Adventure in the Final Days of Civilization in the British Isles: The Trials of Koli by M.R. Carey

|

|

|

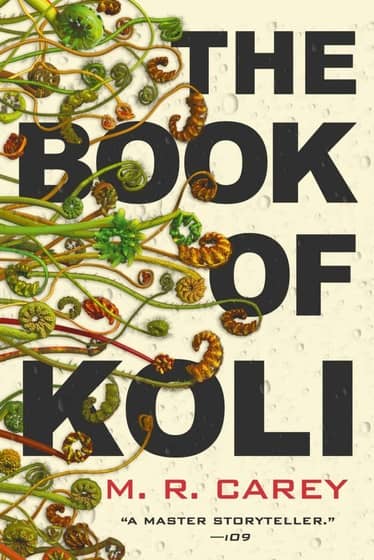

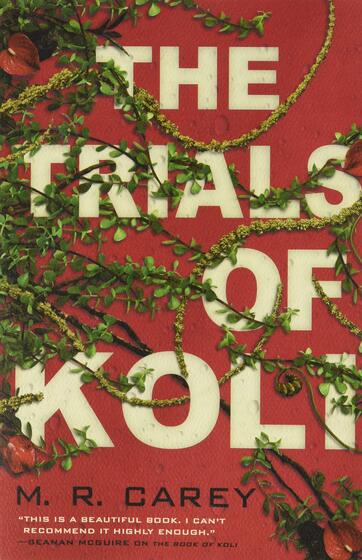

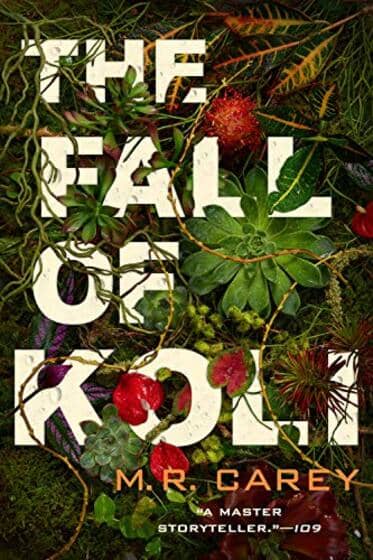

The Rampart Trilogy by M.R. Carey, all published by Orbit: The Book of Koli (April 2020),

The Trials of Koli (September 2020), and the forthcoming The Fall of Koli (March 2021). Cover designs by Lisa Marie Pompilio

Post-apocalyptic reading doesn’t seem the best thing for these times of global pandemic and a presidential term that’s seen the US move backward on almost every progressive climate policy. And yet as I explained in my review of The Book of Koli, M. R. Carey has managed to create an enjoyable post-apocalyptic quest through the voice of his flawed, compelling, imminently likeable narrator, Koli. The Trials of Koli, released in September, picks up right where Book 1 left off, with Koli and his companions traveling across an ecologically transformed England in the wake of civilization to find the source of a signal that might mean a semblance of technology and government remaining in London.

Of course, a quest is only as good as those you travel with, and in this Koli is fortunate. Besides the traveling medicine woman Ursula, who carries some of the country’s last viable medical technology, and the sentient Dreamsleeve Mono, an advanced music player that has become Koli’s closest friend, the character who shines in this volume is Cup, a vagabond picked up as captive after a tussle with a cannibalistic cult at the end of the first volume. Cup becomes an ally and companion in this second volume, and with her character Carey is able to explore what life might be like for “crossed,” or transgendered, individuals in this new world.

Besides navigating the spectrum of hatred to acceptance that Cup elicits as they travel through various villages, Cup’s identity provides a point of conflict within the company. Ursula, with her access to medical technology, must decide if it’s ethical to give Cup the hormone-blocking treatment she wants to postpone the onset of puberty, even though the therapy for full gender transition is no longer available. This conflict isn’t a major plot point, but it’s integral to the heroes’ journey and a nuanced depiction of a transgendered character. Of course, at the same time our heroes are navigating this they’re also figuring out how to deal with the coming seed-fall of a forest full of carnivorous trees.