Birthday Reviews: Joe Patrouch’s “The Attenuated Man”

Joseph F. Patrouch, Jr. was born on May 23, 1935.

Patrouch was a teacher in Ohio who had a brief career writing science fiction. In the early 1970s, he wrote several essays about Asimov’s fiction and published his first short story, “One Little Room an Everywhere” in the February 1974 issue of Vertex. Most of his fiction has never been reprinted, with the exceptions “The Man Who Murdered Television” and “Legal Rights for Germs.” He also published The Science Fiction of Isaac Asimov in 1974.

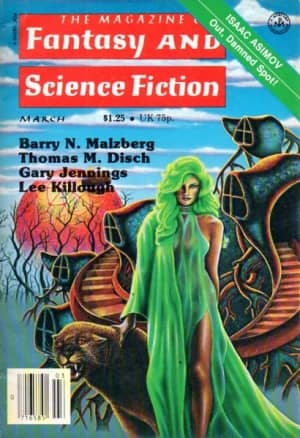

“The Attenuated Man” was published by Edward L. Ferman in the March 1979 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. It has never been reprinted.

Ken Hamilton sneaks into his father’s company to use the Transmat machine to become the first man on Mars, in an attempt to prove to his father than he isn’t completely worthless. Unfortunately, things go wrong for him almost immediately as he starts bleeding from his eyes, ears, and mouth. Back on Earth, Ken’s excursion has been discovered and his father’s staff is trying to figure out how to get him back, especially once they realize something has gone wrong and they can’t send someone after him without the same problems occurring.

Patrouch has an interesting look at some of the dangers of teleportation, although the impact seems to be different when transmatting people to different places, a discrepancy which he discusses in the story. Furthermore, although he indicates that Hamilton has a very low opinion of his son’s intelligence and abilities, the son figures out part of the solution that will allow him to return to Earth safely, and understands what has happened to him.