Vintage Treasures: Swords Against Darkness edited by Andrew J. Offutt

|

|

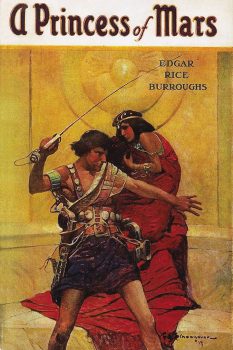

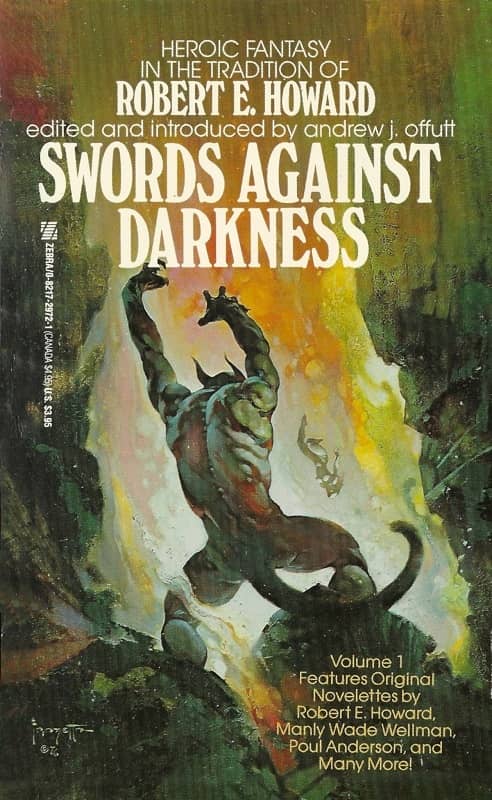

Swords Against Darkness (Zebra Books, February 1977). Cover by Frank Frazetta

Sword Against Darkness was a seminal five-volume sword & sorcery anthology series edited by Andrew J. Offutt in the late seventies (1977-79). It published original fantasy by some of the biggest names of the era, including Andre Norton, Tanith Lee, Keith Taylor, Charles de Lint, Charles R. Saunders, Orson Scott Card, Simon R. Green, David C. Smith, Robert E. Vardeman, Darrell Schweitzer, Diana L. Paxson, and many others.

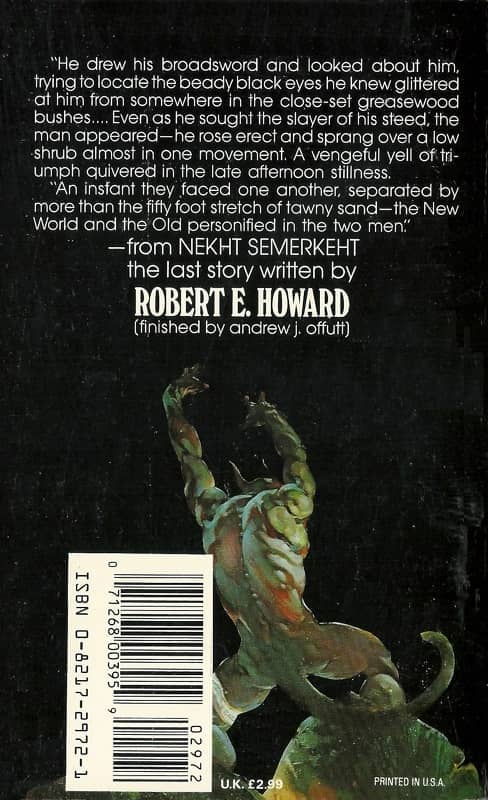

The first volume appeared in early 1977, and it was one of the strongest original fantasy anthologies of the decade, packed full of tales of the haunted Roman frontier, a plague of giants, the wily goddess of Chance, the last survivor of Atlantis, Lovecraftian horrors, scheming demons, resourceful rogues facing evil spirits, and much more. It included a Simon of Gitta novelette by Richard L. Tierney, a powerful Robert E. Howard fragment completed by Andrew J. Offutt, plus Poul Anderson, Manly Wade Wellman, David Drake, Ramsey Campbell, and many others.