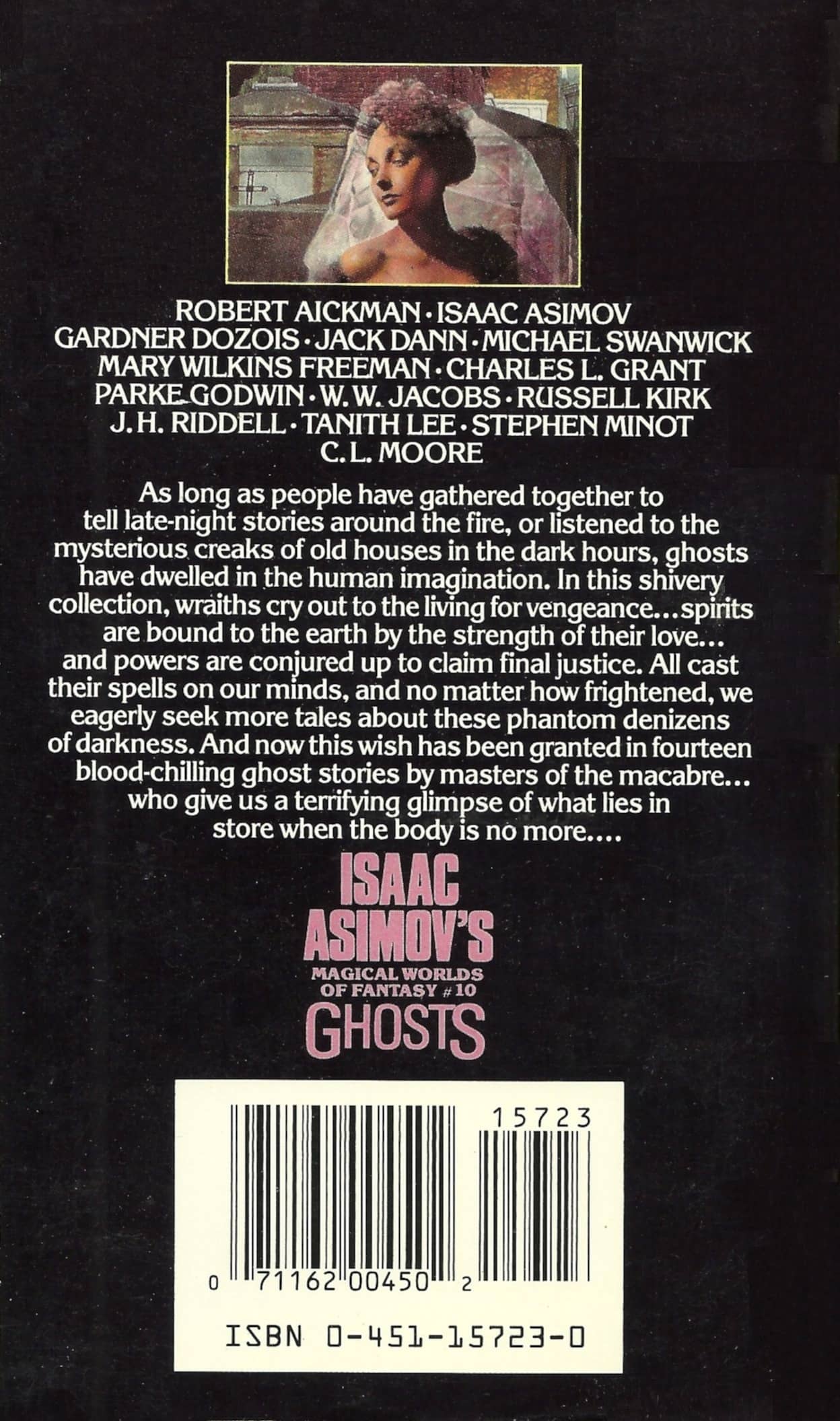

Isaac Asimov’s Magical Worlds of Fantasy 10: Ghosts (Signet/New American Library, 1988). Cover by J. K. Potter

Isaac Asimov had a lot of gifts. He was a world famous polymath, a marvelous science explainer and popularizer, and a pretty darned skilled writer of science fiction. But he doesn’t get a lot of credit for one of his greatest talents, a skill in short supply even today: The man knew how to sell anthologies.

After some of his early SF anthologies became enduring top-sellers, often remaining in print for decades (including The Hugo Winners, Volume I and II, Before the Golden Age, and Where Do We Go From Here), publishers discovered that the name Isaac Asimov on the cover of an anthology almost guaranteed it would sell.

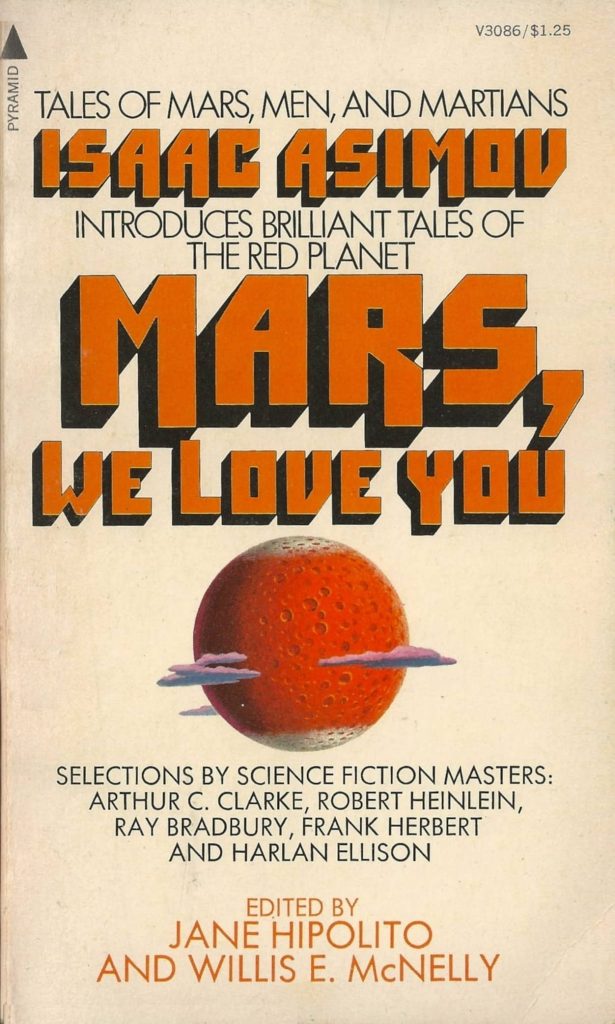

Asimov exploited this heavily for the remainder of his career, lending his fame to many important anthology series, often co-created with frequent collaborators Martin H. Greenberg and Charles G. Waugh. These include The Great Science Fiction Stories (25 volumes in 23 years), Isaac Asimov’s Wonderful Worlds of Science Fiction (10 volumes in 8 years), and Isaac Asimov’s Wonderful Worlds of Fantasy (12 volumes in 9 years). It’s that last one we’re going to look at today, with one of the final volumes: Ghosts, published by Signet in 1988.