Incredible, In More Ways than One: Richard Matheson’s The Shrinking Man

The Shrinking Man by Richard Matheson

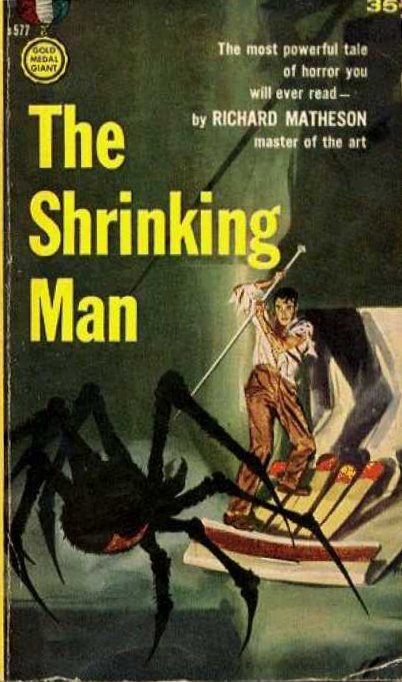

First Edition: Fawcett Gold Medal, May 1956. Cover art MH.

The Shrinking Man

by Richard Matheson

Fawcett Gold Medal (192 pages, $0.35, Paperback, May 1956)

Cover art MH

I think it safe to say that Richard Matheson is best remembered today for his novels and stories that were adapted into films and TV scripts, including the dozen plus scripts he himself wrote for Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone TV series in the late 1950 to early ‘60s. (An ironic exception is Matheson’s first-published short story, “Born of Man and Woman” (1950), which remains in print in the first volume of The Science Fiction Hall of Fame.)

Matheson’s first six novels, at least, from I Am Legend (1954) to What Dreams May Come (1978), were all adapted into films. (Among short stories adapted into film was 1971’s “Duel,” which became a TV movie under Steven Spielberg’s direction). The earliest film adaptation came from his second novel, The Shrinking Man (1956), becoming the striking if dubiously plausible 1957 film dubbed, Hollywood-style, The Incredible Shrinking Man. I suspect more people have seen the film than have read Matheson’s novel. Yet while I’m reviewing the book here and not the film (which I last saw decades ago), I will compare the two on a few points, mainly because Matheson himself wrote the screenplay for the film. So the differences between novel and film may be instructive.

I was not a fan of the movie when I watched it years ago; it seemed obviously implausible, scientifically, and I was put off by the pious Hollywood ending that, as in other sf films of the time (e.g. The War of the Worlds), concludes that, despite all the trauma and death, everything is fine for the survivors because God. In fact, that the novel did not end precisely that way is one reason to consider and compare the two versions of this story.

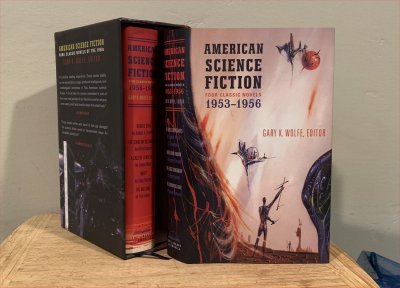

(I’m rereading the novel now mainly to revisit all nine novels in the Library of America set of 1950’s SF novels, photo below.)

Both the novel and the film excel in considering, given their premise, how it plays out for our protagonist. On this point the film is superior to the novel. The film shows us the shrinking man and especially the cellar environment he finds himself trapped in, complete with giant black widow spider. There’s almost a sense of play, in seeing how the director and production staff create gigantic props to represent ordinary items from the perspective of the shrinking man (rather as the Irwin Allen 1960s TV series Land of the Giants did). The narrative description in the novel is necessarily less striking and, frankly, as I read it, got to be tedious.

The principal difference between the novel and film is that the film proceeds in chronological order, while the book alternates chapters about our hero trapped in the cellar with flashback scenes describing how he began to shrink and the problems he encountered as he did.

Gist

A man affected by radiation (in the 1950s) begins to shrink, steadily, affecting his relationship with his wife and family, and ultimately trapping him in a cellar, where at the height of an inch he struggles for food and water and battles a (to him) gigantic black widow spider.

Take

The premise might be implausible, but the parallel stories of survival in a cellar and loss of identity as a husband and father are dramatic and memorable.

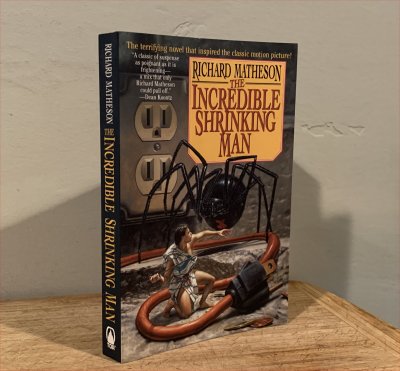

The Incredible Shrinking Man

by Richard Matheson

Tor (351 pages, $14.95, Trade Paperback, February 2001)

(This is an omnibus of the novel, over 204 pages, and nine short stories.)

Cover art Donato

Summary and [[ Comments ]]

The book alternates chapters, and partial chapters, with descriptions of the shrinking protagonist’s current plight, with the story of how he got to where he is. I’m going to summarize the book’s plot along these two threads, rather than track all 17 chapters in order. Page references are to the Tor trade paperback shown above.

Scott Carey stuck in the cellar

- In the present (of the book’s 1956 writing), a man named Scott Carey and his brother Marty are on a boat in the ocean, when a shimmering tidal-like wave passes over the boat, a wave we learn later is a mixture of radiation and insecticides. [[ Radiation was, of course, to the go-go bugaboo in the 1950s; in other films, it made things gigantic, as in the 1954 movie Them! ]]

- After this flashback, the novel returns to the “present,” as we get a description of Carey as he flees a gigantic spider (with “stalk like” legs), runs past tank-size cans smeared with green, red, and yellow, and coming to a cliff, jumps from it to an orange ledge, then reaches the floor of a canyon, and hears a thunderous flame in a steel tower going out.

- After 3 ½ pages of this, Matheson reveals that our hero is not on some pulp-fiction planet with gigantic spiders — rather, he’s a tiny man in an ordinary cellar. It’s an ordinary black widow spider. The tank-sized cans are paint cans, smeared with colors of paint. The steel tower is a water heater. There’s also a garden hose (perceived as a serpent), a stack of lawn chairs, a croquet set. Our miniature man is trapped there.

- As a set-up, this is dramatically very effective. Immediately the reader wants to know: how did this man become only an inch tall? Why is he trapped — alone — in a cellar? And will he survive the giant spider? In fact, Scott Carey reflects that he’s in his last week; he’s shrinking by 1/7 inch a day. In a week he’ll be gone. So: what will happen when he shrinks to nothing? This question is not answered until the very end (and then dubiously).

- Alternating chapters of the novel proceed with Scott Carey’s situation. His bed is a sponge and a handkerchief. He’s trapped in a cellar, where he uses a thimble to collect water to drink. He climbs, like a mountain-climber, to the top of a refrigerator, to find a box of crackers to eat. The crackers are ruined, water-logged, moldy. He finds some dry crumbs, wraps them up, and pushes them down over the cliff onto the floor. The water heater leaks.

- Throughout this Carey has doubts. Why try to survive? In a few days he’ll disappear. Yet he goes on.

- A “giant” – his wife Louise – enters the cellar, not seeing him, to fix the water heater. He is too tiny for his cries to be heard. A cat appears, threatening him.

- And so on. As I said, this gets tedious; the abstract descriptions, as in the second chapter, get more explicit but not necessarily any clearer. Carey’s various attempts to climb, for example, rely on descriptions of climbing equipment, or details of how he climbs (there was something about filigree on a refrigerator), that weren’t apparently clear, from this reader’s 2021 perspective.

Flashbacks

The dramatic interest of the book (as opposed to the thriller survivor aspect) is the story of what happens to Scott Carey, how he discovers he’s shrinking, and how he deals with this over many months. So here are, in the novel, the flashbacks:

- He began as a six-foot tall man. After the exposure to the radiation cloud, he realizes, a couple months later, that he has gotten shorter. There are intermediate sub-chapters headed by his height in inches.

- At 68”, Carey tells his wife. He suspected it a month before, and saw Dr. Branson, who explained that Carey is losing weight and height proportionately. His wife Lou (Louise) is shocked, at first denying that it’s possible, then insisting that he see a specialist. But he is worried about the cost. Scott has already borrowed $500 from his brother Marty for the tests he’s already had done. His career plans are already disrupted.; he has no income. [[ Obviously he has no kind of health insurance… ]]

- At 64”, he has been to a Center in New York, for tests, but he has left before the tests were finished; he felt like a toy for the doctors to play with, and they haven’t found anything (and he can’t afford more treatment). Lou picks him up. They are tense.

- At 63”, He visits his mother. Boys in the street treat him like a kid. He spends an hour with his mother, talking about anything but. Except that she’s sure the doctors will find a cure. And then he gets a notice from the Center that the doctors will continue his treatment for free.

- At 49”, after a year of this, he comes out from a shower one evening and tries to cuddle with his wife. Yet she talks, and treats him, like a boy. – This is a very dramatic scene, underplayed, with dialogue suggesting things the two cannot fully express. He tries to kiss her, and she is shocked. He asks, doesn’t she know? He suggests she call her parents, to make arrangement for… when he’s gone. She’s angry he suggested it. They go to bed, and when she realizes that he’s taken his wedding ring off his finger, but keeps it on a chain around his neck, she throws herself upon him and they make love.

- His situation goes public, and he gets offers from magazines for his exclusive story, or photos. He refuses a first offer. Later a photographer comes to the apartment, but poses him in his adult clothes, making him look ridiculous. As his story gets out, he gets mail, from religious fanatics, and obscene letters from both women, and men. Meanwhile he’s working for his bother Marty, until the office situation gets too awkward, and Marty tells him to stay home, though Marty will still send him checks.

- At 42”, Scott is driving home, has a tire blow out, is too small to change the tire, and walks toward the nearest town to find help. He’s picked up by a lecherous man, who thinks Scott is a boy, and who babbles in literary references and in French, who puts his hand on Scott’s leg, until Scott can escape and flee.

- At 35”, Scott finds Lou’s drinking and swallowing sounds noisy and disgusting. He goes for a walk, down to the lake, near where they moved six weeks before. He’s angry about their situation, about how his daughter Beth has withdrawn from him, no longer thinking him an authority figure. His brother has lost a contract and no longer has the funds to keep sending him checks. His sex drive is still strong. And then, by the lake, three teenaged boys decide to pester him, taunting him, until they realize who he is, and call him “freako.” He flees down an alley, climbs over a fence, and hides in a cellar. (But a cellar with a dirt floor, not the cellar he later gets trapped in.)

- He recalls the medical center’s latest findings: he has a negative nitrogen balance. The doctors find a toxin, and ask if he was exposed to any kind of germ spray? Scott recalls a city truck spraying trees… and then the boat incident, insect spray contaminated by radiation. Since then the doctors have been searching for an antitoxin. Every day Scott checks the mail, expecting their response, but gets nothing.

- At 21”, Lou gets a job at the grocery store, and they hire a neighbor girl to take care of Beth. Scott hides in the basement while she’s there each day. He imagines what she must look like. [[ I note that Nabokov’s novel Lolita was published the year before Matheson’s. ]] Inevitably, thinking she’s alone in the house, the babysitter explores, and eventually explores the cellar; he hides, but she sees his plate of sandwiches and knows something’s odd. She doesn’t seem him, but she takes his sandwiches. Later, he watches her lying on the grass outside, through the cellar windows. He takes to climbing outside of the cellar and walking around to the front of the house to spy on the girl through a front window. But one day he slips, makes a noise, and she sees him. (And is subsequently fired.)

- [[ Throughout, Matheson is fairly explicit about Scott’s sexual needs, and his sense of a loss of masculinity as his wife and daughter fall away from him. In this section, Matheson’s wording tells you all you need to know. Scott, watching the girl, is “rigidly tensed” (page 128.3); later as he thinks of her at night, “Sleep grew turgid with dreams of Catherine…” page 135b. ]]

- At 18”, he attends a carnival with wife Lou and daughter Beth. They tell him to stay in the car, but he does not. He discovers a trailer where a tiny woman lives, a carnival performer dubbed Mrs. Tom Thumb. They are attracted to each other, desperately, and kiss. She dresses and leaves for another performance, and Scott returns to his wife and tells her he’s met someone and has to stay, for just this night. And Lou, after initial anger, agrees to let him spend the night. Later, in the cellar at 2/7” tall, he recalls that night with Clarice, how he was still a man.

- He recalls after these events determining to write his story, using pencils until they grow too large to handle. He doesn’t tell Lou at first, but she finds out, types of his pages, and submits them to publishers. He gets a deal, grateful that he has provided security for Lou.

- At 10” Louise brings home a giant dollhouse, with furniture. His book is selling. The last chapter of his book was “Life in a Dollhouse.” The furniture is fake, of course, with no padding, until Lou fashions some. Beth brings him a doll, as a companion to sleep next to.

- At 7”, his daughter Beth picks him up like a doll and he screams to be let down. Then the kitchen door blows open, as it’s snowing outside. Scott goes to close it, but the cat threatens him, and he is blown through the door, and becomes trapped outside. He lurches through the snow toward the front steps. A sparrow attacks him relentlessly, and he escapes it through a missing pane of the cellar window. He’s trapped and can’t get out. Ten minutes later he hears Lou and Beth outside, shuffling through snow, calling his name. Of course they don’t find him.

Back to the finale

- As he nears the end, Scott becomes determined to kill the spider. He had stabbed it once before but it survived. Now killing it is symbolic somehow of his indomitable will to live. He’s too small to stab it, but he decides he can build a pit, in the sand along the edge of the cellar, plant a pin at the bottom, sticking up, and lure the spider toward it… He hasn’t seen the spider in a couple days, then notices a partially eaten beetle in its web. He throws rocks (bits of sand) at it, until it climbs down from its web, and chases toward him. It falls into the pit, and Scott slides a piece of cardboard over the pit to trap it. …But its legs appear underneath the cardboard, and it crawls out, trying to shake away the pin it got stabbed on. Scott plunges another pin into it, and finally it dies. [[ A conventional two-times-fail third-time-win suspense scene, but well told. ]]

- Later he hears steps. A giant comes in, tossing cartons onto the floor, then Lou’s suitcase. It’s Marty, Scott realizes, and Beth is there asking to help, and Scott realizes they’re moving out. He screams at them, but they don’t hear. He tries jumping on Marty’s shoe, and is tossed away; tries hooking Marty’s pant cuff, to climb into it, but again is torn away. He realizes he can never attract their attention.

- The house empty, Scott now just one-seventh an inch tall, he looks around and sees that he has a chance to escape the cellar after all. Marty has left a long pole leaning against the wall, at a shallow angle; he can easily climb it. Above that is the dead spider’s web, which he can climb.

- Scott gets mystical. Maybe things are working out as planned? Is there a purpose to his survival? Was it merely chance that the pole was thrown there by his brother? Everything seems suddenly meaningful.

- He climbs the spider web, to the shelf by the cellar window. Blinding light. He climbs over the window sill, then down to the ground, crosses the cement walk, and stands at the edge of the world.

- He lies on his back looking at the stars. He feels no terror. He’s content. He’s fought a good fight.

And in the end…

- Scott wakes the next morning, even through he presumably should have shrunk from 1/7” to nothing. Where is he? He sees patches of blue through leaves.

- How can he be less than nothing? He has an idea: maybe as there is a universe without, there is also a universe within. Microscopic worlds. To a man, zero means nothing. But not in nature. There’s no point of non-existence in the universe. So perhaps also with intelligence—there might be others here, in this new world he’s discovered. He runs toward the light, looks at his new world, a wonderland. The end.

American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s

edited by Gary K. Wolfe

Library of America (1672 pages, $14.95, Boxed Hardcover set, October 2012)

(Omnibus of nine novels, including The Shrinking Man by Richard Matheson.)

Jacket and Box Illustrations Richard M. Powers

Comments

Incidental ones first.

- Why is the spider chasing him? Don’t spiders generally sit on, or by, their webs, waiting for an insect to get snagged in it? Of course the chase scenes between spider and man are the exciting action scenes, in both book and film, so presumably the author expects us to grant some artistic license.

- At least twice Scott and his wife worry about the expense of buying new winter clothes. Why was there a need to buy such clothes every year?

More substantially, as I sat down to read this book again (decades after last reading it, or seeing the film), I posed in my mind issues I wanted to see how were addressed.

- Is there any attempt to explain why this shrinking happens, except for the radiation/insecticide bugaboo? Answer on this reading: No. There’s some doubletalk about nitrogen fixation that causes him to lose body mass, but that might more plausibly result in shrinkage, like starvation, of an ordinary sized man.

- To what extent does the novel deal with true matters of scale, how a tiny man would interact with the world around him?

What it does address:

- Ordinary sounds become very loud to Scott Carey—the sound of the water pump, even his wife’s voice. From the dollhouse, he uses a small microphone to talk to his wife.

- Scott becomes so small he realizes he can jump or fall long heights without being hurt, like an ant.

What it does not address:

- Surface tension, as when Scott Carey drinks water, even the tiny drops in the end of a garden hose, when he’s a seventh of an inch tall. (Recall James Blish’s “Surface Tension,” about a tiny race of humanoids who struggled to break the surface tension of their water world, in order to reach the land above.)

- How a miniature man could digest pieces of a full-sized slice of bread. Are the atom and molecular sizes comparable?

- The general issue of how he is shrinking. By his last week in the cellar, via an upright ruler, Scott Carey realizes he’s shrinking 1/7 of an inch a day. That’s a linear measure. More plausibly he’d be shrinking proportionately, say, 2% of body mass a day. Had the shrinking been described like that, no issue of disappearing completely would have arisen.

Finale

The end of the book, compared to the ending of the film.

The book (which I’ve typed out):

Then he thought: If nature existed on endless levels, so also might intelligence.

He might not have to be alone.

Suddenly he began running toward the light.

And, when he’d reached it, he stood in speechless awe looking at the new world with its vivid splashes of vegetation, its scintillant hills, its towering trees, its sky of shifting hues, as thought the sunlight were being filtered through moving layers of pastel glass.

It was wonderland.

There was much to be done and more to be thought about. His brain was teeming with questions and ideas and — yes — hope again. There was food to be found, water, clothing, shelter. And most important, life. Who knew? It might be, it just might be there.

Scott Carey ran into his new world, searching.

The film (copied from IMBb), last lines, with some para breaks added:

I was continuing to shrink, to become… what? The infinitesimal? What was I? Still a human being? Or was I the man of the future?

If there were other bursts of radiation, other clouds drifting across seas and continents, would other beings follow me into this vast new world? So close — the infinitesimal and the infinite.

But suddenly, I knew they were really the two ends of the same concept. The unbelievably small and the unbelievably vast eventually meet — like the closing of a gigantic circle.

I looked up, as if somehow I would grasp the heavens. The universe, worlds beyond number, God’s silver tapestry spread across the night.

And in that moment, I knew the answer to the riddle of the infinite. I had thought in terms of man’s own limited dimension. I had presumed upon nature. That existence begins and ends is man’s conception, not nature’s.

And I felt my body dwindling, melting, becoming nothing. My fears melted away. And in their place came acceptance. All this vast majesty of creation, it had to mean something. And then I meant something, too. Yes, smaller than the smallest, I meant something, too. To God, there is no zero. I still exist!

Science fiction is about surviving to discover new worlds, but Hollywood producers of the 1950s, apparently, needed to reassure their audiences that such cataclysms and discoveries did not threaten the beneficence of their God.

Mark R. Kelly’s last review for us was of Robert Silverberg’s Up the Line. Mark wrote short fiction reviews for Locus Magazine from 1987 to 2001, and is the founder of the Locus Online website, for which he won a Hugo Award in 2002. He established the Science Fiction Awards Database at sfadb.com. He is a retired aerospace software engineer who lived for decades in Southern California before moving to the Bay Area in 2015. Find more of his thoughts at Views from Crestmont Drive, which has this index of Black Gate reviews posted so far.

I read the book as a kid and found it rather tedious even then.

Decades later I read “I Am Legend” and thought it was brilliant.

Some years later “Shrinkin Man” was on my reading list and I realized I had read it before. Alas, I still think it’s rather tedious and a huge disappointment after “I Am Legend”. One problem is that it to a certain degree fails the suspension of disbelief test for me.

I actually enjoyed the movie more.

And I think it was always meant to be a movie. Hollywood was obsessed with “Monsters”, especially giant insects, back then. And that’s what Science Fiction meant to Hollywood.

I read this when I was a kid (I had the original Gold Medal edition pictured here – I wish I still had it!) and again several years ago, and got a reasonable amount of enjoyment out of it both times. Of course it’s scientifically absurd (if I remember rightly, Damon Knight knocked the superior I Am Legend for the same reason) but if airtight science is what you’re looking for, you don’t read books with covers that show a guy battling a black widow with a stickpin in the first place. In the end, it’s not a book about any kind of plausible scientific situation, it’s a book about a man alone in an extraordinary predicament, struggling against incredible odds – a novel of outlandish adventure, in other words. On that level, it works just fine.

I never read the story, but bought the film on dvd around ten years ago. I actually thought it was pretty good. I guess it makes more sense structurally for the story (when written) to be told in a series of flashbacks – otherwise it would be very linear; it’s just about a guy who keeps getting smaller and smaller. At least the flashbacks establish a current predicament (the spider) and some intrigue as to how the character ended up in that predicament.

This might have worked in the film too, but I don’t think it was necessary. Sometimes films can follow very simple narrative structures but still manage to be compelling, maybe because when you’re watching a film, you’re very much inhabiting the moment. I think the film had a good forward momentum and (like a lot of films produced around then) it had the courage of its convictions; the mc wasn’t going to stop growing smaller, with all that entailed. I think the final voice-over established the right amount of ambiguity – the viewer knows the mc is screwed (crucially because wherever he’s going, he’ll be alone) and takes the mc’s belief that he’s going to some better place with a very large grain of salt. This is a guy trying to convince himself that things will be OK, despite all appearances to the contrary. Or at least, that was my interpretation of it.

Reading your article, I was struck by the similarities to ‘The Metamorphosis’, specifically in how the attitude of others – family members etc – undergo a transition as the mc becomes smaller.

What an excellent analysis of one of my favorite novel/film combinations! By the way, Matheson’s original screenplay maintained the book’s flashback structure; it was the studio that insisted on the reshuffling. Matheson himself always preferred the original structure. So do I, but it’s still one of the great ‘50s SF films.

Nice comment. I shall have to reread Metamorphosis…

Actually it was a repairman in the book who shows up to fix the water heater while Scott’s brother shuts off the water, in film version.

I enjoyed both film and book.Why did they keep the cat, who is still around when Scott is 7″ tall? In film, it’s described as a former pet.Maybe given to a neighbor. The

book has the cat encounter when Scott is about half an inch tall.

Film special effects great for their day.Could be remade and maybe done well…like the effects in Ant Man.